This report accompanies the Mapping China’s Tech Giants website.

This is our first report on the topic – updated reports are also available;

Executive summary

Chinese technology companies are becoming increasingly important and dynamic actors on the world stage. They’re making important contributions in a range of areas, from cutting-edge research to connectivity for developing countries, but their growing influence also brings a range of strategic considerations. The close relationship between these companies and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) raises concerns about whether they may be being used to further the CCP’s strategic and geopolitical interests.

The CCP has made no secret about its intentions to export its vision for the global internet. Officials from the Cyber Administration of China have written about the need to develop controls so that ‘the party’s ideas always become the strongest voice in cyberspace.’1 This includes enhancing the ‘global influence of internet companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu [and] Huawei’ and striving ‘to push China’s proposition of internet governance toward becoming an international consensus’.

Given the explicitly stated goals of the CCP, and given that China’s internet and technology companies have been reported to have the highest proportion of internal CCP party committees within the business sector,2 it’s clear these companies are not purely commercial actors.

ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre has created a public database to map the global expansion of 12 key Chinese technology companies. The aim is to promote a more informed debate about the growth of China’s tech giants and to highlight areas where this expansion is leading to political and geostrategic dilemmas. It’s a tool for journalists, researchers, policymakers and others to use to understand the enormous scale and complexity of China’s tech companies’ global reach.

The dataset is inevitably incomplete, and we invite interested users to help make it more comprehensive by submitting new data through the online platform.

Our research maps and tracks:

- 17,000+ data points that have helped to geo-locate 1700+ points of overseas presence for these 12 companies;

- 404 University and research partnerships including 195+ Huawei Seeds for the Future university partnerships;

- 75 ‘Smart City’ or ‘Public Security Solution’ projects, most of which are in Europe, South America and Africa;

- 52 5G initiatives, across 34 countries;

- 119 R&D labs, the greatest concentration of which are in Europe;

- 56 undersea cables, 31 leased cable and 17 terrestrial cables;

- 202 data centres and 305 telecommunications & ICT projects spread across the world.

Introduction

China’s technology, internet and telecommunications companies are among the world’s largest and most innovative. They’re highly competitive, and many are leaders in research and development.

They’ve played a central role in bringing the benefits of modern technology to hundreds of millions of people, particularly in the developing world.

As a function of their increasingly global scale and scope, China’s tech giants can exert increasing levels of influence over industries and governments around the world. The close relationship between Chinese companies and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) means that the expansion of China’s tech giants is about more than commerce.

A key research question includes: What are the geostrategic, political and human rights implications of this expansion? By mapping the global expansion of 12 of China’s largest and most influential technology companies, across a range of sectors, this project contributes new data and analysis to help answer such questions.

All Chinese companies are subject to China’s increasingly stringent security, intelligence, counter-espionage and cybersecurity laws.3 That includes, for example, requirements in the CCP constitution4 for any enterprise with three or more full party members to host internal party committees, a clause in the Company Law5 that requires companies to provide for party activity to take place, and a requirement in the National Intelligence Law to cooperate in and conceal involvement in intelligence work.6

Several of the companies included in this research are also directly complicit in human rights abuses in China, including the reported detention of up to 1.5 million Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang.7 From communications monitoring to facial recognition that enables precise and pervasive surveillance, advanced technology – from these and other companies – is crucial to the increasingly inescapable surveillance net that the CCP has created for some Chinese citizens.

Every year since 2015, China has ranked last in the annual Freedom on the Net Index.8 The CCP has made no secret of its desire to export its concepts of internet and information ‘sovereignty’,9 as well as cyber censorship,10 around the world.11 Consistent with that directive, this research shows that Chinese companies are playing a role in aiding surveillance and providing sophisticated public security technologies and expertise to authoritarian regimes and developing countries that face challenges to their political stability, governance and rule of law.

In conducting this research, ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre (ICPC) has used open-source information in English and Chinese to track the international operations and investments of12 major Chinese technology companies: Huawei, ZTE, Tencent, Baidu, China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC), Alibaba, China Mobile, China Telecom, China Unicom, Wuxi, Hikvision and BGI.

This research has been compiled in an online database that ICPC is making freely accessible to the public. While it contains more than 1,700 projects and more than 17,000 data points, it’s not exhaustive. We welcome and encourage members of the public to help us make this dataset more complete by submitting data via the website.

The database

Throughout 2018, ICPC received frequent questions from media and stakeholders about the international activities of Chinese technology companies; for example, about Huawei’s operations in particular regions or how widespread the use of Baidu or WeChat is outside of China.

These were always difficult questions to answer, as there’s a lack of publicly available quantitative and qualitative data, and some of these companies disclose little in the way of policies that affect data, security, privacy, freedom of expression and censorship. What information is available is spread across a wide range of sources and hasn’t been compiled. In-depth analysis of the available sources also requires Chinese-language capabilities, an understanding of Chinese state financing structures, and the use of internet archiving services as web pages are moved, altered or even deleted.

