Protecting critical national infrastructure in an era of IT and OT convergence

ASPI Policy Brief 18/2019

What’s the problem?

Today, we’re seeing an increasing convergence between the digital and the physical worlds. This is sometimes referred to as the convergence of IT (information technology) and OT (operational technology)—devices that monitor physical effects, control them, or both. More and more devices are becoming interconnected to create the ‘internet of things’ (IoT).

While this brings many benefits, it also brings new types of risks to be managed—a cyberattack on OT systems can have consequences in the physical world and, in the context of a critical national infrastructure provider, those physical consequences can have a potentially major impact on society.

Insecure OT systems can also be a back door to allow attackers to penetrate IT systems that were otherwise thought to be well secured.

Among Australian critical national infrastructure providers, the level of maturity and understanding of the specific risks of OT systems lags behind that of IT systems. There’s a shortage of people with OT security skills, commercial solutions are less readily available, and boards lack specialist knowledge and experience. Mandating or recommending standards could help boards understand what’s expected of them, but it isn’t clear which standards are appropriate for managing these risks.

What’s the solution?

A lesson learned from IT security over the past decade is that impacts are severe unless security is considered up front and threats are managed proactively rather than reactively. As the convergence of IT and OT gathers pace in our critical national infrastructure, urgent action on a range of fronts is needed to address risks introduced by the IT–OT convergence.

Concerted effort is needed to ensure that boards of critical infrastructure organisations are mandated and enabled to decide, communicate and monitor their OT cyber risk appetite; that the right skills and tools are available to address the problems; and that there’s effective sharing of threat intelligence and best practice. Achieving this will require the prioritisation of resources to appropriate parts of government to support these actions.

This paper looks at critical infrastructure policy in Australia, the convergence of cyber and physical systems, and the risk and threat environment applicable to those systems. It then looks at the current state of maturity and how this could be improved, concluding with policy recommendations.

What are OT, ICS and SCADA?

OT refers to operational technology. Gartner defines it as ‘hardware and software that detects or causes a change through the direct monitoring and/or control of physical devices, processes and events’.1

Other terms commonly used in discussions of this area are ICSs (industrial control systems), which are a key sector in OT, and often a key area of concern since, as the name suggests, they’re used to control major industrial processes such as power plants. ICSs are often managed via SCADA (supervisory control and data acquisition) systems, so SCADA cybersecurity is a key focus, as the compromise of the SCADA system allows full control of the industrial process.

This report uses the term OT throughout, as this refers to the full range of cyber–physical systems that should be considered in developing policy approaches to securing critical infrastructure.

Convergence creates risk

IT and OT systems have traditionally been separate but have converged in recent years, as OT devices that monitor and control ‘real-world’ physical systems are increasingly connected to the internet or wider communication networks, in particular in our critical national infrastructure providers.

For example, managers may be provided with a dashboard of the performance of a power plant, allowing operational changes (such as changing load generation) and commercial decisions (such as the execution and pricing of electricity sale contracts) to be made in real time.

Although this brings clear benefits, it also brings new risks. OT systems are no longer isolated and stand-alone, so a cyberattack on the internet-connected combined IT–OT system can have direct physical consequences. When the organisation is part of our critical national infrastructure, such an attack can have a potentially major impact on national security.

Research and survey methodology

This study examined the understanding and management of the risks of IT–OT convergence in critical national infrastructure, particularly the telecommunications, energy, water and transport sectors. These areas are considered the most critical to the security of Australia and are the focus of government legislation. Many of the issues of IT–OT convergence identified here occur in other sectors of the economy and society, although exploring the implications outside of critical infrastructure is beyond the scope of this paper.

This paper drew on desktop research; interviews with key stakeholders in major Australian critical infrastructure providers, generally targeting the senior risk owners, government officials and subject-matter experts; and a survey of a limited sample of critical infrastructure operators (a dozen organisations in the four priority sectors). The survey explored approaches to IT–OT convergence, the level of understanding of the risks, and approaches to managing the risks.

Critical national infrastructure in Australia

In Australia, the federal, state and territory governments have defined critical infrastructure as:

those physical facilities, supply chains, information technologies and communication networks which, if destroyed, degraded or rendered unavailable for an extended period, would significantly impact the social or economic wellbeing of the nation or affect Australia’s ability to conduct national defence and ensure national security.2

Examples include the systems providing food, water, energy, transport, communications and health care.

