Australia–Japan security cooperation is about to get much deeper

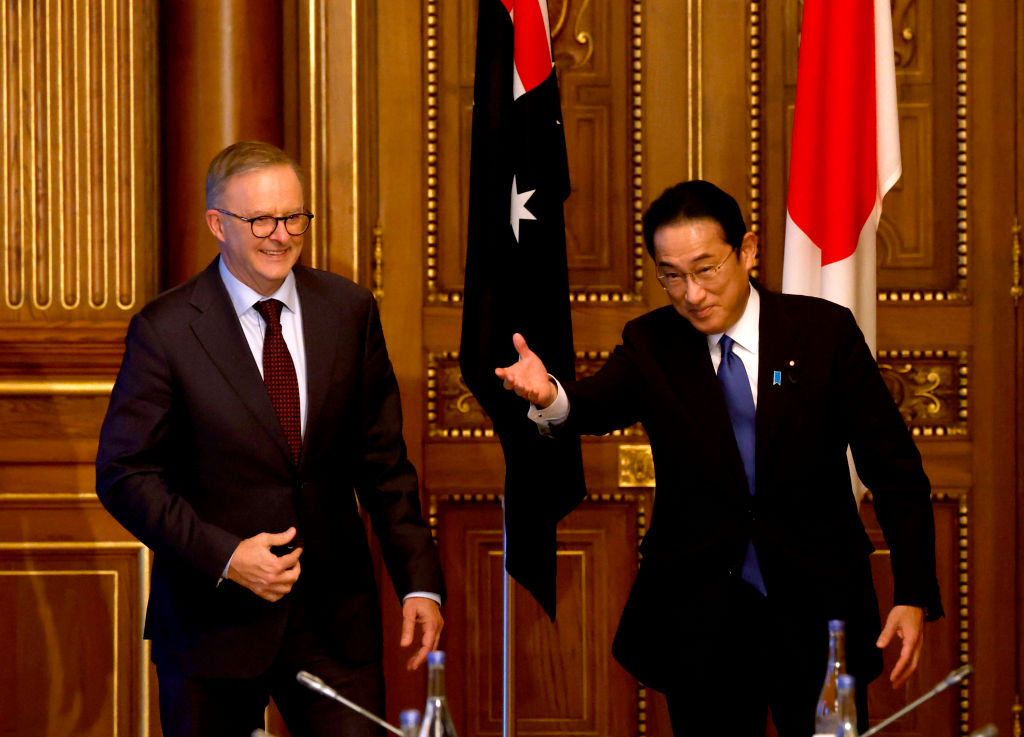

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is set to meet with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in Perth, Western Australia, this weekend. The meeting, their second face to face since Albanese took office in May, is keenly anticipated to be another groundbreaking event in Australia–Japan relations as the two countries further strengthen their ‘special strategic partnership’ in the face of an ever more challenging security environment in the Indo-Pacific. The choice of Perth as the venue is symbolic; as Japan’s ambassador to Australia, Shingo Yamagami, has commented, ‘Perth is the ideal setting—located at the geopolitical nexus of Australia and the Indo-Pacific, and the economic nexus of our own Japan–Australia relationship.’

Kishida and Albanese are expected to announce an updated version of the Australia–Japan Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation, which has effectively served as the foundational document of the strategic partnership when it was signed back in 2007. Much has changed in the intervening years, and both parties have long considered the need to revise the declaration to reflect shifts in the strategic environment and further consolidate and deepen their bilateral cooperation across a spectrum of activities.

What might we reasonably expect from the new joint declaration?

We can assume that it will codify the efforts at ‘deepening cooperation in the areas of security and defense and economy’ that have taken place within the strategic partnership over the past 15 years, such as the two countries’ agreements on information sharing, logistics and military interoperability (including, most recently, the reciprocal access agreement). The bilateral agreement for transfers of defence equipment and technology, put in place in 2014 to facilitate Japan’s (ultimately unsuccessful) bid to provide submarines to Australia, may gain a new lease of life as the two countries explore ways to jointly develop or produce military hardware. This dovetails with a stated desire to work together on ‘game-changing’ technologies such as quantum computing, artificial intelligence and hypersonics.

