Counterterrorism yearbook 2019: China

China’s problem with terrorism has until recently been largely isolated to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the far northwest of the country. However, that’s been changing as Uyghur militancy and terrorism increasingly impinge on Chinese interests in Central Asia, South Asia and the Middle East. China’s response to terrorism is now marked by domestically and internationally oriented postures.

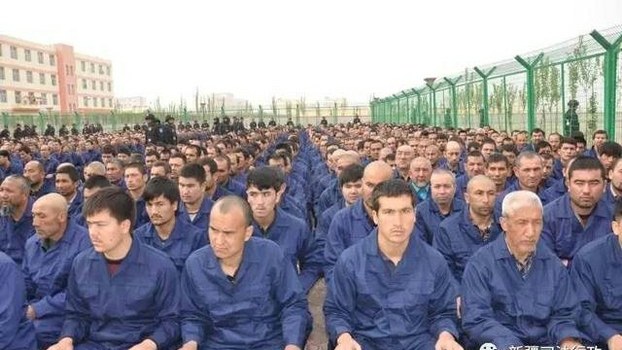

Domestically, Beijing’s explicit framing of Uyghur opposition as directly inspired or supported by externally based militant jihadist organisations has been used to justify the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) implementation of a pervasive security state in Xinjiang and the mass internment of up to a million Uyghurs in ‘re-education’ facilities.

Internationally, the existence of Uyghur militants abroad (particularly in Afghanistan and Syria, fighting under the banner of the al-Qaeda-affiliated Turkestan Islamic Party), combined with President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy agenda, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has ensured that counterterrorism is now a prominent interest in Chinese diplomacy throughout Central Asia, South Asia and the Middle East.

Since 9/11, China has labelled incidents of violence in Xinjiang as the work of the al-Qaeda-aligned (and originally Afghanistan-based) East Turkestan Islamic Movement and Turkestan Islamic Party. However, there’s little evidence that either of those groups ever successfully mounted an attack in Xinjiang.

Nonetheless, a number of high-profile terrorist attacks in or related to Xinjiang in recent years—such as the October 2013 SUV attack in Tiananmen Square and the April 2014 Kunming railway station mass stabbing attack—prompted the CCP to embark on a ‘people’s war against terrorism’ that has resulted in significant changes in the ideological, legal and institutional underpinnings of Chinese counterterrorism policy.

The regional government’s expenditure on public security ballooned in 2017, amounting to approximately US$9.1 billion, a 92% increase on such spending in 2016. Much of the money has been absorbed by the development of a pervasive, hi-tech ‘surveillance state’ in the region. The system includes facial-recognition software and iris scanners at checkpoints, train stations and petrol stations; biometric data-collection for passports; mandatory apps to cleanse smartphones of potentially subversive material; surveillance drones.

Significantly, the system relies not only on technology but also on manpower to monitor, analyse and respond to the data it collects. Its rollout has thus coincided with the recruitment of an estimated 90,000 new public security personnel in the region.

Over the past few years, China has introduced a suite of counterterrorism laws, starting with national legislation in December 2015, followed by legislation for Xinjiang in August 2016 and regulations on ‘de-extremification’ in Xinjiang in March 2017. Much of the legislative agenda has been explicitly framed by the Chinese authorities as constituting a preventive approach akin to that undertaken under the rubric of ‘countering violent extremism’ by a variety of other states to address the causes of terrorism.

Central to that approach is the concept of ‘de-extremification’. According to the Xinjiang regional government’s own March 2017 regulations, ‘extremification’ refers to ‘speech and actions under the influence of extremism, that imbue radical religious ideology, and reject and interfere with normal production and livelihood’ and can include 15 ‘primary expressions’ of ‘extremist thinking’, including wearing beards, headscarves and veils and selecting ‘irregular’ names for Uyghur children.

‘Extremism’ is therefore clearly identified as inherent to everyday markers of Uyghur identity, resulting in the securitisation of ‘all religious behaviours, not just violent ones’.

Uyghurs are now conceived of as an almost biological threat to the health of society. Government officials have described Uyghur ‘terrorism’ as a ‘tumour’ to be eradicated and Islamic observance as akin to drug addiction. The mass detention and ‘re-education’ centres thus emerge as part of the CCP’s ‘cure’ for such pathologies.

As dystopian and disturbing as this is, it’s also now clear that China is seeking to both embed its Xinjiang-centric counterterrorism focus within its diplomatic relations and export the methods and technologies that have underpinned its ‘surveillance state’ in Xinjiang.

Beijing has pushed its counterterrorism agenda in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in Central Asia since its founding in June 2001, focusing the organisation on combating the ‘three evils’ of ‘separatism, terrorism and extremism’. This has included regular ‘anti-terror’ exercises by SCO militaries, intelligence sharing, and closer police and law enforcement cooperation between Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Of particular note have been agreements for the ‘guaranteed extradition’ of individuals on shared ‘blacklists’ in violation of international law.

China is also seeking to target the Uyghur diaspora beyond its borders—including in Australia—with its system of surveillance by creating ‘a global registry of Uighurs who live outside of China, threatening to detain their relatives if they don’t provide personal and identifying information to Chinese police’.

Potentially more far-reaching is the fact that Xi’s multibillion-dollar BRI is intended to invest not only in physical infrastructure, but also in the infrastructure and technology necessary to create a ‘digital Silk Road’. Much of the investment is coming from many of the same tech companies—such as Alibaba, Huawei and ZTE—that have been heavily involved in establishing the surveillance apparatus in Xinjiang. That experience has enabled them to ‘incubate’ and ‘mature within a strict set of Chinese controls and grow profitable before going global’.

Beijing’s focus on the ‘digital Silk Road’ has provided these companies with expansion opportunities in a variety of BRI partner countries as far afield as Zimbabwe, Venezuela, Malaysia and Mongolia.

Ultimately, the evolution of China’s counterterrorism efforts amounts to a cautionary tale in the ‘war on terror’.

China has effectively instrumentalised the threat of Uyghur ‘terrorism’ both within its domestic governance of Xinjiang and in its diplomacy to repress and control Uyghur identity and autonomist aspirations. Its more recent efforts at forging the ‘digital Silk Road’, meanwhile, raise the possibility that the ‘presence of Chinese engineers, managers, and diplomats will reinforce a tendency among developing countries, especially those with authoritarian governments’, to adopt China’s approach of ensuring that technology serves the interests of a homogeneous state.