Critical infrastructure providers in Australia cover a broad range of organisation types—some are government agencies or government-owned corporations, but a large proportion are run by commercial organisations, which may be privately owned companies, public corporations or part of multinational organisations. Government-owned providers may be at the federal, state or local government level, with differing access to resources and security expertise.

The policy for critical infrastructure resilience was launched by then Attorney-General George Brandis in 2015, and is now the responsibility of the Department of Home Affairs. Australian policy sets out two key objectives: to improve the management of reasonably foreseeable risks, and to improve resilience to unforeseen events. Much of our critical infrastructure is owned and operated by commercial organisations and the strategy recognises that, so implementation is intended to be through a broadly non-regulatory business–government partnership.

The Critical Infrastructure Centre was established in January 2017 with a mandate to work across all levels of government and with owners and operators to identify and manage the risks to Australia’s critical infrastructure. It aims to bring together expertise from across the Australian Government to manage complex and evolving national security risks to critical infrastructure from espionage, sabotage and foreign interference. Although other forums, such as the Trusted Information Sharing Network (TISN), look across a broader range of critical infrastructure sectors and threats, budget constraints mean that the Critical Infrastructure Centre has focused on a more limited range of sectors that pose the greatest potential threat to national security if attacked. Therefore, the initial work has focused on understanding potential foreign ownership and control risks, enabled by the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018, which mandates obligations for a range of assets that meet specified thresholds in the electricity, gas, water and ports sectors (currently estimated to number around 165).

In managing broader security risks from potential foreign or domestic actors attacking our critical infrastructure, the Critical Infrastructure Centre also administers the telecommunications sector security reforms, which are based on the Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2017, which came into force on 18 September 2018. The reforms place obligations on providers in the telecommunications sector to ensure the security of their networks and to notify government of changes with potential security impacts, and enable government to obtain information to monitor compliance and to direct providers to do ‘a specified thing that is reasonably necessary to protect networks and facilities from national security risks’.

Cyber–physical convergence

Critical national infrastructure providers are typically significant users of OT in order to automate the services that they provide. They’re under pressure to deliver services more efficiently and at lower cost, due to market competition, technological change, reduced government funding and price regulation.

To achieve this, organisations have sought to automate and integrate more and more of their IT and OT systems. Research for this report showed that, although most organisations hadn’t seen much change in their degree of IT–OT convergence over the past two years, in the next two years they expect a rapid increase in convergence. Most providers interviewed for this report expect a high degree of convergence and extensive two-way connectivity.

Another convergence driver is the proliferation of interconnected devices, often referred to as the ‘industrial internet of things’ (IIoT). This has been helped by the development of open standards, low-powered sensors and electronic controllers, and short-range communication networks.

In the past, an organisation might have had a ‘stovepiped’ system provided by a single vendor communicating using proprietary protocols, with a single gateway into the back-office IT system.

Today, it’s more likely that there will be a range of different vendor systems communicating with each other in a complex mesh network, and the concept of a clear boundary between IT and OT domains is less relevant. A Kaspersky study of 320 worldwide professional OT security decision-makers showed that 53% saw implementing these types of IIoT solutions as one of their top priorities.3

As the volume of data grows due to the exponential increase in connected sensors, the data can be mined to monitor operational performance, scheduling and utilisation, faults and anomalies, compliance and so on. It can, in turn, be used to identify actions to improve effectiveness, often in real time. However, to implement effective machine learning and artificial intelligence algorithms, it is often easiest to connect to today’s public cloud services, which can provide flexible and easy-to-use processing power. This results in a more porous border between corporate IT systems and public networks, and effectively interconnects OT networks with public networks. Although the use of cloud services can bring security opportunities, unless managed appropriately it can bring new vulnerabilities by making formerly separate corporate systems accessible through the wider internet.

