Mapping more of China’s tech giants: AI and surveillance

This second report accompanies the Mapping China’s Technology Giants website.

Several report are now available on this topic;

- Mapping China’s Technology Giants (April 2019)

- Mapping More of China’s Technology Giants (this report – Nov 2019)

- Mapping China’s Technology Giants: Covid-19, supply chains and strategic competition (Jun 2021)

- Mapping China’s Technology Giants: Reining in China’s technology giants (Jun 2021)

Executive summary

ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre has updated the public database that maps the global expansion of key Chinese technology companies. This update adds a further 11 companies and organisations: iFlytek, Megvii, ByteDance (which owns TikTok), SenseTime, YITU, CloudWalk, DJI, Meiya Pico, Dahua, Uniview and BeiDou.

Our public database now maps 23 companies and organisations and is visualised through our interactive website, Mapping China’s Technology Giants. The website seeks to give policymakers, academics, journalists, government officials and other interested readers a more holistic picture of the increasingly global reach of China’s tech giants. The response to phase 1 of this project—it quickly became one of ASPI’s most read products—suggests that the current lack of transparency about some of these companies’ operations and governance arrangements has created a gap this database is helping to fill.

This update adds companies working mainly in the artificial intelligence (AI) and surveillance tech sectors. SenseTime, for example, is one of the world’s most valuable AI start-ups. iFlytek is a partially state-owned speech recognition company. Meiya Pico is a digital forensics and security company that created media headlines in 2019 because of its monitoring mobile app MFSocket.1 In addition, we’ve added DJI, which specialises in drone technologies, and BeiDou, which isn’t a company but the Chinese Government’s satellite navigation system.

We also added ByteDance—an internet technology company perhaps best known internationally for its video app, TikTok, which is popular with teenagers around the world. TikTok is also attracting public and media scrutiny in the US over national security implications, the use of US citizens’ data and allegations of censorship, including shadow banning (the down-ranking of particular topics via the app’s algorithm so users don’t see certain topics in their feed).

Company overviews now include a summary of their activities in Xinjiang.2 For some companies, including ByteDance and Huawei, we are including evidence of their work in Xinjiang that has not being reported publicly before. For most of these companies, the surveillance technologies and techniques being rolled out abroad—often funded by loans from the Export–Import Bank of China (China Eximbank)3—have long been used on Chinese citizens, and especially on the Uyghur and other minority populations in Xinjiang, where an estimated 1.5 million people are being arbitrarily held in detention centres.4 Some of these companies have actively and repeatedly obscured their work in Xinjiang, including in hearings with foreign parliamentary committees. This project now includes evidence and analysis of those activities in order to foster greater transparency about their engagement in human rights abuses or ethically questionable activities in the same way Western firms are held to account by Western media and civil society actors, as they should be.

In this report, we include a number of case studies in which we delve deeper into parts of the dataset. This includes case studies on TikTok as a vector for censorship and surveillance, BeiDou’s satellite and space race and CloudWalk’s various AI, biometric data and facial recognition partnerships with the Zimbabwean Government. We also include a case study on Meiya Pico’s work with China’s Public Security Ministry on Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aid projects in Southeast Asia and Central Asia.

Those projects include the construction of digital forensics labs and cyber capacity training, including for police forces across Asia.

We have also investigated the role that foreign investment plays in the global expansion of some of these companies, particularly in China’s surveillance and public security sector.

The updated database

Our public database now maps out 23 companies and organisations. On the Mapping China’s Technology Giants website you’ll find a dataset that geo-codes and analyses major points of overseas presence, including 5G relationships; ‘smart cities’ and ‘public security’ solutions; surveillance relationships; research and university partnerships; submarine cables; terrestrial cables; significant telecommunications and ICT projects; and foreign investment. The website does not map out products and services, such as equipment sales.

Previously, in April 2019, we mapped companies working across the internet, telecommunications and biotech sectors, including Huawei, Tencent, Alibaba, Baidu, Hikvision, China Electronics Technology Group (CETC), ZTE, China Mobile, China Telecom, China Unicom, Wuxi AppTec Group and BGI. This dataset has also been updated, and new data points have been added for those companies, including on 5G relationships, smart cities, R&D labs and data centres.

At the time of release this updated research project now maps and tracks:

- 26,000+ data points that have helped to geo-locate 2,500+ points of overseas presence for the 23 companies

- 447 university and research partnerships, including 195+ Huawei Seeds for the Future university partnerships

- 115 smart city or public security solution projects, most of which are in Europe, South America and Africa

- 88 5G relationships in 45 countries

- 295 surveillance relationships in 96 countries

- 145 R&D labs, the greatest concentration of which is in Europe

- 63 undersea cables, 20 leased cables and 49 terrestrial cables

- 208 data centres and 342 telecommunications and ICT projects spread across the world.

