Australia needs drug testing and opioid blockers to reduce overdose deaths

In late 2019 I wrote an article about the growing problem of overdose deaths in Australia that has, sadly, continued to plague the country. In the most recent Penington Institute ‘overdose report’, we see that 2,070 people died from drug overdoses in 2018. That number has been growing and will continue to rise unless action is taken. And a greater proportion of overdose deaths are being caused by opioids, both prescription and non-prescription. The report shows that 1,556 of those deaths were identified as being unintentional. More recently, a report on drug trends released in April by the University of NSW’s National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre shows that the trend continued into 2019, with 1,865 overdose deaths, 61% of which were from opioids.

Australia is obviously not immune to the problems faced by other nations when it comes to addictions and drug abuse. The rampant opioid problem worldwide has been gaining ground in Australia and combined with the continuing use and abuse of other drugs like crystal methamphetamine, or ‘ice’, has gained a firm foothold. Recent reporting on Australian drug trends by the US-based Addictions Center describes a steadily increasing use of prescription opioids. Doctors currently write approximately 14 million prescriptions for opioids annually, which is of concern because 10% of those prescribed with them will become addicted. When we consider the concurrent continuing abuse of ice, the country is in crisis when it comes to managing drug addiction and the subsequent overdose problem.

The reaction, or perhaps non-reaction, to the growing drug problem should concern Australians as much as the problem itself. Foundation 61, a not-for-profit addictions facility in Geelong, states that the wait list for residential drug treatment has grown to new highs, with clients waiting 6 to 12 months on its waiting list for treatment, which now numbers 5,000 people in Victoria alone. The Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association, another treatment program option, advises that there are 2,500 people on its waitlist. Those sorts of examples are not unique to Victoria, and it’s clear that they’re not anomalies. Drug abuse has been growing across the country, perhaps even faster during the Covid-19 pandemic. But the ability to manage addictions has not grown. Fast and easy access to treatment is only possible for patients with approximately $30,000 available to pay for a private facility.

A recent report by Victorian Coroner Paresa Spanos into the tragic death of five men over a six month period, after ingesting what they believed to be ‘MDMA and/or magic mushrooms’, identified changes she believed were necessary for public safety. Her recommendations included an early warning system to flag indications of increased harm as a result of street drugs and a system in which users could have their drugs tested prior to use. The coroner observed that more must be done by those who have a duty of care, given the growing illegal drug market that includes drugs that are killing increasingly often.

As drug abuse trends continue to shift, there are serious impacts on the health and safety of those involved. Some may argue that drug abusers have made personal life decisions and that they ought to expect bad things to happen to them, but the stark reality is that after 40 years in public service, including 32 years in policing, I know that no family, community, culture, socio-economic group or individual is safe from addiction. We have a responsibility as a society to focus on doing what we can to save lives, including those of drug abusers and addicts. I argue that we have a duty of care to all of our fellow citizens, drug abusers or not. I agree with Spanos that more must be done to reduce the harm if it is within our capability to do so—and I would argue that it is.

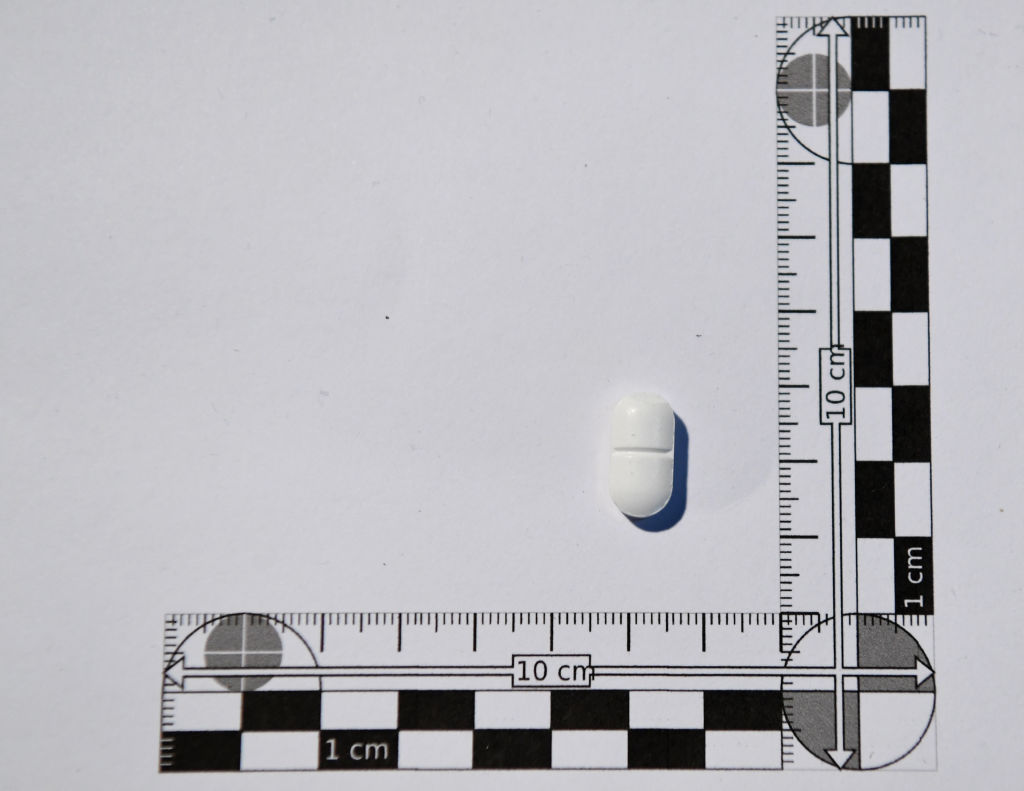

If we want to reverse the growing trend of overdose deaths, naloxone, a drug that blocks the effects of opioids, must be distributed to everyone who is interacting with those who are dying, including the police. As well, it is time that we follow Spanos’s recommendation and make pill and drug testing available. Both would be first steps towards meeting the duty of care that people working in harm prevention, including police officers, have towards society and its citizens.