China and India tussle online over vaccine diplomacy

China and India are using the inoculation drive against Covid-19 as part of their diplomatic efforts to shore up global and regional ties—and they aren’t the only ones. But now the two countries are engaged in a tussle playing out online and in the media over the messaging around their respective vaccine candidates, reflecting an emerging flashpoint between the two powers.

Both countries have approached vaccine development and distribution as a matter of national pride. China has a number of candidates, including CoronaVac, made by the pharmaceutical company Sinovac. Another, made by Sinopharm, has been approved for use in China. India’s Serum Institute is manufacturing doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, known locally as Covishield. And Bharat Biotech International and the Indian Council of Medical Research have developed a vaccine known as Covaxin.

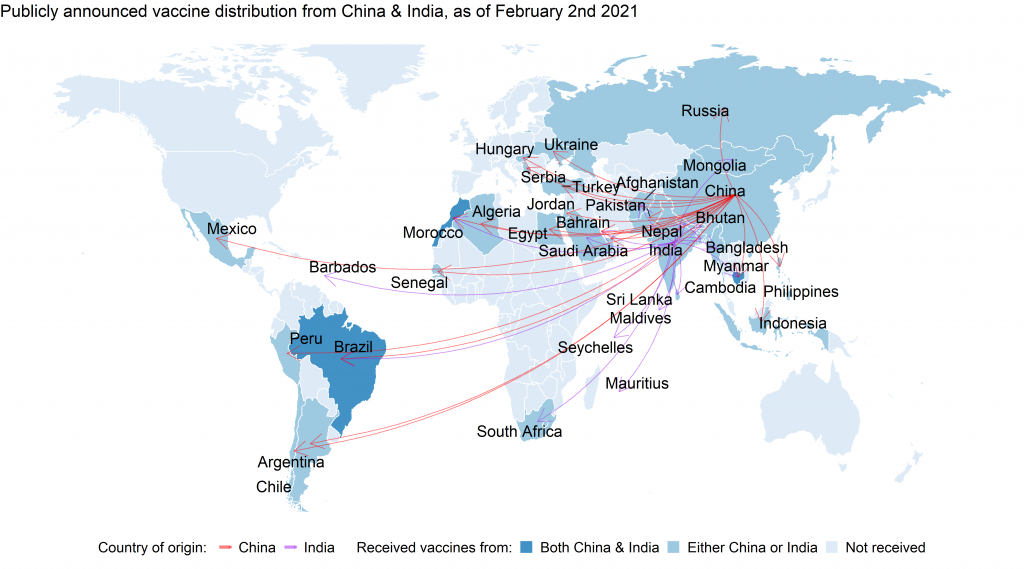

India has a long track record of vaccine manufacture and launched a ‘neighbourhood first’ policy for Covid-19 vaccine distribution, with reported plans to send supplies to Mongolia and Pacific island states as well as Myanmar, Nepal and Sri Lanka. This soft-power initiative has been characterised by some as a bid to counter China’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific and its push to distribute vaccines and medical supplies in the region.

On Twitter, Chinese diplomatic accounts have hailed reports of the arrival of its vaccines in countries like Sri Lanka and Cambodia. China reportedly plans to distribute 10 million coronavirus vaccines overseas as part of the COVAX initiative, primarily in developing nations. Meanwhile, Indian politicians have been using the hashtag #VaccineMaitri—or vaccine ‘friendship’—to celebrate Indian-made vaccines as they head for places like Brazil and Bangladesh. In January, posts using the #VaccineMaitri hashtag attracted at least 541,000 interactions on Facebook, according to the social analytics platform Crowdtangle.

As the global vaccine rollout ramps up, state-linked social media accounts and media outlets in both countries have amplified negative narratives about their competing vaccine candidates. The Chinese Communist Party–linked Global Times, for example, has published more than 20 stories mentioning India and vaccines in January in its English-language edition. Global Times pieces have spotlighted ‘safety and efficacy’ concerns about India’s vaccines, contrasted with a piece about how Indians in China are embracing China’s vaccines. Another said, ‘New Delhi could take note that vaccines should not be a geopolitical tool and vaccine exports is not a contest.’ On 25 January, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Zhao Lijian was asked about India’s ‘vaccine diplomacy’ at a press conference and decried ‘malign competition, let alone the so-called “rivalry”’.

This messaging from Chinese media and officials has set off a war of opinion pieces. The Times of India accused China and the Global Times of starting ‘a smear campaign’ against India’s vaccines. India’s News18 claimed that the Global Times was ‘rattled by New Delhi’s “Vaccine Maitri” initiative’ and that the world sees India ‘as a benevolent friend’. A headline on another Indian television network declared ‘Some Spread Disease, Some Offer Cure’, according to the South China Morning Post, referring to reports that Covid-19 first spread from China—a sentiment echoed by some Indian politicians online.

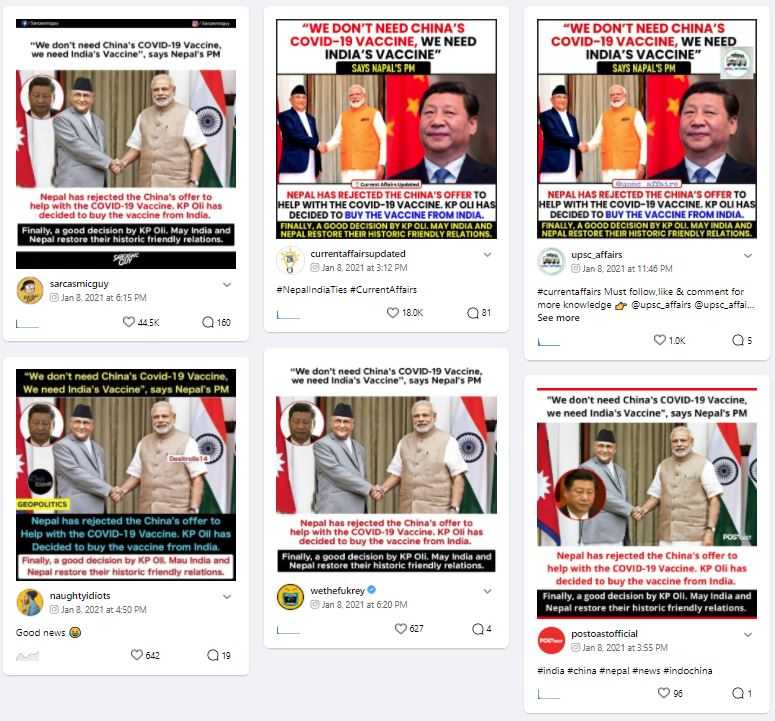

In some cases, tension has emerged over countries in which India and China are competing to provide vaccine access. For example, some Indian news outlets claimed that Nepal ‘preferred’ India’s vaccines over China’s, an idea that was also reflected in a variety of memes on Facebook, including some that included a quote credited to Nepal’s Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli that is unsourced and unverified. The country has long been the focus of geopolitical maneuvering between its two powerful neighbours. Versions of the post also appeared on Instagram, where a sample of six posts received more than 65,000 interactions, according to Crowdtangle.

Another meme that was shared across Facebook, including by a number of Indian political meme accounts that often share pro-government content, sought to amplify negative narratives about other vaccines, contrasting them to those made in India. The meme highlighted the supposed link between recent deaths in Norway and the Pfizer vaccine—a narrative that’s also been used this year by Russian and Chinese government-linked accounts—despite no definitive evidence of cause and effect.

The Cambodian government, which typically has close ties with China, reportedly requested doses of India’s vaccines. After a speech on Cambodia’s Covid-19 response from Prime Minister Hun Sen that was interpreted by some news outlets as a rejection of China’s vaccines, the claim was strongly rebutted by China-linked social accounts. Tweets from a reporter for Chinese state media about the issue were retweeted by foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian. CCP diplomatic accounts later celebrated the arrival of China’s vaccine in the country.

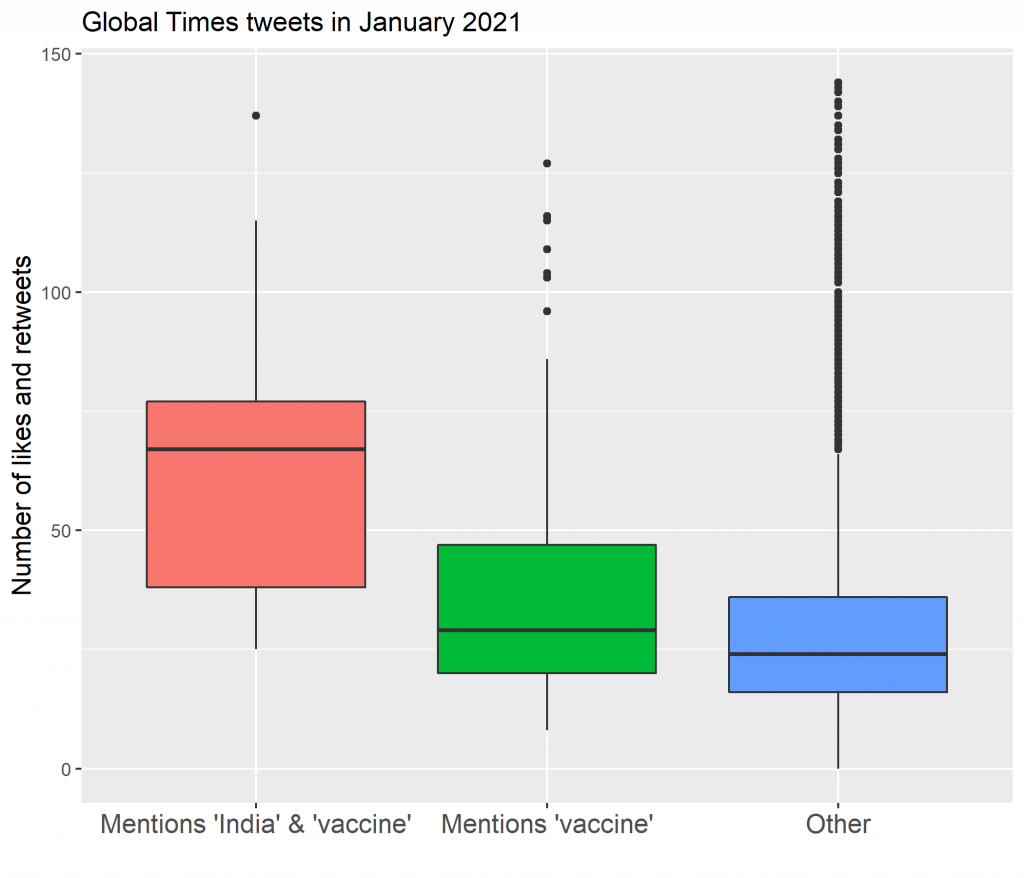

In response to Global Times articles about India’s vaccine drive, pro-Indian netizens have dominated the comments sections of the outlet’s social media posts. On Twitter, an analysis of 3,200 Global Times tweets in January found that those mentioning ‘India’ and ‘vaccine’ had on average more likes and retweets than those on other topics. Many of these retweets were ‘quotes’ where pro-India accounts retweeted Global Times tweets with comments supporting Indian vaccines or criticising Chinese-produced vaccines.

Likewise, articles posted on the Global Times Facebook page have been inundated by pro-Indian accounts boasting about the countries receiving Indian-manufactured vaccines or criticising the efficacy of the Chinese vaccines. One Facebook post by the Global Times that shared a link to a story alleging a ‘rocky road ahead for New Delhi’s vaccine export campaign’ received more than 400 comments, many with a version of the sentiment ‘China made the virus, India made the vaccine’—a phrase also used in some Indian media. ‘You exported the virus. India exporting vaccine’, another said.

Likewise, articles posted on the Global Times Facebook page have been inundated by pro-Indian accounts boasting about the countries receiving Indian-manufactured vaccines or criticising the efficacy of the Chinese vaccines. One Facebook post by the Global Times that shared a link to a story alleging a ‘rocky road ahead for New Delhi’s vaccine export campaign’ received more than 400 comments, many with a version of the sentiment ‘China made the virus, India made the vaccine’—a phrase also used in some Indian media. ‘You exported the virus. India exporting vaccine’, another said.

Tensions between India and China have been ongoing across a variety of fronts, not limited to vaccine distribution. Border skirmishes have continued between the two powers in the Himalayas, including a deadly clash in mid-2020. India has also banned TikTok and other Chinese apps over claims the apps were ‘prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of state and public order’.

Vaccine diplomacy, as well as vaccine nationalism, are likely to continue rising in 2021 as immunisation programs get underway globally. Wealthy countries have secured a significant number of doses and there are fears that poorer nations will be left behind. Medical experts have expressed concern about some Chinese and Indian vaccine candidates, largely over a lack of transparent testing data and the risk of premature approval, respectively. Yet while access to Covid-19 vaccines and transparency about their efficacy and safety are priorities, influence operations that seek to demonise or cause confuse about certain vaccine candidates could complicate such initiatives, creating a risk to public health.