Biden’s trade policy U-turn bodes ill for Indo-Pacific security

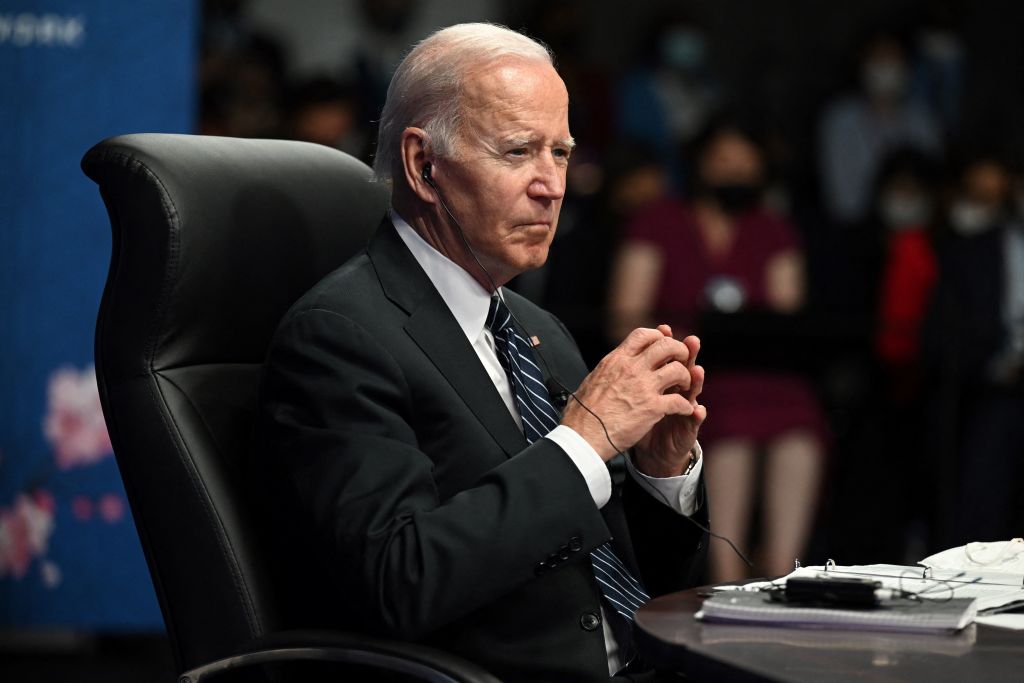

America’s economic isolationism is increasingly entrenched, with President Joe Biden’s administration no longer supporting the trade policies advocated by US multinational corporations, retreating instead to a nativist protectionism.

Creating the conditions for the global expansion of US multinationals had been at the heart of US international economic and political strategy since the end of World War II.

The Biden administration’s U-turn last month on digital trade policy was a shock both to the US business community and to the nations that had been negotiating digital trade agreements with the US on the basis of its long-established position of lowering the barriers to digital commerce.

The US government last month walked away from the digital trade negotiations of both the World Trade Organization and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). Both had been pursuing agreements that would have prohibited all restrictions to the flow of data across borders, the forced disclosure of source codes and algorithms, and requirements to establish local data centres.

Australia, Japan and Singapore all supported these measures, accepting US arguments that lowering the barriers to e-commerce would foster its growth to everyone’s benefit and were left stranded by the US about-face.

The New York Times cited the secretary general of the International Chamber of Commerce, John Denton, saying: ‘The term we would use is “gobsmacked”. We don’t understand what is going on.’

The Biden administration was influenced by Democrats in Congress who believed the measures gave too much power to the technology giants. The US government wants to reserve its own right to regulate these companies and their data flows.

As well as abandoning its negotiations on IPEF’s digital commerce agreement, the administration decided it wouldn’t proceed with the broader IPEF trade discussions after Democrats complained that it didn’t include enforceable labour and environment provisions.

IPEF was a Biden administration creation, designed to fill the policy vacuum left by the Trump administration’s decision to walk away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership free-trade agreement in 2016.