Some commentators have noted that getting full value from this sort of data analysis requires close partnership between the users and manufacturers of OT systems. Gartner predicts that, by 2020, 50% of OT service providers will create key partnerships with IT-centric providers for IoT offerings.4 Another report suggests that 95% of organisations using the IoT have some form of partnership with another organisation to implement their IoT solutions, so it’s likely that even for the other 50% of providers many will still have features and services that expect the OT devices to be connected to the internet.5

Communications technologies are also improving: 5G network rollouts by Telstra and Optus are expected to enable better latency and availability for remote applications. This means we’re likely to see more interconnectedness between IT and OT systems not only within organisations but between organisations and supply chains, further increasing complexity and the potential cyberattack surface.

Challenges of OT cybersecurity

The key principles may be similar, but IT cybersecurity is considered much more mature and advanced than OT cybersecurity. This is because IT systems are much more prevalent, the risks are well recognised and there are enough case studies of real-life attacks to ensure focus and understanding of how to address the risks. Historically, OT systems were physically isolated, and cybersecurity was not a priority until the recent convergence trend drove it up the agenda.

There are significant overlaps and similarities, and OT cybersecurity can learn much from IT cybersecurity. Probably 80% of the threats are the same as for IT systems, but it’s with the other 20% where the biggest challenges lie. Some of the key differences are as follows:

- The risk calculus is different. A successful OT attack can cause major physical damage or even loss of life, which can make a significant difference to the risk appetite.

- For OT systems, the availability of service is often more important than confidentiality, whereas in IT that priority is often reversed. Shutting down a system to stop an attack might not be an option for an OT system, and even applying updates to fix known vulnerabilities may not always be feasible. Integrity is also more important, given the potential safety-critical impact of changes to data.

- The operational lifetime of OT systems is typically much longer than that of IT systems. Plant and machinery can last 20–50 years, whereas IT systems may be replaced every 3–5 years. Older systems might not be built to withstand modern threats, and support and security patches might not be available.

- The threat and attack models are different. Typically, the design of firewalls and security monitoring tools is based on characteristic indicators of IT attacks, meaning that OT attacks could pass through undetected.

The risk and threat environment

A cyberattack on an OT system is not just theoretical—there have already been many publicly reported attacks. As long ago as 2001, a disgruntled subcontractor used remote radio access to release sewage into town water, parks and other areas in Australia.6

More recent examples include suspected nation-state-motivated attacks on Saudi Arabian industry. In 2012, Saudi Aramco, the Saudi national oil company, was hit by a major attack that disabled 35,000 computers, halting all its operations, even though OT systems were not directly attacked.7 In August 2017, attackers breached the safety control systems at a Saudi petrochemical plant, intending to sabotage them and cause an explosion. Fortunately, it appears that a coding error meant they were unsuccessful.8

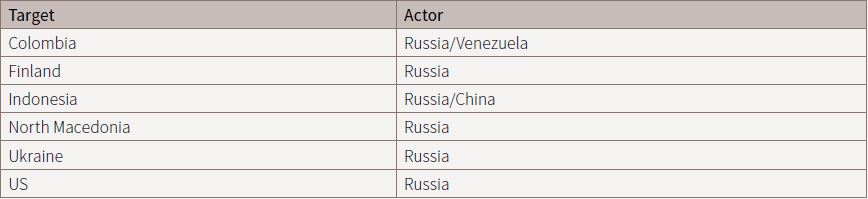

Other energy companies have also been targeted. In December 2015, a Ukrainian electricity distribution company’s control systems were breached in an attack subsequently attributed to Russia.9 The operator had to switch to manual mode, and approximately 225,000 customers lost power in what was the first publicly acknowledged cyber incident to result in power outages.10

In March 2018, the US Government issued an alert that Russian Government actors were remotely targeting US Government energy, nuclear, water and other critical infrastructure sectors, carrying out reconnaissance as a potential precursor to targeted attacks.11 Interestingly, it appeared to be a multi-stage campaign in which the attackers first targeted small commercial facilities’ networks and then used those systems as a bridge to move into the networks of larger, more critical organisations— an example of exploiting the type of supply-chain connectivity mentioned above.

So far, reported attacks have affected the availability of services, which can still have major impacts on society, but through good design, good fortune, or both, major direct physical impacts have been avoided. However, if the aim of an adversary is to cause significant physical damage and potentially loss of life, it is conceivable that they could compromise the integrity of the systems not only by sabotaging control systems but by modifying monitoring systems to override fail-safe mechanisms and alarms. Fortunately, we haven’t seen any such incidents to date, at least from publicly available information, but the Saudi petrochemical company attack showed this intent, making it a very real possibility that policymakers need to address.

