Battery manufacturing a bad bet for Australia, says Productivity Commission

Great opportunities await the Australian critical minerals industry, according to the Productivity Commission, but it says they are unlikely to include manufacture of end products such as batteries.

The commission’s critique of the emerging industry policy in Australia comes as global technology giants such as Tesla are underwriting Australian critical minerals projects with guaranteed sales.

The commission’s annual review of industry and trade assistance says Australia stands to be a huge beneficiary of the incentives under the US Inflation Reduction Act for sourcing critical minerals either domestically or from free-trade partners.

‘This is apparent in the case of the tax credits for EV purchases by US consumers, where eligibility for the maximum $7,500 tax credit is contingent on at least 40% of the critical minerals used in the EV battery being sourced from the United States, or from US FTA partners like Australia,’ the commission says.

‘These gains would be compounded by United States Congressional approval of designating Australia as a “domestic source” under the US Defence Production Act, thereby providing preferential access for Australia to the US market.’

The US subsidies helped to promote more than US$200 billion in manufacturing projects in the clean-technology and semiconductor sectors last year, double the level of 2021 and 20 times the level of 2019. A study by the Financial Times shows there were four projects worth at least $1 billion each in those sectors in 2019, but 31 that size in August 2022.

According to the Productivity Commission, economic theory says the enlargement of manufacturing in the US and European Union will draw resources away from their services sectors, opening opportunities for Australian exporters of resources and services. Australian manufactured exports will fall, but the commission dismisses that as an issue, saying: ‘[T]he fact that manufactured goods constitute less than 7% of Australian exports by type limits this potential effect.’

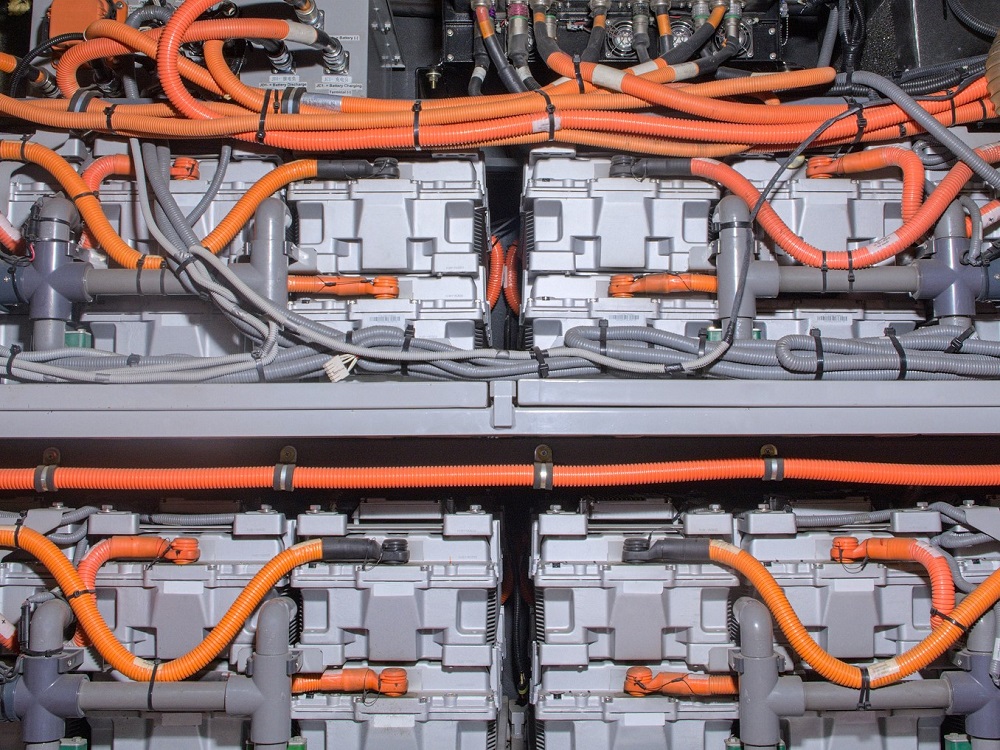

The commission contends that downstream value-adding in Australia will be limited to basic processing of raw materials, with little prospect of establishing significant industries in end products such as batteries:

The presence of critical minerals mining in Australia suggests that there might be a cost advantage for processing in Australia, because (for many of these minerals) large volumes of earth need to be processed to generate small quantities of processed minerals. However, to the extent that these critical minerals are low-volume once processed and refined, and thereby low-cost to transport, a domestic processing capacity is unlikely to create an appreciable cost advantage for a domestic battery industry. That is, the comparative advantage in resource extraction presented by Australia’s resource endowments is more suggestive of a comparative advantage in the processing of low concentration minerals than in final battery production …

[T]he Inflation Reduction Act incentives make it much more likely that a battery industry will rapidly develop and grow in the US, possibly with clustering effects. Such a development would reduce the likelihood that Australia develops an economically efficient battery industry and raises the likelihood that its resources earn better returns in other industries (such as services). And if the Australian Government were to support such an industry, the cost of that support may outweigh the benefits for GDP and economic growth. It may also entrench an inefficient industry that relies on lobbying for more support to sustain itself over time, rather than on relying on its inherent economic advantages.

The Productivity Commission’s scepticism is at odds with the government’s aspirations to capitalise on Australia’s strengths in mining to move downstream through processing to the manufacture of batteries and electric vehicles.

‘[L]everaging our competitive advantages, the critical minerals we mine and refine here, can help us move up the value chain and into downstream processing, helping to create new opportunities and high-paying jobs across Australia, including in our regions,’ Resources Minister Madeleine King said when launching the consultation that led to the formulation of the government’s critical minerals strategy.

The skyrocketing demand for critical minerals will propel the industry’s rapid growth. The International Energy Agency’s new report on critical minerals shows that, over the past five years, the global market for critical minerals, including copper, nickel, lithium, cobalt, graphite and rare-earth elements, doubled, reaching US$320 billion. Demand for lithium tripled, while cobalt sales jumped by 80% and nickel 30%.

The IEA highlights the steps that major consumers are taking to secure their supplies. Seven of the top 10 electric-vehicle manufacturers have signed long-term offtake agreements for lithium and/or nickel projects and many are taking direct equity stakes. Battery makers are pursuing similar strategies, with six of the top seven committing to offtake agreements or equity investments.

For years, the large majority of Australia’s critical minerals prospects have been starved of development funds because they couldn’t secure offtake agreements. That’s now turning around.

Tesla has a major contract with Australia’s Liontown Resources to secure lithium concentrate starting at 100,000 tonnes in 2024 and rising to 150,000 tonnes thereafter. BMW has a deal with the US-based Livent to source lithium in Australia. The South Korean battery maker SK On has invested in Australia’s Lake Resources with rights to up to 230,000 tonnes for 10 years.

Chinese firms are doing the same. A major shareholder in CATL—the world’s biggest battery maker—has made a US$3.7 billion investment in a minority stake in CMOC, the second largest cobalt producer in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. CATL is also leading a consortium to invest more than US$1 billion in developing lithium reserves in Bolivia.