China expands its island-building strategy into the Pacific

The world knows the Republic of Kiribati as a very low-lying nation in the mid-Pacific that is in danger of inundation as the climate changes and sea levels rise.

Much less is known about its strategic location and the attention now being paid to it by Beijing, which has proposed large-scale dredging to reclaim land from lagoons. The aims are to raise the height of atolls and create land for industrial development, including two major ports. The massive works will likely be carried out by the same fleet of dredgers used by China to build artificial islands in its aggressive expansion into the South China Sea, and will almost certainly cause the same severe destruction of coral reefs in Kiribati.

Australia will ignore this activity at its cost.

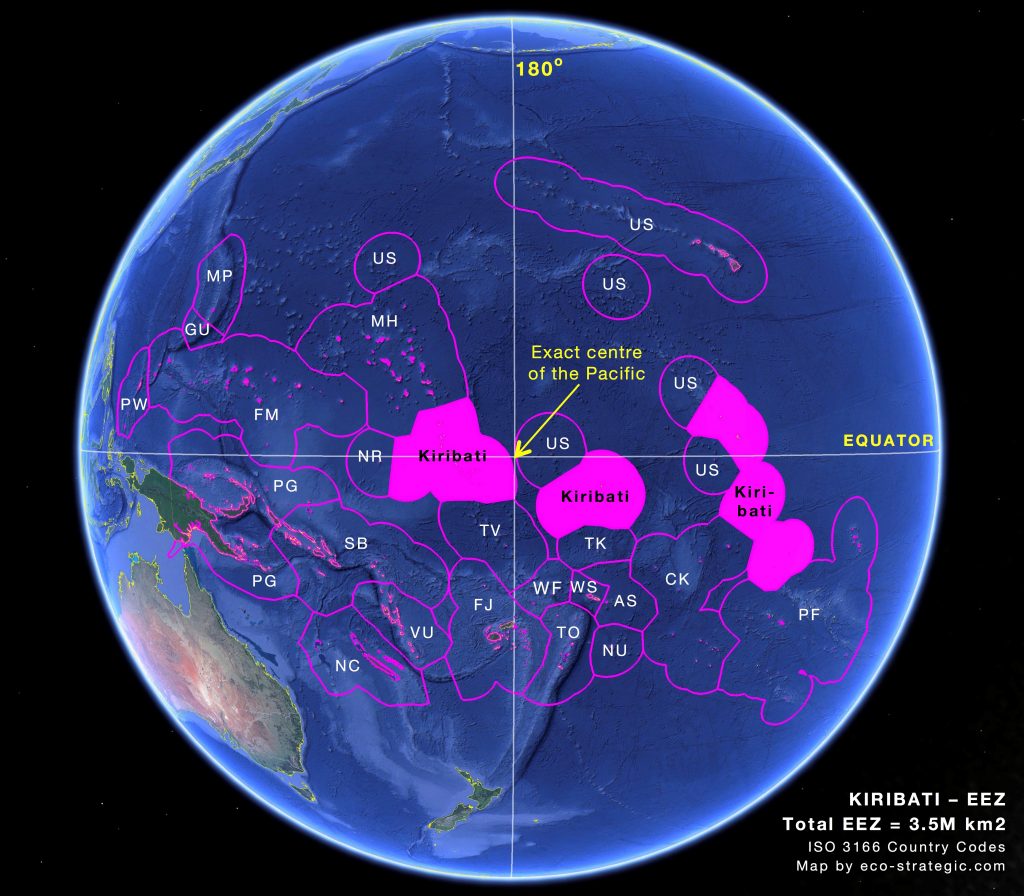

Kiribati lies at the true geographic centre of the vast Pacific Ocean, straddling both the equator and the 180-degree meridian of longitude, and is the only country in the world to span all four hemispheres. Comprising 32 coral atolls and one raised-coral island, Kiribati has three distinct island groups—the Gilbert Islands in the west, the Line Islands in the east and the Phoenix Islands in the middle—with separate exclusive economic zones. The combined EEZ covers 3.5 million square kilometres, about half the size of Australia, and hosts some of the largest remaining potentially sustainable stocks of tuna and other migratory fish, as well as deep seabed minerals. The land area of all the islands combined is only 800 square kilometres and the population is approximately 120,000.