A further impediment to transparency is that Chinese media are under increasing control from the CCP and publish few investigative reports, which severely limits the available pool of media sources. The global expansion and influence of US internet companies, particularly Facebook, for example, has rightly received substantial attention and scrutiny over the past few years. Much of that scrutiny has come from, and will continue to come from, independent media, academia and civil society.

However, the same scrutiny is often lacking when it comes to Chinese tech and social media companies. The sheer capacity of China’s giant tech companies, their reach and influence, and the unique party-state environment that shapes, limits and drives their global behaviour set them apart from other large technology companies expanding around the world.

This project seeks to:

- Analyse the global expansion of a key sample of China’s tech giants by mapping their major points of overseas presence.

- Provide the public with an analysis of the governance structures and party-state politics from which those companies have emerged and with which they’re deeply entwined.

The data and map is available here: https://chinatechmap.aspi.org.au/

Methodology

To fill this research gap, ICPC sought to create an interactive global database to provide policymakers, academics, journalists, government officials and other interested readers with a more holistic picture of the increasingly global reach of China’s tech giants.

A complete mapping of all Chinese technology companies globally would be impossible within the confines of our research. ICPC has therefore selected 12 companies from across China’s telecommunications, technology, internet and biotech sectors:

- Alibaba

- Baidu

- BGI

- China Electronics Technology Group (CETC)

- China Mobile

- China Telecom

- China Unicom

- Hikvision (a subsidiary of CETC)

- Huawei

- Tencent

- Wuxi

- ZTE

This dataset will continue to be updated during 2019. This research relied on open-source information in English and Chinese. This has included company websites, corporate information, tenders, media reporting, databases and other public sources.

The size and complexity of these companies, and the speed at which they’re expanding, means this dataset will inevitably be incomplete. For that reason, we encourage researchers, journalists, experts and members of the public to contribute and submit data via the online platform in order to help make the dataset more complete over time.

China’s tech firms & the CCP

The CCP’s influence and reach into private companies has increased sharply over the past decade.

In 2006, 178,000 party committees had been established in private firms.12 By 2016, that number had increased sevenfold to approximately 1.3 million.13 Today, whether the companies, their leadership, and their employees like it or not, the CCP is present in private and public enterprise. Often the activity of party committees and party-building activity is linked to the CCP’s version of the concept of ‘corporate social responsibility’14—a concept that the party has explicitly politicised. For instance, in the publishing industry, corporate social responsibility includes political responsibility15 and protecting state security.16 Internet and technology companies are believed to have the highest proportion of CCP party committees in the private sector.17

This expanding influence and reach also extends to foreign companies. For example, by the end of 2016, the CCP’s Organisation Department claimed that 70% of China’s 100,000 foreign enterprises possessed party organisations.18 Expanding the party’s reach and role inside private enterprises appears to have been a priority since party chief Jiang Zemin’s ‘Three Represents’ policy, which opened party membership to businesspeople, became CCP doctrine in 2002.

All the companies mapped as a part of this project have party committees, party branches and party secretaries. For example, Alibaba has around 200 party branches;19 in 2017 it was reported that Tencent had 89 party branches;20 and Huawei has more than 300.21

Sometimes, the relevance and significance of the CCP’s presence within technology companies is dismissed or trivialised as merely equivalent to the presence of government relations or human resources departments in Western corporations. However, the CCP’s expectations of these committees is clear.22 The CCP’s constitution states that a party organisation ‘shall be formed in any enterprise … and any other primary-level work unit where there are three or more full party members’.23 Article 32 outlines their responsibilities, which include encouraging everyone in the company to ‘consciously resist unacceptable practices and resolutely fight against all violations of party discipline or state law’. Article 33 states that party committees inside state-owned enterprises are expected to ‘play a leadership role, set the right direction, keep in mind the big picture, ensure the implementation of party policies and principles, and discuss and decide on major issues of their enterprise in accordance with regulations’.24

The establishment and expansion of party committees in private enterprises appears to be one of the ways in which Beijing is trying to reduce financial risks and exercise control over the economy. Because entities ‘cannot be without the party’s voice’ and ‘must safeguard the state-owned assets and interests from damage’,25 the party committees are expected to weigh in on major decisions and policies, including the appointment and dismissal of important cadres, major project investment decisions and large-scale capital expenditures.26

Although this guidance is longstanding practice in state-owned enterprises, it also appears to be taking root in private enterprises. Conducting a review of corporate disclosures in 2017, the Nikkei Asian Review identified 288 companies listed in China that ‘changed their articles of association to ensure management policy that reflects the party’s will’.27 In 2018, 26 publicly listed Chinese banks revised their articles of association to support party committees and the establishment of subordinate discipline inspection committees. Many of the revised articles reportedly include language requiring party consultation before major decisions are made.28

