Business as usual in a time of upheaval: the cost of Australia’s defence

The big defence news in Australia this year was in the 2020 defence strategic update released on 1 July. The update and its accompanying force structure plan ended speculation about the defence budget and reaffirmed the government’s commitment to the robust funding line presented in the 2016 defence white paper. It also extended that funding line for a further four years.

The 2020–21 budget released on 6 October delivers the funding promised by the government in the update and, indeed, before that in the 2016 white paper. Despite the pandemic, the defence budget grows by around 9% this year, to $42.7 billion. At 2.19% of GDP (based on the budget papers’ prediction of GDP), that easily meets the government’s commitment to spend 2% of GDP on defence by 2020–21. For those who might suggest that that occurred only because GDP fell, defence funding would still have reached 2% in a hypothetical economy that hadn’t been hit by a pandemic.

As I explain in ASPI’s new budget brief, Defence’s budget statements are consistent with the white paper and the update in funnelling much of the increased funding into the capital budget. Over the longer term, capital acquisitions grow to 40% of the total budget; this year, they reach 34%.

While that funding is necessary to deliver the new capabilities that the update assesses are needed to meet our strategic circumstances (such as long-range strike and area-denial capabilities), the growth rate presents risks for Defence. When we combine the overall budget growth, capital’s growing share of the total budget and the government’s clear expectation that Australian industry will get a big share of that money, then it becomes apparent that the amount spent on local equipment will need to grow from around $2.6 billion last year to $10 billion a year by the end of the decade.

The 2020–21 defence budget shows that the challenges for the capital program aren’t off in the distance—they’re immediate. The total capital budget is projected to grow by over $3 billion to $14.3 billion this year, or by 27.4%. It’s followed by growth of 17.7% and 11.7% in subsequent years. Considering that the capital program has averaged only around 5% annual growth since 2016, achieving that surge will be difficult, particularly with global supply chains disrupted by the pandemic.

As the defence budget grows well beyond 2% of GDP, Defence will need to demonstrate to the government that it can spend it, both to deliver necessary military capability and to stimulate local industry. If Defence can’t spend it, it risks losing it in an age of surging deficits and debt.

Workforce spending increases moderately but continues its decline as a share of the total, down to 31% this year, and is projected to reach 26% by the second half of the decade. The update says that the government will consider increases to workforce numbers next year (the funding for those people is already built into the update’s funding model). Substantial numbers could be needed to operate the future force being delivered by the hefty increases in acquisition spending, but getting there will take time. In the four years since the 2016 white paper, Defence has managed to grow its uniformed workforce by only 1,000. It’s still well short of the white paper’s target, let alone any planned but as yet unannounced increases.

While successive governments have consciously reduced Defence’s civilian workforce, the amount of work needed to deliver and sustain the force has increased. Consequently, Defence’s external workforce of consultants, contractors and outsourced service providers is now its second biggest ‘service’ at 28,632 people.

Moreover, because Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group has been hardest hit by the reductions (losing nearly 40% of its civilians), it has increasingly turned to industry to provide ‘above the line’ project management and professional services traditionally delivered in house.

Analysis of AusTender suggests that Defence signed nearly 2,000 professional services contracts valued at over $2 billion in 2019–20. The four major service providers that CASG is partnering with to provide above-the-line management services have also secured substantial contracts. With only moderate growth in public servant numbers forecast as the acquisition budget grows dramatically, it appears inevitable that Defence’s reliance on its external workforce will continue to grow.

The sustainment budget stays relatively steady as a share of the total, but the systems that Defence is planning to acquire will come with very large sustainment costs. Some of those increases, such as for frigates and submarines, are still a long way off, but others are here now. The F-35/Super Hornet/Growler air combat force is costing many times more than the legacy fleet. Granted, we have only a few data points for the F-35, but achieving an operating cost similar to those of legacy aircraft isn’t looking feasible.

Despite the 2020 update’s assessments of our strategic circumstances and its conclusion that we need new offensive capabilities to impose cost and risk on a potential major-power adversary, and that we won’t have 10 years of warning time to acquire those capabilities, the force structure plan that accompanied the update still has a business-as-usual look to it. That continues in the portfolio budget statements.