IPEF was intended to be a new kind of international policy framework, setting standards for cooperation among countries on the environment, tax and transparency, supply chains and trade. The US attracted 13 Indo-Pacific nations to sign up to it.

It was explicit at the outset that the agreement wouldn’t provide members with improved access to the US market, which would have required unattainable congressional approval. Instead, the trade section was to cover trade facilitation, labour standards, regulatory practices, agriculture and the digital economy. In the US, it was to be implemented by executive order, rather than by legislation.

Australia and Japan had hoped that agreement on these issues might be a bridge to get the US to join the TPP’s successor, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. Instead, the Biden administration’s decision to walk away from the trade discussions it had initiated repeats the experience of the TPP, on which Asia–Pacific nations spent years arduously negotiating with the US only to have it abandon the venture at the 11th hour.

Donald Trump has made it clear that the remnants of the IPEF agreement, which he said was worse for the US economy than the TPP, wouldn’t survive if his bid to regain the presidency in 2024 succeeded.

‘It’s worse than the first one, threatening to pulverize farmers and manufacturers with another massive globalist monstrosity designed to turbocharge outsourcing to Asia,’ he said.

The US Business Roundtable, which is the peak business lobby group, criticised the decision to abandon the IPEF trade negotiations, as well as the broader policy reversal on digital trade rules.

‘High-standard free trade agreements are vital to advancing the interests of American businesses, farmers, ranchers and workers abroad,’ it said, adding that the decision to abandon negotiations on digital trade ceded leadership over the framing of digital trade rules to competitors (meaning China) and undermined economic and national security interests.

The TPP, which was designed by the Obama administration to cement the place of US business in the Asia–Pacific region, to the exclusion of China, was, like the IPEF digital trade negotiation, framed with the interests of US multinationals to the forefront.

There were challenging discussions over the extension of pharmaceutical patent protection—at one stage the US was pressing for big changes to Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme—and over protection for the US media and entertainment industries. The CPTPP, which was signed in 2018 by all the original members of the TPP except the US, removed those provisions.

With both IPEF and the TPP, agreements that unambiguously favoured US multinationals were abandoned in the face of opposition in Congress from both Democrats and Republicans. It is a long way from 1953, when the president of General Motors, Charles Wilson, was able to tell Congress: ‘What was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa. The difference did not exist. Our company is too big. It goes with the welfare of the country.’

The change reflects a view that while trade liberalisation may indeed have benefited US multinationals, it came at a cost of US domestic manufacturing and the communities that depended on it. Trump’s election to the presidency in 2016 represented a political backlash against the brand of globalisation that had been championed by US multinationals. Biden defeated Trump in 2020 partly by appealing to manufacturing workers in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin.

The rejection of trade agreements is consistent with the US decision to sabotage the World Trade Organization’s appeals tribunal by vetoing all new members until it lost its quorum; its use of national security provisions to impose punitive tariffs on steel and aluminium imports, including from the European Union and Japan; and its retention of the Trump administration’s steep tariffs on Chinese goods.

Instead, the big pieces of economic legislation under the Biden administration have been the Inflation Reduction Act, which, among other things, pours US$370 billion into domestic clean-energy subsidies, and the CHIPS and Science Act, which funnels US$280 billion to domestic microchip research and manufacturing. ‘When the federal government spends taxpayers’ dollars, we’re going to buy American: American products made in America, including American component parts,’ Biden said.

For Australia, 90% of whose exports and 80% of whose imports are traded with Asia, the US’s inward turn is not an immediate economic threat but, as critics charge, it opens the way for China to assert its role as the principal economic partner for the nations of Asia and the Pacific.

Perhaps more fundamentally, it raises a question about the US’s strategic commitment to the Asia Pacific region. The TPP was to have been the centrepiece of President Barack Obama’s ‘pivot’ to Asia, which was to include both a strengthening of US economic influence in the region and a greater military presence. IPEF was the TPP’s pale shadow. If the US no longer places a priority on advancing the interests of US business in the Asia–Pacific, will it see the need to continue underwriting the region’s security?