China–Philippine relations sail on calmer seas—for now

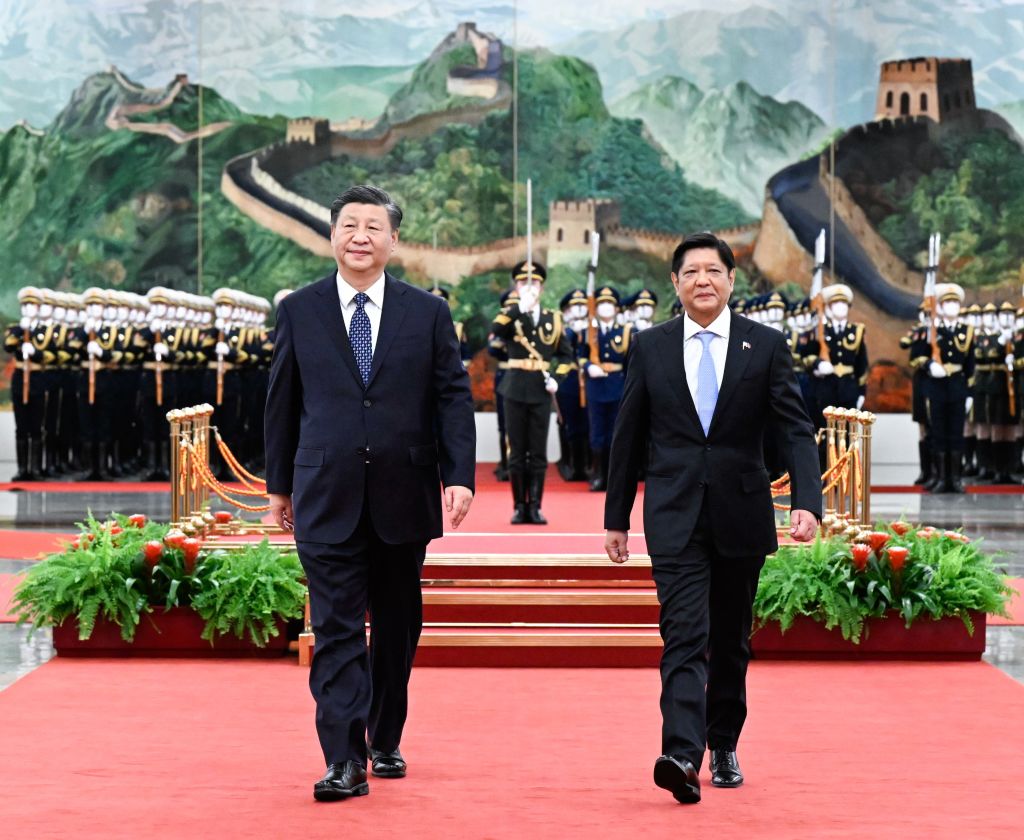

On 4 January, Chinese President Xi Jinping clasped hands with his Philippine counterpart under very different circumstances from the last time he welcomed a Philippine leader to Beijing.

During that September 2019 visit, which Xi hailed as a ‘milestone’, Ferdinand Marcos Jr’s predecessor, Rodrigo Duterte, told a crowd in the Great Hall of the People: ‘I’ve realigned myself in your ideological flow’ and ‘I announce my separation from the United States’.

Almost four years later, China’s incessant bullying and unsafe brinksmanship towards the Philippines and other Southeast Asian nations over rival claims and privileges in the South China Sea have scuttled Duterte’s era of good feelings and drawn Manila even closer to Washington. Before landing in Beijing, Marcos admitted that ‘maritime issues … do not comprise the entirety of our relations’ but emphasised that sabre-rattling in the South China Sea remained a ‘significant concern.’

Practising the art of the geopolitical pivot, Xi largely side-stepped the South China Sea conflict during his meeting with Marcos and doubled down on previous promises of greater economic interdependence. A slew of initiatives emerged from the summit, including joint oil and gas development projects, renewable energy investment, increased trade and a crisis hotline to resolve maritime disputes.

This course correction towards calmer seas underpins Beijing’s decision to rehabilitate relations with Manila and other neighbours by reverting to its old narrative of non-interference and inter-Asian ‘cooperation’. Recent actions and statements, like a pledge that China would never use its military might to ‘bully’ smaller nations, reflect China’s acknowledgment that its decade-long pugnacious campaign to dominate the South China Sea has done more harm than good. By embracing ‘peaceful outcomes’, Beijing seeks to recast itself as a regional force for good, a hegemon that can spread economic growth and ensure Asian affairs are settled by Asian countries—not ‘aggressive’ foreigners like the US.