In September 2019, the government of Kiribati switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China, amid accusations of inducements from China. In June this year, the Tobwaan (‘Embrace’) Kiribati Party (TKP) secured a second four-year term in government, amid accusations of election irregularities by all sides.

The TKP’s national development manifesto, the ‘Kiribati 20-year vision’, which looks set to be integrated into China’s Belt and Road Initiative, gives highest priority to building two ‘transhipment hubs’—major ports in a tiny country that has no economic market for such facilities.

One hub is planned at the capital of Tarawa Atoll in the west, which was the site of the first major amphibious landing by US forces in the push against Japan during World War II. The second is planned at the strategically located Kiritimati (‘Christmas’) Atoll in the east, directly south of Hawaii and the major US bases there.

The atolls of Kiribati have very limited land area and are only a few meters above sea level. Like other low-lying atoll nations, Kiribati is directly threatened by climate-change-induced sea-level rise and other impacts that are already occurring. In addition to the transhipment hubs, the 20-year vision proposes large-scale land reclamation. The stated objective is for commercial and industrial development, and ostensibly to raise the atolls as a climate-change adaptation response.

The proposed major island-building and development of so-called transhipment hubs raise the prospect of Chinese military bases, or, at least initially, potential dual-use facilities, being established right across the centre of the Pacific, stretching along the equator for nearly 3,500 kilometres from Tarawa Atoll to Kiritimati Atoll. China also has a moth-balled satellite tracking station in Kiribati, which may now be reactivated.

These facilities would give China control over the world’s best tuna fishing grounds plus swathes of deep-sea mineral resources, and a presence near the US bases at Hawaii, Kwajalein Atoll, Johnston Atoll and Wake Island. They would also be positioned directly across the major sea lanes between North America and Australia and New Zealand. During World War II, Japan’s attempt to block the same lanes were defeated, starting with the Battle of the Coral Sea and then the taking of Guadalcanal in Solomon Islands. Today, China is moving to achieve control over the vital trans-Pacific sea lines of communication under the guise of assisting with economic development and climate-change adaptation.

The developments in Kiribati are part of a much larger Pacific-wide Chinese strategy. Another permutation of China’s ‘island-grabbing’ in the Pacific is the leasing of the highly strategic Hao Atoll in French Polynesia, ostensibly to develop a $2-billion-plus fish farm in the atoll lagoon, which is large and deep enough to accommodate an entire naval fleet. Hao Atoll was a significant French base in the 1980s and 1990s, used to support nuclear weapons tests on nearby Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls. It has an airfield, built by the French, with a runway long enough to accommodate large, wide-bodied transport aircraft.

Control of the facility at Hao, along with those proposed in Kiribati and elsewhere across the heart of the Pacific, represents a power-projection capability that is orders of magnitude beyond the old ‘three island chains’ construct applied to China by strategists for decades, and requires an urgent realignment of the strategic response.

Vulnerable Pacific island nations and territories are increasingly turning to ‘assistance’ from China because they perceive that their development needs are not being addressed by other partners and that their very real concerns about the existential threat from climate change are largely brushed aside by Australia and the US. Meanwhile, China panders directly to such concerns and bills itself as a global leader on climate change, despite now being the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Australia’s Pacific step-up needs a lot more ‘up’ in its ‘step’ if such developments are to be effectively countered—and if vulnerable nations like Kiribati are to be kept in Australia’s ‘Pacific family’ as promoted by Prime Minister Scott Morrison. For its own national security, Australia needs to more overtly recognise both the climate change and broader development concerns of Pacific island countries, and tailor its development assistance to address these concerns in a much more meaningful and concrete way.