Another class of threat is the potential use of unsecured OT systems as an entry point for penetration of a connected IT system that may otherwise be well protected. Examples of exploitation of unsecured consumer IoT devices have recently been seen; for example, the Mirai botnet ‘weaponised’ devices such as CCTV cameras with default credentials to launch a massive distributed denial-of-service attack.12

The current state of maturity: survey results

At a high level, there’s clear awareness of the threat from IT–OT convergence. The Kaspersky study mentioned above showed that 77% of companies ranked cybersecurity as a major priority, 66% saw targeted attacks as a major concern, and 77% believed that they were likely to be the target of an OT cybersecurity incident.13 Two-thirds saw the advent of the IIoT as bringing even more significant OT security risks.

In all discussions with Australian providers for this report, cyber risks were recognised from board level all the way down through the organisation. While only one organisation of the 12 interviewed had a clear directive on its OT risk appetite, most providers were cautious, stating that their OT risk tolerance was lower than for IT systems, and an assessment of benefits versus risks was made before interconnecting systems. OT cyber risk is reported at least quarterly to the board in two-thirds of the organisations, although it’s normally combined with IT risk rather than reported as a stand-alone item.

It was encouraging that in seven out of 12 cases there was at least one director at board level with some expertise in the area. Over 80% of respondents said they had participated at least occasionally in the sharing of lessons learned and best practice for both IT and OT security across their sector, which perhaps reflects the active engagement of the TISN and other organisations.

However, many organisations clearly felt there was scope to do better. Half said there was room for improvement in their understanding of the degree of convergence in their systems and in ensuring that they had a comprehensive view of the risks and vulnerabilities. Less than half were able to confirm that vulnerability testing of their OT systems was carried out at least annually. Although 11 out of 12 had an approved incident response plan that had been tested within the past 12 months, in a third of cases the OT security incident response plan was considered to be the same as the IT security incident response plan. The different approaches for isolating and recovering from OT attacks, and the focus on availability in OT, mean that recycling the IT response plan for this sort of incident is unlikely to be effective. This probably explains why two-thirds of organisations felt they were only partially prepared or underprepared to respond to a real incident.

An approach for managing the risks—and some of the challenges in doing so

Research for this report suggests several approaches to improve security as a result of IT–OT convergence.

Setting expectations

Effective security starts with leadership. Boards need to provide strong awareness and sponsorship, setting and communicating their risk appetite in a way that drives their approach to IT–OT convergence. Given the lack of board members with specific expertise, the key will be to encourage and enable boards to be more inquisitive—creating a culture in which they can ask questions and explore issues in an open and transparent manner. This shift in board understanding and engagement is what has occurred in recent years with ‘traditional’ cybersecurity.

Critical infrastructure providers have to deal with conflicting pressures, such as maintaining service quality, reducing costs, regulating prices and more. It’s important that government recognises the threats and mandates that providers face to ensure the security of their systems. For government organisations, the recent NSW cyber strategy is a good example that sets a clear mandate for all government agencies to ensure that there are ‘no gaps in cyber security’ related to physical systems.14

A different approach may be needed for commercial providers—not all of them recognise the commercial risk of a security incident and act accordingly, and hence some compulsion and enforcement are probably required. For regulated industries, licence conditions are often used to place clear obligations on providers, although as this is typically done at the state or local level there may be variability across the nation. The telecommunications sector security reform regulations place more specific obligations on telecommunications providers, such as reporting planned changes and potential direction powers; the operation and applicability of this framework should be reviewed to see whether a modified approach would be appropriate for other sectors.

Of course, just mandating or setting a vision is not sufficient; action is needed to see it realised. The right tools need to be made available to enable providers to embed a culture of security throughout the organisation, and the right governance to ensure that this is happening.

Risk identification and management

No single control will eliminate the risk of a cyberattack; hence, given the potentially catastrophic impacts if an incident occurs, providers need to be very clear about their risk appetite as they potentially converge IT and OT. They must build a clear understanding of the various systems—physical systems, networks, software, computers and other devices—and their interdependencies and connectivity. This should allow analysis of potential threat vectors and allow a risk register to be developed and maintained.

