Australian views on the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework

The deterioration in the global economic outlook in the face of multiple crises—including rising inflation, the war in Ukraine and autocratic belligerence, along with the requirement for urgent action to address the systemic threat of climate change—has heightened Australia’s concerns about economic security in the Indo-Pacific.

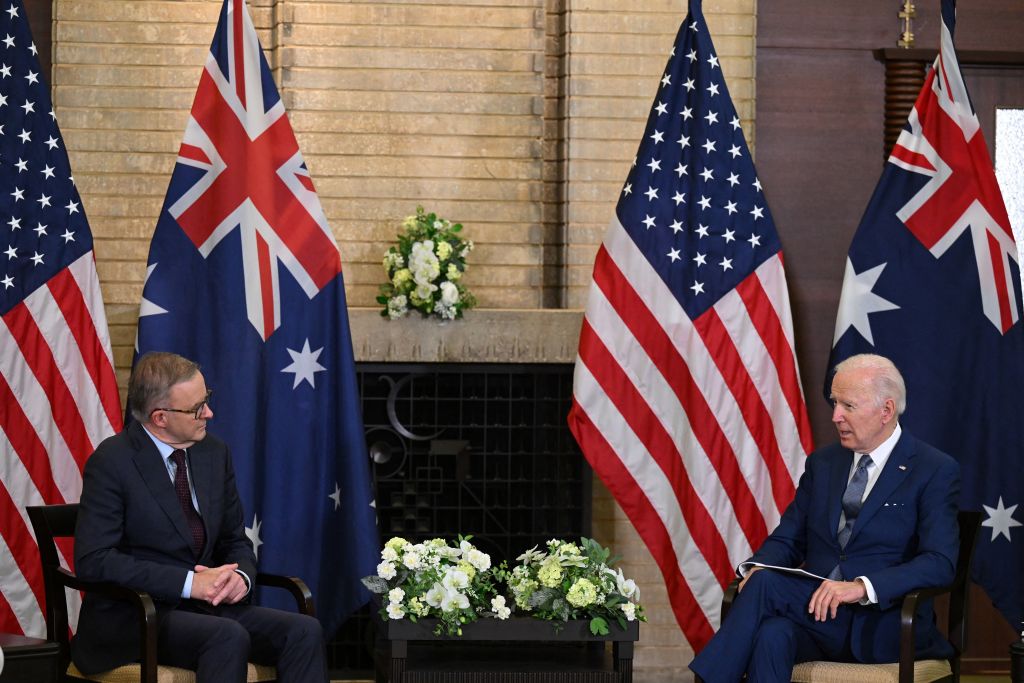

To coincide with the launch of ASPI’s office in Washington DC, we undertook a short research project to get a sense of how Australian policymakers view the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), announced by President Joe Biden in May. IPEF takes its place among the Indo-Pacific’s already crowded field of regional mechanisms.

Australian officials surveyed for our report said they the IPEF as an opportunity to bring more investment into the region, shape standards setting, form collective solutions to supply-chain risks, and influence the direction of clean energy infrastructure. They view it as a potentially innovative way to boost regional investment rather than as a mechanism to strengthen the usual substance of trade agreements, such as market access into the US.

Understanding the offer is crucial to understanding the IPEF. In the conventional terms of trade agreements (offers and requests), the IPEF has been criticised as failing on multiple fronts. For some trade analysts, it extends insufficient offers, in the form of market access, in exchange for onerous demands on participant countries to conform with expectations on standards for green-technology and digital-economy initiatives.

But, as Australian officials have pointed out, the IPEF isn’t a trade agreement. Rather than seeking to influence behaviour by negotiating the regulatory terms of market access, the framework relies on inward investment into the region—if certain behavioural conditions are met—as an alternative to market access. The behavioural conditions across the IPEF’s four policy pillars—supply-chain resilience; clean energy and decarbonisation; tax and anticorruption; and trade—are yet to be negotiated, which is seen as a distinct opportunity for Australian decision-makers to build regional capacity.

Australian trade ministers have for some years made routine statements about trade expansion and diversification. In the lead-up to the federal election in May, Labor Party representatives said they were committed to diversifying trade and taking a more expansive and proactive approach to regional engagement.

The newly elected Labor government is looking to connect trade with building the local Australian industrial base through public and private partnerships such as the National Reconstruction Fund. There’s a varied mix in the priority areas indicated by the government, which include multibillion-dollar initiatives to invest in green metals (steel, alumina and aluminium), clean energy component manufacturing, medical manufacturing, critical technology, advanced manufacturing, agriculture and fisheries.

It will be essential in the early development of the IPEF to move beyond broad statements towards action on key issues of concern, like supply-chain resilience, international technology standards, and tech cooperation on the green economy. This is particularly important if the framework is to deliver results outside existing regional economic agreements, such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, which Australia is a party to but the United States is not.

Our analysis was informed by interviews with officials from across the Australian government and in industry bodies with portfolios that are relevant to the IPEF’s four pillars. While we note that the officials interviewed aren’t the ultimate decision-makers and that there’s a new government in Canberra with its own emerging priorities, our report offers insights into the potential opportunities for Australia to shape the framework.

As participating nations look towards beginning negotiations within IPEF’s pillars, we offer the following recommendations.

The US, as the convener of the IPEF, should lean into Australia’s capacity-building expertise in the region. Australia has a long history of organising capacity-building and training exercises in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. Examples potentially relevant to the IPEF include the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific. Future engagement should be based on an objective assessment of the efficacy of past and existing programs, with a clear eye on enhancing coordination and adding value to avoid fruitless duplication. Focusing capacity-building on ensuring that participant countries have the skill sets required to engage effectively in the IPEF in each pillar area will create a sense of joint mission.

Participant countries should quickly begin organising dialogues on the pillars involving relevant government agencies and non-government organisations, such as peak standards bodies. To strengthen the IPEF’s relevance, it’s important to ensure that governments are open to understanding the different perspectives on each of the four pillars among nations and between the public and private sectors. With the IPEF still in its early stages, it’s fundamental for officials to create specific mechanisms focused on each of the four pillars to allow participating nations to underline their key interests and their visions for the IPEF.

Participating nations and their corporate sectors should work together to identify areas of vulnerability and criticality in regional supply chains. Akin to the supply-chain initiatives that Australia has with the UK, Japan and India, new intergovernmental and government–industry forums can be established through the IPEF. The overall intention is to build avenues for cooperation among like-minded nations.

Mechanisms for enhancing capital flows between IPEF partners should be investigated. If the key strength of the IPEF is that it provides opportunities for increased investment in the region, then strategies to enhance the relations of official bilateral donors and creditors and private-sector involvement need to be followed. Some minilateral initiatives, such as the US–Australia–Japan Blue Dot Network and the G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, already aim to boost foreign investment, so the IPEF should study and, where possible, complement those initiatives.