Air arrivals are Australia’s most pressing border security challenge

By the end of last week parliamentarians and sections of the media (see here and here) had all offered opinions on whether independent MP Kerryn Phelps’ medical evacuation bill would restart the people-smuggling trade to Australia.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison went as far as to say that ‘the beast was stirring’. In my own analysis, I argued that the bill would spark hope of a future life in Australia in those ‘desperate souls lost across the region and the globe’.

Putting aside this binary and occasionally emotive discourse, it’s rather disturbing that for six years Australia’s public policy dialogue on asylum seekers and refugees has consistently coalesced around irregular maritime arrivals and offshore processing. These issues are important, but boat arrivals have slowed markedly, and those that are embarking on a journey to Australia are being turned around or towed back as part of Operation Sovereign Borders.

Unfortunately, the debate on offshore processing has drowned a much-needed broader discussion on the challenges facing our humanitarian migration program.

Australia’s humanitarian migration policies are delivered by two programs: onshore and offshore. The larger of the two is the offshore humanitarian program, which is divided into two categories. The first is the ‘refugee’ category, which is focused on ‘people who are subject to persecution in their home country and are in need of resettlement’.

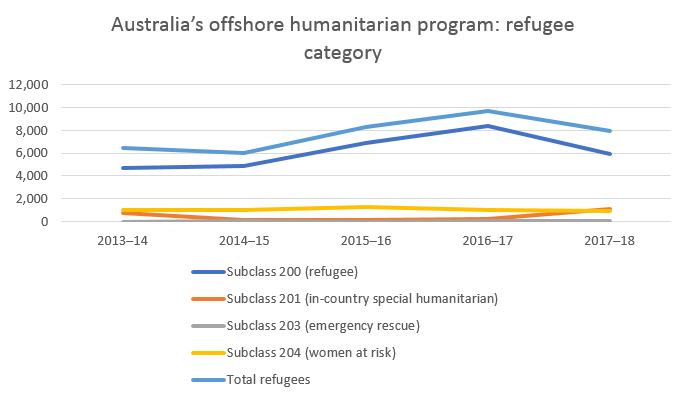

Applications for these places are submitted to Australia’s overseas missions. The following graph provides a visual analysis of the visas granted in this category over the last five years. It seems odd that we haven’t debated why the number of grants for visa subclass 204, ‘women at risk’, is at a five-year low (from 1,043 in 2013–14 to 940 in 2017–18).

The second category is the special humanitarian program. This program is for those who are ‘subject to substantial discrimination amounting to gross violation of human rights in their home country and have a link to Australia’. The graph below provides a visual analysis of the overall composition of the offshore humanitarian program. Over the last five years, an increasing percentage of Australia’s offshore humanitarian visas have been granted to those with existing connections to or links with Australia. There’s been little in the way of public discussion on why these changes have occurred, or whether the government is looking to civil society to do more to assist the resettlement of special humanitarian category refugees.

Australia’s onshore humanitarian program is composed of irregular maritime and air arrivals. While the boats have been stopped, the number of people travelling to Australia by air on student or tourist visas, for example, and claiming asylum on arrival has changed significantly over the last two years.

In 2016–17, 18,290 applications for protection visas were lodged; in 2017–18 this jumped to 27,931. In 2017–18 only 18% of these claims were granted. As the number of claims rises, the Australian Border Force (ABF) and Department of Home Affairs are expending increasing resources on processing applications lodged onshore, more than 80% of which are rejected.

Most of the applications in both 2016–17 (59%) and 2017–18 (66%) were lodged by Malaysian and Chinese citizens. Surprisingly, there’s been little public debate as to why the number of Chinese citizens applying for protection jumped from 2,269 in 2016–17 to 9,315 in 2017–18.

In 2016–17, Australia granted 1,711 protection visas and 1,435 the following financial year. When it comes to successful applications, there’s been remarkably little discussion about why only 2% of Malaysian citizen protection visa applications and 10% of Chinese citizen applications are granted.

In his foreword to ASPI’s 2017 report People smugglers globally, former immigration minister Phillip Ruddock argued that ‘a cohesive, resilient, multicultural Australia can be generous within our capacity to help those in greatest need. That is reliant upon strong border security.’ I would argue that the integrity of Australia’s border security is now being challenged by the increasing number of rejected onshore applications originating from air arrivals. This, and not the prospect of more boat arrivals, should be seen as Australia’s most pressing migration and border issue.

It’s easy to see why Home Affairs has used extraterritorial methods to assist Australia’s migration controls, including the implementation of strict visa requirements, the use of sanctions for carriers that bring incorrectly documented arrivals, the deployment of ABF airline liaison officers, the use of biometric technologies and the occasional excising of territory for the purposes of the Migration Act. These measures are critical to reducing the number of onshore applications—whether they be maritime or air arrivals. They are important to maintaining the integrity of Australia’s border, but also serve to reduce the workload involved in processing and managing the growing number of onshore protection visa rejections.

The fact remains that the demand for humanitarian resettlement already far exceeds the places made available through resettlement countries’ humanitarian programs. Globally, the number of people needing humanitarian resettlement is growing by the day, and climate change is likely to accelerate this trend. While debate on whether the maritime people smuggler beast is stirring rages for a second week, discussion on the broader trends in Australia’s on- and offshore humanitarian program remains muted.

While we need to resolve what to do with those asylum seekers on Manus Island and Nauru, we also need to work out how to address the growing number of onshore protection applications. A bigger strategic challenge is how to work more effectively with the international community on ways to mitigate the factors that are undermining human safety and security across the globe.