Idaho National Lab has proposed a step-by-step approach for mission-critical systems, called ‘consequence-driven, cyber-informed engineering’, to identify the functions whose failure could have catastrophic consequences.15 It proposes that for the ‘crown jewels’ the approach should be to minimise any internet connectivity, and put in analogue monitoring and fail-safes to protect against the risk of failure or sabotage of digital systems. This has already been implemented as a year-long pilot at Florida Power & Light, one of the largest electric utilities in the US. The case for such an approach might not be proven in all cases, but discussion using this sort of framework may help to drive a better definition of risk appetite.

Where the decision is made to converge systems, a ‘defence-in-depth’ approach should be used to reduce the risks. This could include appropriate network segregation, physical security measures, gateways, system and device configurations, user access controls and so on. These need to be backed up by regular monitoring of systems and networks to identify anomalous patterns of behaviour and to investigate them in real time. The costs of defence in depth will clearly need to be factored into decision-making about the efficiency and benefits of specific IT–OT convergence plans.

Given the differences between IT and OT security, the right tools need to be chosen: an IT firewall might not protect an OT network from malicious traffic, and a standard IT security monitoring solution might not detect OT attacks, as the characteristics of hostile activity will be different. Critical infrastructure providers have commented on the lack of mature commercially available solutions to assist with this, although other industry experts consulted suggested the problem may in some areas be overlapping, competing solutions along with unrealistic marketing claims. An appropriate framework would help to assess these claims and identify any gaps in the market where government intervention may be appropriate, whether this is investment to help accelerate development or certifications for products to help buyers assess their efficacy for solving their problems.

Standards and guidance

Standards are always an emotive subject, especially when it comes to security. The right standards can work well in setting a baseline, provided they’re implemented as part of an overall strategy and not as a blind tick-the-box exercise. However, inappropriate standards will at best give a misleading picture and at worst may drive insecure behaviours.

The limited survey conducted for this report asked about some common standards and found that, while the information security standard ISO27001 and the risk management standard ISO31000 were used by 58% and 33% of respondents, respectively, the business continuity standard ISO22301 and the US Department of Energy’s Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (ES-C2M2) cyber maturity framework hardly seem to be used at all. However, over 80% were either actively using or considering other OT-specific security standards.

While the research for this report was underway, the Australian Energy Market Operator published the inaugural report into the cyber maturity of energy operators. This was based on self-assessments against a framework developed specifically for this purpose but drawing on a number of international standards as well as Australian Signals Directorate guidance and Australian legislation. The companies voluntarily completed 67 self-assessments, the details of which have not been released, but the conclusion of the report was that the responses ‘identified opportunities to improve cyber security maturity across the sector’.16

Standards should be reviewed on a sector-by-sector basis—for example, using a guiding council of experts in a given sector—in order to identify which standards should be recommended as suitable for organisations to adopt and regularly audit against.

Education

The general shortage of cybersecurity skills in the workforce has been well documented and discussed,17 but a recurring theme from interviews for this report was an even more acute challenge involving the availability of suitably skilled OT security professionals.

Education will be the key to addressing this gap. This should start with broad user education, as part of building the right culture across an organisation, supplemented by the right policies and processes. This can help avoid some of the most common weaknesses. For example, it’s thought that some of the attacks described above were facilitated by a well-meaning employee inserting an unknown USB stick into a computer to check who it belonged to, and a study by Honeywell18 found that 44% of USB devices present at surveyed industrial facilities had a security issue. Common resources should be created for use in general user education and executive awareness.

The Academic Centres of Cyber Security Excellence program19 should include specific provision for OT security courses to be created, either as stand-alone courses or as part of broader curriculums.

Courses should be available both for those entering the workforce and as ongoing education and professional development for those in the industry. Formal education can be supplemented by other approaches, such as a program of secondments between IT and OT security teams. In any case, while an OT security team needs to be specialised and focused on this area, it will need to work closely with IT security professionals to share expertise and also to identify and stop threats that cross the domains.

Sharing threat information

In cybersecurity, we’re stronger together, and OT security is no exception. Given the relative lack of maturity and the potential risks, it’s vital that there are effective mechanisms for sharing threat information and lessons learned. There seems to be a divide in the availability of sector-specific OT threat intelligence—two-thirds of organisations surveyed for this report received it regularly, but one-third said they received it rarely or not at all. The sharing of OT security information seems to be noticeably less common than for IT security; the reasons cited included resources, contact details and security clearances being focused on IT security.