This control mechanism is explicit in the party’s vetting of business leaders. For example, although he’s not a party member, Baidu CEO Robin Li is a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the country’s primary ‘united front’ body.29 The party conducts a comprehensive assessment of any of the business executives brought into official advisory bodies managed by the United Front Work Department, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference and the National People’s Congress. Two of the four criteria – which relates to a business person’s political inclinations – include, their ‘ideological status and political performance’, as well as their fulfillment of social responsibilities. And second, their personal compliance with laws and regulations.30

Enabling & exporting digital authoritarianism

The crown jewel of Chinese foreign policy under Xi Jinping is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which is to be a vast global network of infrastructure intended to enable the flow of trade, people and ideas between China and the rest of the world.31 Technology, under the banner of the Digital Silk Road, is a key component of this project.

China’s ambitions to influence the international development of technological norms and standards are openly acknowledged.32 The CCP recognises the threat posed by an open internet to its grip on power—and, conversely, the opportunities that dominance over global cyberspace could offer by extending that control.33

In a 2017 article published in one of the most important CCP journals, officials from the Cyber Administration of China (the top Chinese internet regulator) wrote about the need to develop controls so that ‘the party’s ideas always become the strongest voice in cyberspace.’34 This includes enhancing the ‘global influence of internet companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu [and] Huawei’ and striving ‘to push China’s proposition of internet governance toward becoming an international consensus’.

Officials from the Cyberspace Administration of China have written that ‘cyberspace has become a new field of competition for global governance, and we must comprehensively strengthen international exchanges and cooperation in cyberspace, to push China’s proposition of Internet governance toward becoming an international consensus.’35 China’s technology companies are specifically referenced as a part of this effort: ‘The global influence of Internet companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, Huawei and others is on the rise.’36

Western technology firms have attracted heated criticism for making compromises in order to engage in the Chinese market, which often involves constraining free speech or potentially abetting human rights abuses.37 This attention is warranted and should continue. However, strangely, global consumers have so far been less critical of the Chinese firms that have developed and deployed sophisticated technologies that now underpin the CCP’s ability to control and suppress segments of China’s population38 and which can be exported to enable similar control of other populations.

The ‘China model’ of digitally enabled authoritarianism is spreading well beyond China’s borders. Increasingly, the use of technology for repression, censorship, internet shutdowns and the targeting of bloggers, journalists and human rights activists are becoming standard practices for non-democratic regimes around the world.

In its 2018 Freedom on the net report, Freedom House singled out China as the worst abuser of human rights on the internet. The report also found that the Chinese Government is actively seeking to export its moral and ethical norms, expertise and repressive capabilities to other nations. In addition to the Chinese Government’s efforts, Freedom House specifically called out the role of the Chinese tech sector in facilitating the spread of digital repression. It found that Chinese companies:

have supplied telecommunications hardware, advanced facial-recognition technology, and data analytics tools to a variety of governments with poor human rights records, which could benefit Chinese intelligence services as well as repressive local authorities. Digital authoritarianism is being promoted as a way for governments to control their citizens through technology, inverting the concept of the internet as an engine of human liberation.39

Reporters Without Borders has also sounded the alarm over the involvement of Chinese technology companies in repressing free speech and undermining journalism. As part of an extensive report on the Chinese Government’s attempts to reshape the world’s media in its own image, it concluded that:

From consumer software apps to surveillance systems for governments, the products that China’s hi-tech companies try to export provide the regime with significant censorship and surveillance tools … In May 2018, the companies were enlisted into the China Federation of Internet Societies (CFIS), which is openly designed to promote the Chinese Communist Party’s presence within them. Chinese hi-tech has provided the regime with an exceptional influence and control tool, which it is now trying to extend beyond China’s borders.40

Pushing back against both the practices of digital authoritarianism and the norms and values that underpin such practices requires a clear-eyed understanding of the way they’re being spread. For example, a study of the BRI has found that the ways in which some BRI projects, including digital projects, are structured create serious concerns about the erosion of sovereignty for host nations, such as when a recipient government doesn’t have full control of the operations, management, digital infrastructure or data being generated through those projects.41

Sovereign governments are, of course, ultimately responsible for their actions. For some, particularly Western governments, this includes being transparent and accountable in their use of technology for surveillance and information control. And, if they aren’t, the media, civil society and the public have avenues to hold them to account. However, companies also have responsibilities in this space, which is why many sensitive and dual-use technologies are subject to export controls. The need for companies to be held accountable for how new technologies are used is particularly acute in developing countries, where the state may be less able or less willing to do so because of challenges arising from governance, legislative and regulatory capacity, transparency and corruption.