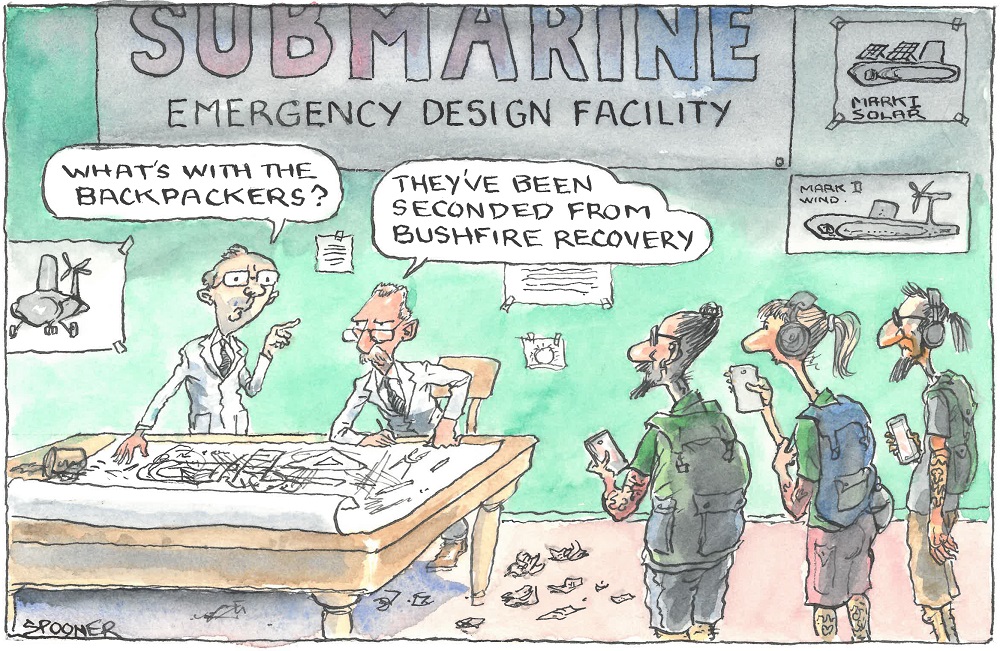

Spending on the naval shipbuilding plan continues to ramp up and is forecast to reach nearly $2 billion this year, even though we’re still two years from the start of construction of the future frigates and three years from the start for the submarines. That $2 billion has a lot further to climb, but there’s no sign that the sense of urgency in the 2020 update has flowed through to project schedules. With the third air warfare destroyer now delivered, the navy doesn’t get another combat vessel to sea for 10 years under the force structure plan. There’s nothing in the budget statements to suggest that that’s changed. It’s a remarkably slow return on the government’s $575 billion investment in Defence. Compared to the spending on acquiring manned platforms, the navy’s spending on autonomous and unmanned systems is virtually invisible in the budget.

Land capabilities also seem to be following a business-as-usual approach. That approach is delivering a range of substantial capability enhancements in digital systems and protected vehicles. However, if the increase in the budget for the army’s future infantry fighting vehicles from $10–15 billion to $18.1–27.1 billion (or around $50 million per vehicle)—while the threat posed by guided weapons delivered by drones, manned aircraft and ground forces proliferates rapidly—doesn’t make Defence reconsider its plan, one wonders what will. It’s time for the government to call for a timeout.

The business-as-usual approach can also be seen in Defence’s management of underperforming helicopters. After stating for many years that it would make the Tiger armed reconnaissance helicopter work, and then telling parliament it was working, Defence appears to have lost patience with the aircraft due to its high cost and low availability. That’s understandable, but rushing to replace it with another manned helicopter is a high-risk move in the light of the vulnerabilities inherent in helicopters. The sunk-cost fallacy has also kept Defence from replacing another chronic underperformer, the MRH-90 utility helicopter. Incredibly, it’s Defence’s fourth most expensive capability to sustain. Between the two, Defence is spending $460 million this year to sustain them.

So there’s plenty of money coming into Defence, but there’s also plenty of room for Defence to do business differently, to get better value for money, to deliver faster and to demonstrate to the government that it can provide the military capabilities that align with the government’s strategic assessments.