Several organisations within government can help with building cross-sector threat intelligence information and disseminating it, including the TISN, the Australian Cyber Security Centre and the Business and Government Liaison Unit in the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation. However, there need to be clear leadership and ownership to make this happen, not just by top-down information flow from government but by facilitating sharing between peers in each sector.

This should also be accessible to a broad range of geographically dispersed stakeholders—tier 1 major companies can attend summits in Canberra, but local councils running transport or water companies won’t have the resources for extensive travel. It’s possible that the Critical Infrastructure Centre’s TISN could take on this leadership role, but it would require a significant boost in resources and a change in its operating model to be able to do so.

Incident response readiness

Organisations need to ensure that they have clear response and recovery plans for attacks. The plans need to go beyond theoretical documents that are dusted off and read only when something goes wrong. As noted, there’s room for improvement in testing incident response plans, but organisations need to go one step further with active war-gaming exercises that bring together boards, executives and business continuity teams to work through scenarios, and technical red-team testing that simulates the potential activity of an attacker to test detection and response capabilities.

The Australian Cyber Security Centre runs a national program for the owners and operators of Australia’s critical infrastructure that uses exercises and other readiness activities that target strategic decision-making, operational and technical capabilities, strategic engagement and communications. Additional resources could be provided to ensure that this is extended to cover OT security incident scenarios and is accessible across the spectrum of critical infrastructure providers.

Conclusions and recommendations

Given the potential impact to society and our national security from the accelerating convergence of IT and OT systems, it’s important that this issue is prioritised and managed effectively. Research for this report has shown a general lack of focus, mature understanding and effective solutions. Some of the measures outlined above are already being implemented, but may still need accelerating or boosting, and some are more critical than others. The top three recommendations are as follows:

- Boards of critical infrastructure providers need to explicitly set their OT cyber risk tolerance and monitor their organisation’s performance against it. This requires a combination of regulatory mandate and enforcement (building on existing regulatory models, learning from the experience in implementing the telecommunications sector security regulations, and enabling boards to manage risk); for example, through recommended standards and approaches tailored to each sector. Considering ‘worst-case’ outcomes may lead to a list of critical assets that by default should not be connected to external systems unless there are a compelling benefit and robust measures to manage the security risks arising from the connection. The Critical Infrastructure Centre would appear to be best placed to coordinate and drive this across Australia to ensure a common best-practice approach.

- Better education and information are needed at all levels to improve the understanding and management of risks, from both a business and a technical point of view. Key areas for action are:

- General awareness and training. Specialised skills will be in short supply, but boards can be enabled to be curious to ask the right questions to understand and measure the risks and build the right culture, and all users should be educated in threat awareness and basic ‘hygiene’ to remove some of the easy targets for attackers.

- Specialist courses. The creation and delivery of specific OT security courses should be included in plans for university, TAFE and other institutional programs.

- Better threat information sharing. Clarity should be provided on the current range of government agencies that can help with threat intelligence sharing, providing clear leadership and ownership of this responsibility for the critical infrastructure sector.

- Technical information sharing. There appears to be a perception that there’s a lack of appropriate commercial solutions for protecting OT systems, but globally the market can appear crowded. The maturity of commercial solutions specifically to address OT security requirements should be reviewed. This information could be shared with providers and also used to identify whether there’s a gap that may merit government investment to help accelerate the development of the capabilities needed.

The Australian Cyber Security Centre could lead this activity, aligned with its existing programs of work.

- Resources need to be prioritised to ensure that the appropriate organisations are able to implement all of the required actions at the required pace. The longer that action is delayed, the more of a head start malicious actors will have, the more convergence will have taken place without security being at the core, and the greater will be the threat.

Address by author Rajiv Shah at launch event.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Aakriti Bachhawat for her assistance in running the survey, and all those who took the time to respond. Thanks also to those respondents and other government and industry experts who made themselves available for discussions that provided valuable input to this paper.

What is ASPI?

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non‑partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally.

ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre

The ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre’s mission is to shape debate, policy and understanding on cyber issues, informed by original research and close consultation with government, business and civil society. It seeks to improve debate, policy and understanding on cyber issues by:

- conducting applied, original empirical research

- linking government, business and civil society

- leading debates and influencing policy in Australia and the Asia–Pacific.

The work of ICPC would be impossible without the financial support of our partners and sponsors across government, industry and civil society. This research was made possible thanks to the generous support of Thales.

Important disclaimer

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in relation to the subject matter covered. It is provided with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering any form of professional or other advice or services. No person should rely on the contents of this publication without first obtaining advice from a qualified professional.

© The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Limited 2019

This publication is subject to copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. Notwithstanding the above, educational institutions (including schools, independent colleges, universities and TAFEs) are granted permission to make copies of copyrighted works strictly for educational purposes without explicit permission from ASPI and free of charge.

- Gartner, Inc., ‘Operational technology (OT)’, IT glossary, no date, online. ↩︎

- Australian Government, Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy, 2010, online. ↩︎

- Wolfgang Schwab, Mathieu Poujal, The state of industrial cybersecurity 2018, CXP Group, June 2018, online. ↩︎

- Christy Petty, ‘When IT and operational technology converge’, Smarter with Gartner, 13 January 2017, online. ↩︎

- Gemalto, The state of IoT security, 2018, online. ↩︎

- Michael Crawford, ‘Utility attack led to security overhaul’, Computerworld Australia, 16 February 2006, online. ↩︎

- Jose Pagliery, ‘The inside story of the biggest hack in history’, CNN Money, 5 August 2015, online. ↩︎

- Nicole Perlroth, Clifford Krauss, ‘A cyberattack in Saudi Arabia had a deadly goal. Experts fear another try’, New York Times, 15 March 2018, online. ↩︎

- John Hultquist, ‘Threat research: Sandworm team and the Ukrainian power company attacks’, FireEye, 7 January 2016, online. ↩︎

- Electricity Information Sharing and Analysis Center, Analysis of the cyber attack on the Ukrainian power grid: defense use case, 18 March 2016, online. ↩︎

- US Department of Homeland Security, ‘Alert (TA18‑074A): Russian Government cyber activity targeting energy and other critical infrastructure sectors’, US Government, 16 March 2018, online. ↩︎

- Josh Fruhlinger, ‘The Mirai botnet explained: how teen scammers and CCTV cameras almost brought down the internet’, CSO, 9 March 2018, online. ↩︎

- Schwab & Poujal, The state of industrial cybersecurity 2018. ↩︎

- Digital NSW, NSW Government policy: cyber security policy, NSW Government, February 2019, online. ↩︎

- Office of Scientific and Technical Information, Consequence-driven cyber-informed engineering (CCE), US Department of Energy, 18 October 2018, online. ↩︎

- Australian Energy Market Operator, 2018 summary report into the cyber security preparedness of the national and WA wholesale electricity markets, December 2018, online. ↩︎

- AustCyber, Australia’s cyber security sector competitiveness plan, Australian Cyber Security Growth Network, 2018, online. ↩︎

- Honeywell, Honeywell industrial USB threat report: universal serial bus (USB) threat vector trends and implications for industrial operators, 2019, online. ↩︎

- Department of Education and Training, ACCSE program guidelines, Australian Government, 13 February 2017, online. ↩︎

Little has changed in the defence funding picture since last year. This year’s budget continues to follow the trajectory of solid real annual increases set out in the 2016 Defence White Paper. The consolidated defence budget (that is, the budget for the Department of Defence and the Australian Signals Directorate) reaches $38.7 billion in 2019–20. Real growth is only 1.3%—the smallest increase under the Coalition government—and the budget has actually decreased slightly as a percentage of GDP (from 1.94% to 1.93%) because GDP has grown faster than the defence budget.

Little has changed in the defence funding picture since last year. This year’s budget continues to follow the trajectory of solid real annual increases set out in the 2016 Defence White Paper. The consolidated defence budget (that is, the budget for the Department of Defence and the Australian Signals Directorate) reaches $38.7 billion in 2019–20. Real growth is only 1.3%—the smallest increase under the Coalition government—and the budget has actually decreased slightly as a percentage of GDP (from 1.94% to 1.93%) because GDP has grown faster than the defence budget.