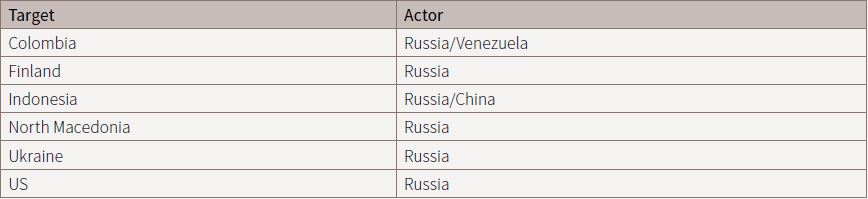

The following case studies have been selected as illustrations of the ways in which Chinese technology companies, often with funding from the Chinese Government, are aiding authoritarian regimes, undermining human rights and exerting political influence in regions around the world.

Surveillance cities: Huawei’s ‘smart cities’ projects

An important and understudied part of the global expansion of Chinese tech companies involves the proliferation of sophisticated surveillance technologies and ‘public security solutions’.42 Huawei is particularly dominant in this space, including in developing countries where advanced surveillance technologies are being introduced for the first time.

Through this research and as of April 2019, we have mapped 75 Smart City-Public Security projects, most of which involve Huawei.43 Those projects—which are often euphemistically referred to as ‘safe city’ projects—include the provision of surveillance cameras, command and control centres, facial and licence plate recognition technologies, data labs, intelligence fusion capabilities and portable rapid deployment systems for use in emergencies.

The growth of Huawei’s ‘public security solution’ projects has been rapid. For example, the company’s ‘Hisilicon’ chips reportedly make up 60% of chips used in the global security industry.44 In 2017, Huawei listed 40 countries where its smart-city technologies had been introduced;45 in 2018, that reach had reportedly more than doubled to 90 countries (including 230 cities). Because of a lack of detail or possible differences in definition, this project currently covers 43 countries.46

This research has found that, in many developing countries, exponential growth is being driven by loans provided by China Exim Bank (which is wholly owned by the Chinese Government).47 The loans, which must be paid back by recipients,48 are provided to foreign governments, and it’s been reported in academia and the media that the contractors used must be Chinese companies.49 In many of the examples examined, Huawei was awarded the primary contract; in some cases, the contract was managed by a Chinese state-owned enterprise and Huawei played a ‘sub-awardee’ role as a provider of surveillance equipment and services.50

Smart-city technologies can impart substantial benefits to states using them. For example, in Singapore, increased access to digital services and the use of technology that exploits the ‘internet of things’ (for traffic control, health care and video surveillance) has led to increased citizen mobility and productivity gains.51

However, in many cases, Huawei’s safe-city solutions focus on the introduction of new public security capabilities, including in countries such as Ecuador, Pakistan, the Philippines, Venezuela, Bolivia and Serbia. Many of those countries rank poorly, some very poorly, on measures of governance and stability, including the World Bank’s governance indicators of political stability, the absence of violence, the control of corruption and the rule of law.52

Of course, the introduction of new public security technologies may have made cities ‘safer’ from a crime prevention perspective, but, unsurprisingly, in some countries it’s created a range of political and capacity problems, including alleged corruption; missing money and opaque deals;53 operational and ongoing maintenance problems;54 and alleged national security concerns.55

Censorship and suppression: aiding authoritarianism in Zimbabwe

The example set by the Chinese state is increasingly being looked to by non-democratic regimes—and even some democratic governments—as proof that a free and open internet is neither necessary nor desirable for development. ‘If China could become a world power without a free Internet, why do African countries need a free internet?’ one unnamed African leader reportedly asked interviewers from the Department of Media Studies at the University of Witwatersrand.56

The business dealings of Chinese technology companies in Zimbabwe, for example, are closely entwined with the CCP’s support for the country’s authoritarian regime. China is Zimbabwe’s largest source of foreign investment, partly as a result of sanctions imposed by Western countries over human rights violations by the regime. Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s first visit outside of Africa after his election was to China, where he thanked President Xi Jinping and China for supporting Zimbabwe against Western sanctions and called for even deeper economic and technical cooperation between the two nations.57

Chinese companies play a central role in Zimbabwe’s telecommunications sector. Huawei has won numerous multimillion-dollar contracts with state-owned cellular network NetOne, some of which have been the subject of corruption allegations.58 Several of Huawei’s Zimbabwe projects have been financed through Chinese Government loans.59

ZTE also has a significant footprint in the country (and has also been the subject of corruption allegations).60 This has included a $500 million loan, in partnership with China Development Bank, to Zimbabwe’s largest telco, Econet, in 2015.61 ZTE has previously provided equipment, including radio base stations, for Econet’s 3G network.62 Zimbabwean telecommunications providers currently owe millions of dollars to Huawei and ZTE, as well as Ericsson, which reportedly led to network disruptions in March 2019.63

The CCP and Chinese companies haven’t just helped to cushion Zimbabwe’s leaders against the impact of sanctions. They’re also providing both a model and means for the regime’s authoritarian practices to be brought forward into the digital age, both online and offline.