Indeed, with joint recognition of the vital importance of ‘economic security’ issues, not only in relation to defence, but also in areas such as energy security and supply-chain resilience, the two countries will likely signal ways in which they will ensure access to critical minerals and hydrogen production. Notably, Japan has instituted a cabinet-level economic security minister to oversee its economic security strategy—something Australia should also seriously consider. Cyber security, space security and an emphasis on countering environmental security issues brought about by climate change will be additional features on the joint agenda for cooperation.

The new declaration will also likely signal both countries’ commitment to multilateral institutions in the Indo-Pacific, with acknowledgement of ‘ASEAN centrality’, but also with a stated preference for the East Asia Summit as the most important venue for regional security dialogue (given the presence of the United States). They will affirm their support for economic institutions such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, and for engagement with the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity.

But the declaration will also emphasise the new array of ‘minilateral’ institutions—small-group targeted cooperation between select states, such as the Australia–Japan–US security dialogue and the Quad, and possibly noting Japan’s support of AUKUS. This reflects their stated commitment to ‘further coordination with allies and like-minded countries’.

Though it’s unlikely that China will be mentioned by name, Beijing’s actions, including military pressure across the Taiwan Strait and against Japan itself in the East China Sea, and the use of economic coercion as a tool of statecraft, are obvious inclusions. Any direct reference to the security of Taiwan will predictably produce a counterblast from Beijing, as witnessed in its responses to earlier statements by the partners.

Given Pyongyang’s recent missile launches over Japan, North Korea will certainly rate a significant mention, possibly couched in line with an earlier stated intention to achieve a ‘world without nuclear weapons’ and observance of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative.

Russia’s coercive actions also extend to the Indo-Pacific region, despite its war in Ukraine, as it continues military activities close to Japan (where Tokyo has a territorial dispute over the Northern Territories/Kurile Islands) and elsewhere in combination with its ‘no limits’ partner, China.

Given the mounting strategic tensions in the South Pacific as a result of China’s increasing penetration of the region—for example, through the 2022 Beijing–Honiara ‘security agreement’—the Pacific islands will likely feature prominently as an area for renewed cooperation. Australia and Japan crafted a joint strategy for cooperation in the South Pacific in 2016 to coordinate their approaches to development aid and capacity-building in the region. But the recent appearance of the Partnership for the Blue Pacific, involving Australia and Japan alongside the US, UK and New Zealand, will be a further minilateral venue for the two partners to expedite their regional agenda.

The new declaration will further establish the Australia–Japan strategic partnership as a major platform in both countries’ strategic responses to the deteriorating security environment in the Indo-Pacific. As has been repeatedly stated, it is based upon ‘shared interests and values’. Among the two nations’ shared interests is the desire to maintain peace and stability while advancing economic prosperity in an increasingly contested region. Shared values include their mutual championship of a rules-based order, based upon international law and peaceful resolution of disputes, backed by a shared commitment to freedom, democracy and human rights.

As strategic competition in the region intensifies, the strategic partnership mechanism is seen as an important vehicle to jointly safeguard mutual security objectives, both as a supplement to the US alliance system and as a limited insurance policy against a renewed period of American isolationism, as was partly experienced under the Trump administration. That is, it serves both a reinforcing and a hedging purpose with respect to US regional engagement.

Those expecting the new declaration to formalise a mutual military defence treaty will likely be disappointed. While the strategic partnership continues to deepen and expand in the direction of a typical alliance, and is sometimes referred to as a ‘quasi-alliance’ or ‘semi-alliance’ by commentators, these are more characterisations than official policy. Neither side will feel the need for, or be prepared to bear the consequences of, announcing a formal military alliance or treaty at this time. While the Australian government had proposed such a treaty at the outset of the partnership, which was declined by Tokyo, and some in both countries continue to advocate for a treaty, the strategic partnership has served, and will continue to serve, as an effective proxy for advancing their joint vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific.