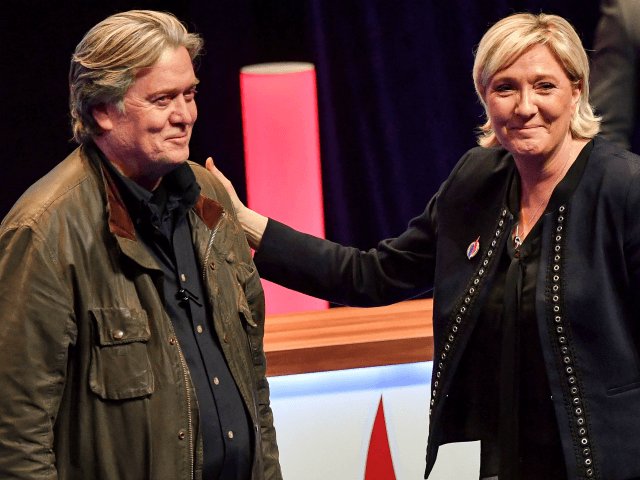

Bannon in Lille

In 1965, Henry Kissinger wrote a book called The troubled partnership, in which he examined the tensions affecting the transatlantic alliance during the Cold War. A stable international order, he argued, demanded the leadership of the United States—a powerful model for democracy in the world—supported by strong ties with Europe. Kissinger probably never would have imagined that, less than six decades later, the US would be playing precisely the opposite role, as a new, darker version of the transatlantic alliance emerges.

Consider last week’s convention of France’s far-right National Front. Upon being re-elected leader of the party, Marine Le Pen announced that it was to be renamed Rassemblement National (National Rally). The guest of honour at this consequential event was none other than Donald Trump’s former chief strategist, Stephen Bannon.

‘All great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice,’ Karl Marx famously wrote, ‘the first time as tragedy, second as farce.’ It would be easy to place the convention in Lille in the ‘farce’ category. After all, Le Pen and Bannon are both political rejects.

Le Pen lost last year’s French presidential election to Emmanuel Macron in a landslide. Moreover, she is now being challenged within her own party by her much younger and more intellectually impressive niece, Marion Maréchal‑Le Pen, who spoke just ahead of US Vice President Mike Pence at February’s Conservative Political Action Committee gathering in Washington, DC.

As for Bannon, he was fired unceremoniously by Trump in August 2017. To add insult to injury, Trump released a statement declaring that Bannon ‘had very little to do’ with Trump’s victory in the presidential election, and had lost not just his job, but also ‘his mind’ when fired.

Bannon’s presence at the Lille event was paradoxical. After all, his firing was rooted partly in his extremism, while Le Pen is currently attempting to widen her party’s support by softening its image. Yet, in another sense, his participation made perfect sense, as it reflected the ongoing development of a transatlantic populist alliance, a bleak variation on the ‘geography of values’ upon which the Cold War alliance was based.

Despite Bannon’s own political setbacks, he maintains that the ‘tide of history’ is irresistibly moving toward the populists. From his perspective, with Trump having secured the US presidency—a development that has destabilised the world order that Bannon and his ilk so badly want to burn down—it is only a matter of time before Europe follows in America’s footsteps.

It would be dangerous to dismiss Bannon’s vision as mere bluster. Macron may have won the day in France, but Trump’s electoral victory was no accident. Nor was the strong showing by populist parties in this month’s election in Italy, where the anti-immigration League party and the anti-establishment Five Star Movement together secured some 50% of the vote.

Even Germany has, to some extent, fallen victim to populist forces. To be sure, a new grand coalition government—comprising Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union, its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union, and the Social Democratic Party—has been formed. But it took more than five months for the parties to agree, and the largest opposition party is now the far-right Alternative for Germany. In a country that seemed to have been vaccinated against populism by its Nazi history, this is a particularly distressing development. Democracy is more fragile than it may seem, and it can never be taken for granted.

So how can we stem the populist tide? For starters, political elites on both sides of the Atlantic who still believe in liberal democracy must recognise that it is they who are responsible for populism’s rise, owing to their failure to respond adequately to the concerns of the electorate. They must work tirelessly to find real solutions to the problems, from inequality to migration, that have fuelled support for populist forces. Those solutions must address not only technical challenges, but also citizens’ feelings—skilfully tapped by populists—of disenfranchisement and loss of identity.

Of course, US Democrats must also find a compelling candidate to run against Trump in the 2020 presidential election. And France and Germany must push forward with further European integration. Here, France has a special responsibility, under Macron’s leadership.

And, make no mistake: contrary to what Bannon said in Lille, it is Macron—not Le Pen and her rebranded party—who holds the key to the future of democracy in France. If he fails to make the system work for more of the electorate, France could well go the way of the US, setting a dangerous precedent for the rest of Europe. In such a scenario, the transatlantic alliance really would be in deep trouble—and so would the world order that it underpins.