The Zimbabwean Government has been considering draconian new laws to restrict social media since at least 2016, when the official regulator issued an ominous warning to internet users against ‘generating, passing on or sharing such abusive and subversive materials’.64 In the same year, a law was passed to allow authorities to seize devices in order to prevent people using social media.65

In early 2019, the government blocked social media and imposed internet shutdowns in response to protests against fuel price increases. Information Minister Energy Mutodi stated that ‘social media was used by criminals to organize themselves … this is why the government had to … block [the] internet,’ as he announced plans for forthcoming cybercrime laws to criminalise the use of social media to spread ‘falsehoods’.66

The government has openly been looking to China as a model for controlling social media,67 including by creating a cybersecurity ministry, which a spokesperson described as ‘like a trap used to catch rats’.68

Parts of this ‘trap’ reportedly come from China. In 2018, it was reported that China, alongside Russia and Iran, had been helping Zimbabwe to set up a facility to house a ‘sophisticated surveillance system’ sold to the government by ‘one of the largest telecommunications companies’ in China.69 Given the description and context, it seems plausible that this company may be Huawei or ZTE.

‘We have our means of seeing things these days, we just see things through our system. So no one can hide from us, in this country,’ said former Intelligence Minister Didymus Mutasa.70

The government is increasingly looking to expand its surveillance from the online space into the real world. It’s signed multiple agreements with Chinese companies for physical surveillance systems, including a highly controversial planned national facial recognition system with Chinese company CloudWalk.71

It’s also interested in developing its own indigenous facial recognition technology, and is working with CETC subsidiary Hikvision to do it.72 Hikvision is already supplying surveillance cameras for police and traffic control systems.73 In 2018, Zimbabwean authorities signed a memorandum of understanding with the company to implement a ‘smart city’ program in Mutare. This included the donation of facial recognition terminals equipped with deep-learning artificial intelligence (AI) systems.

In a media statement, the government stated:

The software is meant to be integrated with the facial recognition hardware which will be made locally by local developers in line with the government’s drive to grow the local ICT sector making Zimbabwe to be the number one country in Africa to spearhead the facial recognition surveillance and AI system nationwide in Zimbabwe.74

National ID programs: Venezuela’s ‘Fatherland Card’

Chinese tech companies are involved in national identity programs around the world. One of the most concerning examples is playing out amid the political and humanitarian crisis in Venezuela. A Reuters investigation in 2018 uncovered the central role played by ZTE in inspiring and implementing the Maduro regime’s ‘Fatherland Card’ program.75 The Fatherland Card (Carnet de la Patria) records the holder’s personal data, such as their birthday, family information, employment, income, property owned, medical history, state benefits received, presence on social media, membership of a political party and history of voting.

Although the card is technically voluntary, without it Venezuelans can be denied access to government-subsidised food, medication or gasoline.76 In the midst of Venezuela’s political crisis, registering for a ‘voluntary’ card is no choice at all for many. In fact, people in Caracas are queuing for hours to get hold of one, despite the risks of handing over personal data to the increasingly unstable and repressive Maduro regime.77

According to Reuters, ZTE was contracted by the government to build the underlying database and accompanying mobile payment system. A team of ZTE employees was embedded with Cantv, the Venezuelan state telecommunications company that manages the database, to help secure and monitor the system. ZTE has also helped to build a centralised government video surveillance system.

There are concerns that the card program is being used as a tool to interfere in the democratic process. During the 2018 elections, observers reported kiosks being set up near or even inside voting centres, where voters were encouraged to scan their cards to register for a ‘fatherland prize’.78 Those who did so later received text messages thanking them for voting for Maduro (although they never did get the promised prize).

Authorities claim that the cards record whether a person voted, but not whom they voted for. However, an organiser interviewed by Reuters claimed to have been instructed by government managers to tell voters that their votes could be tracked. Regardless of the truth of the matter, even the rumours that the government may be watching who votes for it—or, perhaps more pertinently, against it—could be expected to influence the way people vote.

In the context of the current crisis, this technologically enabled population control takes on an even sharper edge. Cyberspace has emerged as a key battleground in the struggle between the Maduro regime and the Venezuelan opposition led by Juan Guaidó.

In addition to selective social media blocks79 and total internet shutdowns,80 there’s also evidence of more insidious attacks. For example, a website set up by the opposition to coordinate humanitarian aid delivery was subject to a DNS hijacking attack, including the theft of the personal data of potentially thousands of pro-opposition volunteers.81

Cantv, Venezuela’s government-run telecommunications company, is reportedly ‘dependent on agreements with ZTE and Huawei to supply equipment and staff and … Cantv sends its employees to China to receive training.’82 These deals are financed through the Venezuela China Joint Fund. China is known as something of an international leader in DNS blocking and manipulation, and the Chinese Government is strongly supporting the Maduro regime, including by targeting social media users in China who post or share content critical of Maduro.83

Shaping politics and policy in Belarus

In some parts of the world, Chinese technology companies are helping shape the politics and policy of new technologies through the development of high-level relationships with national governments. This is particularly concerning in the case of non-democratic countries.