In doing so, this kinder, gentler China pledges to embrace cooperation, not confrontation, benevolence not belligerence, in pursuit of ‘win–win outcomes’. These outcomes, according to the Global Times, will usher in a ‘new golden age’ in Sino-Philippine relations. But as the saying goes, all that glitters is not gold. If the Marcos administration is committed to upholding its South China Sea claims in the face of Chinese revanchism, it cannot grow too comfortable with Beijing’s ‘cooperation’ approach.

China has pressed its expansive maritime sovereignty claims in the South China Sea since the late 1940s; it wasn’t until the early 2010s that these claims (often unfounded) gained a sharp set of teeth. In accordance with Xi’s ‘national rejuvenation’ goal, Xi-era Chinese military doctrine stresses control of the ‘near seas’, which these sovereignty claims support.

‘Near seas’ control offers manifold benefits. It would enable China to actualise its anti-access/area-denial concept, solidify power projection throughout the first island chain, and raise the counter-intervention risk calculus for Washington and its allies, all while expanding a security buffer zone to protect the mainland. In addition, unrivalled ‘near seas’ (or South China Sea) control legitimises access to vast and untapped natural resources while safeguarding critical sea lines of communication, which China’s leadership believes could be threatened in a conflict with the West.

Yet after a decade of dredging disputed reefs into military bases, forcing sovereignty showdowns, sinking fishing vessels, harassing survey and resupply vessels, and touting its sovereignty over nine-tenths of the South China Sea, China’s ‘sea control’ campaign has come at a steep geostrategic cost.

In Manila alone, the security establishment has mounted a fierce resistance to China’s maritime encroachments, even pressuring Duterte to reverse rapprochement with China and rescind plans to slacken ties with the US military. The same goes for other Southeast Asian nations. According to the 2022 State of Southeast Asia survey report, which gauges Southeast Asian leaders’ temperature on a range of regional policy issues, only 26.8% of respondents trusted China to ‘do the right thing’. Of those respondents who didn’t trust China, half of them attributed it to China using its economic and military power ‘to threaten my country’s interests and sovereignty’. Concurrently, some ASEAN countries have distanced themselves from Beijing by strengthening partnerships within ASEAN and with the Quad alliance. Other states, like Malaysia, have increased their defence budgets to protect their South China Sea territory.

China’s renewed goodwill campaign should not be taken at face value. Cooperation doesn’t mean China will bury its ambitious South China Sea interests. It means China will try pursuing those interests peacefully to quell tensions until it can no longer achieve those interests without reverting to an aggressive posture—just like the last time it swapped ‘win–win’ cooperation for win–lose brinkmanship.

The Philippines will then find itself between a reef and a hard place. China will likely offer savoury economic carrots to Manila. In exchange, it may seek Manila’s tacit approval to militarise Scarborough Reef, remove the embarked marine detachment on Second Thomas Shoal, or permit Chinese hydrocarbon survey and drilling operations in the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone, thus making it neither exclusive nor economically beneficial.

But Chinese control of the South China Sea is not a foregone conclusion, despite what Duterte believed. Beijing has already adjusted its risk calculus when the price of international opprobrium outweighed the benefits of maritime belligerence. The Philippines, ASEAN nations and the Quad alliance can continue imposing and signalling that cost. It will require the usual antidote of hard-power prescriptions: jets, corvettes, patrol boats, littoral craft and missiles.

Holding Chinese warships and activities at risk, however, demands more than just a platform and a weapon. The missile must be capable of striking the target. Quad partners should begin integrating the Philippines (and other willing countries) into parts of the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness to provide improved joint awareness, information-sharing and targeting solutions. Quad leaders should also offer economic programs to counterpoise China’s overtures.

Already, Marcos’s decision this month to grant the US temporary and rotational access to four military bases and resume joint maritime patrols in the South China Sea was a wise one because it will help strengthen the Philippines’ defence capabilities, interoperability with allies and commitment to resisting Beijing’s aggressive maritime behaviour. More of that cooperation and coordination is needed, although Marcos has made it clear that the burgeoning US–Philippine military ties pose no direct threat to China, despite being a direct response to China’s militarisation and disruption of the South China Sea.

For now, Marcos is right to balance China and the West with economic agreements for the former and military pacts with the latter. Frank, clear dialogue can cool tensions. But all parties interested in upholding a rules-based order in the South China Sea must keep fielding an appropriate defence of that order, regardless of what ‘win–win outcomes’ China may promise. Then, and only then, can everybody win.