Often referred to as ‘Europe’s last dictatorship’, Belarus has been under the control of authoritarian strongman Aleksandr Lukashenko since 1994.84 In recent years, ties with China have come to play an increasingly significant role not only in Belarus’s delicate diplomatic relations with its powerful neighbours, but also in its very indelicate domestic policies of violent repression. This has included the use of digital technologies for mass surveillance and the targeted persecution of activists, journalists and political opponents.85

Huawei has been supplying video surveillance and analysis systems to the Lukashenko regime since 2011 and border monitoring equipment since at least 2014.86 Also in 2014, Huawei’s local subsidiary, Bel Huawei Technologies, launched two research labs for ‘intellectual remote surveillance systems’. Through the labs, Huawei provides ‘laboratory-based training … for the specialists of Promsvyaz, Beltelekom, HSCC and other organisations’.87

Over the past several years, collaboration between the Belarusian Government and Chinese technology companies has expanded rapidly, in line with Belarus’s engagement with the BRI and with deepening diplomatic and economic ties between Lukashenko’s regime and the CCP.88

In March 2019, Belarus unveiled a draft information security law. ‘It is purely our own product. We didn’t borrow it from anyone,’ State Secretary of the Security Council Stanislav Zas told Belarusian state media.89

A day later, China’s ambassador to Belarus spoke to the same outlet about how ‘Belarusian and Chinese companies [have] managed to establish intensive cooperation in the area of cyber and information security’, and about the desire of both countries to ‘expand cooperation in the sphere of cybersecurity’.90

‘Both countries have good practice in this field. We are going to even deeper cooperate [sic] and share experience,’ the Chinese ambassador said.

Huawei has played an especially prominent role in this process at multiple levels. It has continued and expanded the training it provides to Belarusians, including sending students to study in China and signing an agreement with the Belarusian State Academy of Communications for a joint training centre.91

Huawei is also exerting political and policy influence. In May 2018, the company released its National ICT priorities for the Republic of Belarus.92 The proposal includes recommendations for ‘public safety’ technologies, such as video surveillance and drones, and a citizen status identification system.

‘Belarus has not yet widely deployed integrated police systems, and thus can refer to the solution adopted in Shenzhen,’ the document notes. This is likely to be a reference to the facial recognition program implemented by Shenzhen police to ‘crack down on jaywalking’.93

During a meeting with the chairman of Huawei’s board, Guo Ping, for the launch of the plan, then Belarusian Prime Minister Andrei Kobyakov expressed his hope that: the accumulated experience and prospects of cooperation will play an important role in the development of information and communication technologies in Belarus and in making friendship between our countries stronger. The Belarusian government counts on further effective interaction and professional cooperation.94

Controlling information flows—WeChat and the future of social messaging

Launched in 2011, WeChat quickly became China’s dominant social network but has largely struggled to build up a significant user base overseas. Still, of the social media super-app’s 1.08 billion monthly active users,95 an estimated 100–200 million are outside China.96

Southeast Asia provides the most fertile ground for WeChat outside of China: the app has 20 million users in Malaysia; 17% of the population of Thailand use it;97 and it’s the second most popular messaging app in Bhutan and Mongolia.98

The potential for WeChat to substantially grow its user base overseas remains, particularly as it hits a wall in user growth in China99 and overseas expansion becomes more of an imperative. To the extent that it’s being used outside of mainland China, WeChat poses significant risks as a channel for the dissemination of propaganda and as a tool of influence among the Chinese diaspora.

WeChat is increasingly used by politicians in liberal democracies to communicate with their ethnic Chinese voters, which necessarily means that communication is subject to CCP censorship by default.100

In one instance, in September 2017 Canadian parliamentarian Jenny Kwan posted a WeChat message of support for Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement – a series of pro-democracy protests that took place in 2014 – only to have it censored by WeChat.101

In 2018, Canadian police received complaints about alleged vote buying taking place on WeChat.102 A group called the Canada Wenzhou Friendship Society was reportedly using the app to offer voters a $20 ‘transportation fee’ if they went to the polls and encouraging them to vote for specific candidates.

Because WeChat is one of the main conduits for Chinese-language news, censorship controls help Beijing to ensure that news sources using the app for distribution report only news that serves the CCP’s strategic objectives.103

WeChat is not only a significant influence and censorship tool for the CCP, but also has the potential to facilitate surveillance. An Amnesty International study ranking global instant messaging apps on how well they use encryption to protect online privacy gave WeChat a score of 0 out of 100.104 Content that passes through WeChat’s servers in China is accessible to the Chinese authorities by law.105

Enabling human rights abuses in China: Uyghurs in Xinjiang

Many of the repressive techniques and technologies that Chinese companies are implementing abroad have for a long time been used on Chinese citizens. In particular, the regions of Tibet and Xinjiang are often at the bleeding edge of China’s technological innovation.

The complicity of China’s tech giants in perpetrating or enabling human rights abuses—including the detention of an estimated 1.5 million Chinese citizens106 and foreign citizens107—foreshadows the values, expertise and capabilities that these companies are taking with them out into global markets.

From the phones in people’s pockets to the tracking of 2.5 million people using facial recognition technology108 to the ‘re-education’ detention centres,109 Chinese technology companies—including several of the companies in our dataset—are deeply implicated in the ongoing surveillance, repression and persecution of Uyghurs and other Muslim ethnic minority communities in Xinjiang.

Many of the companies covered in this report collaborate with foreign universities on the same kinds of technologies they’re using to support surveillance and human rights abuses in China. For example, CETC—which has research partnerships with the University of Technology Sydney,110 the University of Manchester111 and the Graz Technical University in Austria112—and its subsidiary Hikvision are deeply implicated in the crackdown on Uyghurs in Xinjiang. CETC has been providing police in Xinjiang with a centralised policing system that draws in data from a vast array of sources, such as facial recognition cameras and databases of personal information. The data is used to support a ‘predictive policing’ program, which according to Human Rights Watch is being used as a pretext to arbitrarily detain innocent people.113 CETC has also reportedly implemented a facial recognition project that alerts authorities when villagers from Muslim-dominated regions move outside of prescribed areas, effectively confining them to their homes and workplaces.114

Huawei provides the Xinjiang Public Security Bureau with technical support and training.115 At the same time, it has funded more than 1,200 university research projects and built close ties to many of the world’s top research institutions.116 The company’s work with Xinjiang’s public security apparatus also includes providing a modular data centre for the Public Security Bureau of Aksu Prefecture in Xinjiang and a public security cloud solution in Karamay. In early 2018, the company launched an ‘intelligent security’ innovation lab in collaboration with the Public Security Bureau in Urumqi.117

According to reporting, Huawei is providing Xinjiang’s police with technical expertise, support and digital services to ensure ‘Xinjiang’s social stability and long-term security’.

Hikvision took on hundreds of millions of dollars worth of security-related contracts in Xinjiang in 2017 alone, including a ‘social prevention and control system’ and a program implementing facial-recognition surveillance on mosques.118 Under the contract, the company is providing 35,000 cameras to monitor streets, schools and 967 mosques, including video conferencing systems that are being used to ‘ensure that imams stick to a “unified” government script’.119

Most concerningly of all, Hikvision is also providing equipment and services directly to re-education camps. It has won contracts with at least two counties (Moyu120 and Pishan121) to provide panoramic cameras and surveillance systems within camps.

Future strategic implications

The degree to which nations and communities around the world are coming to rely on Chinese technology companies for critical services and infrastructure, from laying cables to governing their cities, has significant strategic implications both now and for many years into the future:

- Undermining democracy: Perhaps the greatest long-term strategic concern is the role of Chinese technology companies – and technology companies from other countries that aid or engage in similar behaviour – in enabling authoritarianism in the digital age, from supplying surveillance technologies to automating mass censorship and the targeting of political dissidents, journalists, human rights advocates and marginalised minorities. The most challenging issue is the continued export around the world of the model of vicious, ubiquitous surveillance and repression being refined now in Xinjiang.

- Espionage and intellectual property theft: The espionage risks associated with Chinese companies are clearly laid out in Chinese law, and the Chinese state has a well-established track record of stealing intellectual property.122 This risk is only likely to increase as ‘smart’ technology becomes ever more pervasive in private and public spaces. From city-wide surveillance to the phones in the pockets of political leaders (or, in a few years, the microphones in their TVs and refrigerators), governments, the private sector and civil society alike need to seriously consider how to better protect their information from malicious cyber actors.

- Developing technologies: Chinese companies are leading the field in research and development into a range of innovative, and strategically sensitive, emerging technologies. Their global expansion provides them with key resources, such as huge and diverse datasets and access to the world’s best research institutions and universities.123 Fair competition between leading international companies to develop these crucial technologies is only to be expected, and Chinese tech companies have made enormous positive contributions to the sum total of human knowledge and innovation. However, the strategic, political and ideological goals of the CCP—which has directed and funded much of this research—can’t be ignored. From AI to quantum computing to biotechnology, the nations that dominate those technologies will exercise significant influence over how the technologies develop, such as by shaping the ethical norms and values that are built into AI systems, or how the field of human genetic modification progresses. Dominance in these fields will give nations a major strategic edge in everything from economic competition to military conflict.

- Military competition: In cases of military competition with China, the Chinese Government would of course seek to leverage, to its own advantage, its influence over Chinese companies providing equipment and services to its enemies. This should be a serious strategic consideration for nations when they choose whether to allow Chinese companies to be involved in the build-out of critical infrastructure such as 5G networks, especially given the CCP’s increasing assertiveness and coercion globally.

This issue is particularly acute for countries already experiencing tensions over China’s territorial claims in regions such as the South China Sea. For example, in 2016, after a ruling by a UN-backed tribunal dismissed Chinese claims, suspected Chinese hackers attacked announcement and communications systems in two of Vietnam’s major airports, including a ‘display of profanity and offensive messages in English against Vietnam and the Philippines’.124 A simultaneous hack on a Vietnamese airline led to the loss of more than 400,000 passengers’ data. Vietnam’s Information and Communications Minister said that the government was ‘reviewing Chinese technology and devices’ in the wake of the attack.125 Cybersecurity firm FireEye says that it’s observed persistent targeting of both government and corporate targets in Vietnam that’s suspected to be linked to the South China Sea dispute.126

5G infrastructure build outs should be an area of particular concern. An article in the China National Defence Report in March 2019127 discusses the military applications for China of 5G in the move to ‘intelligentised’ warfare. ‘[A]s military activities accelerate towards extending into the domain of intelligentization, air combat platforms, precision-guided munitions, etc. will be transformed from ‘accurate’ to ‘intelligentized.’ 5G-based AI technology will definitely have important implications for these domains,’ write the authors, who appear to be researchers affiliated with Xidian University and the PLA’s Army Command Academy.

Conclusion

Chinese companies have unquestionably made important and valuable contributions to the technology industry globally, from contributing to cutting edge research and pushing the boundaries of developing technologies, to enabling access to affordable, good quality devices and services for people around the world. They are not going anywhere, and they are going to continue to play a vital role in the ways in which governments, companies and citizens around the world connect with one another.

At the same time, however, it is important to recognise that the activities of these companies are not purely commercial, and in some circumstances risk mitigation is needed. The CCP’s own policies and official statements make it clear that it perceives the expansion of Chinese technology companies as a crucial component of its wider project of ideological and geopolitical expansion. The CCP committees embedded within the tech companies and the close ties (whether through direct ownership, legal obligations or financing agreements including loans and lucrative contracts) between the companies and the Chinese government make it difficult for them to be politically neutral actors, as much as some of the companies might prefer this. There is also a legitimate question about whether global consumers should demand greater scrutiny of Chinese technology firms that facilitate human rights abuses in China and elsewhere.

Governments around the world are struggling with the political and security implications of working with Chinese corporations, particularly in areas such as critical infrastructure, for example in 5G, and in collaborative research partnerships that might involve sensitive or dual-use technologies. Part of this struggle is due to a lack of in-depth understanding of the unique party-state environment that shapes, limits and drives the global behaviour of Chinese companies. This research project aims to help plug that gap so that policymakers, industry and civil society can make more informed decisions when engaging China’s tech giants.

What is ASPI?

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non‑partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally.

ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre

The ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre’s mission is to shape debate, policy and understanding on cyber issues, informed by original research and close consultation with government, business and civil society.

It seeks to improve debate, policy and understanding on cyber issues by:

- conducting applied, original empirical research

- linking government, business and civil society

- leading debates and influencing policy in Australia and the Asia–Pacific.

The work of ICPC would be impossible without the financial support of our partners and sponsors across government, industry and civil society. ASPI is grateful to the US State Department for providing funding for this research project.

Important disclaimer

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in relation to the subject matter covered. It is provided with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering any form of professional or other advice or services. No person should rely on the contents of this publication without first obtaining advice from a qualified professional person.

© The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Limited 2019

This publication is subject to copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. Notwithstanding the above, educational institutions (including schools, independent colleges, universities and TAFEs) are granted permission to make copies of copyrighted works strictly for educational purposes without explicit permission from ASPI and free of charge.

Little has changed in the defence funding picture since last year. This year’s budget continues to follow the trajectory of solid real annual increases set out in the 2016 Defence White Paper. The consolidated defence budget (that is, the budget for the Department of Defence and the Australian Signals Directorate) reaches $38.7 billion in 2019–20. Real growth is only 1.3%—the smallest increase under the Coalition government—and the budget has actually decreased slightly as a percentage of GDP (from 1.94% to 1.93%) because GDP has grown faster than the defence budget.

Little has changed in the defence funding picture since last year. This year’s budget continues to follow the trajectory of solid real annual increases set out in the 2016 Defence White Paper. The consolidated defence budget (that is, the budget for the Department of Defence and the Australian Signals Directorate) reaches $38.7 billion in 2019–20. Real growth is only 1.3%—the smallest increase under the Coalition government—and the budget has actually decreased slightly as a percentage of GDP (from 1.94% to 1.93%) because GDP has grown faster than the defence budget.