Other updates have also been made to the website, often in response to valuable feedback from policymakers, researchers and journalists. Updates have been made to the following:

Terrestrial cables have now been added and can be searched through the filter bar (via ‘Overseas presence’)

The original report that accompanied the launch of the project was translated into Mandarin in August 2019.

In addition to this dataset, each company has its own web page, which includes an overview of the company and a summary of its activities with the Chinese party-state. The overviews now include a summary of each company’s activities in Xinjiang. This research was added for a number of reasons.

First, we needed to compile the information in one place for journalists, civil society groups and governments. Second, these companies aren’t held to account by China’s media and civil society groups, and it’s clear that many have obscured their activities in Xinjiang. Some have even provided incorrect information in response to direct questions from foreign governments. For example, a Huawei executive told the UK House of Commons Science and Technology Committee on 10 June 2019 that Huawei’s activities in Xinjiang occurred only via ‘third parties:’8

Chair Sir Norman Lamb: But do you have products and services in Xinjiang Province in terms of some sort of contractual relationship with the provincial government?

Huawei Executive: Our contracts are with the third parties. It is not something we do directly.

That’s not correct. Huawei works directly with the Chinese Government’s Public Security Bureau in Xinjiang on a range of projects. Evidence for this—and similar—work can now be found via each company’s dedicated Mapping China’s Technology Giants web page and is also analysed below.

Methodology

ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre began this research project due to a lack of publicly available quantitative and qualitative data, especially in English, on the overseas activities of these key technology companies. Some of the companies disclose little in the way of policies that affect data, security, privacy, freedom of expression and censorship. What information is available is spread across a wide range of sources and hasn’t been compiled in one location. In-depth analysis of the available sources also requires Chinese-language capabilities and an understanding of other issues, such as the relationships the companies have with the state and how Chinese state financing structures work.

For example, some of the companies, especially Huawei, conduct a lot of their work in developing countries through China Eximbank loans. Importantly, the use of internet and other archiving services is vital, as Chinese web pages are often moved, altered or deleted.

This research relied on open-source data collection that took place primarily in English and Chinese. Data sources included company websites, corporate information, tenders, media reporting, databases and other public sources.

The following companies—which work across the telecommunications, technology, internet, surveillance, AI and biotech sectors—are now present on the Mapping China’s Technology Giants website (new additions are bold):

- Alibaba

- Baidu

- BeiDou

- BGI

- ByteDance

- China Electronics Technology Group (CETC)

- China Mobile

- China Telecom

- China Unicom

- CloudWalk

- Dahua

- DJI

- Hikvision (a subsidiary of CETC)

- Huawei

- iFlytek

- Megvii

- Meiya Pico

- SenseTime

- Tencent

- Uniview

- WuXi AppTec Group

- YITU

- ZTE.

The size and complexity of these companies, and the speed at which they’re expanding, mean that this dataset will inevitably be incomplete. For that reason, we encourage researchers, journalists, experts and members of the public to continue to contribute and submit data via the online platform in order to help make the dataset more complete over time.

For tips on how to get the most out of the map, navigate to ‘How to use this tool’ on the website. When you’re first presented with the map, all data points are displayed. Click the coloured icons and cables for more information. To navigate to the list of companies, click ‘View companies’ in the left blue panel.

There’s a filter bar at the bottom of the screen. Click the items to select. To reset your search selection, click ‘Reset’ in the filter bar.

The yellow triangle icons on the map are data points of particular interest in which we invested additional research resources.

These companies differ in their size, scope and global presence

They may not be household names in the West, but the market size of many of the Chinese companies outlined in this report is larger than many of their more well-known counterparts outside China. iFlytek, a voice recognition tech company established in 1999, isn’t yet a household name outside China but has 70% of the Chinese voice recognition market and a market capitalisation of Ұ63 billion (US$9.2 billion). Newcomer ByteDance, an internet technology company with a focus on machine-learning-enabled content platforms, was established only in 2012 but is already valued at around US$78 billion, making it the world’s most valuable start-up.

Many of the companies outlined in this report have skyrocketed in value by capitalising on China’s surge in security spending in Xinjiang and elsewhere as a large, sprawling surveillance apparatus is constructed. Some have been, in effect, conscripted into spearheading the development of AI in the country—a goal of particular strategic importance to the party-state.

Other companies we examine in this report, such as Dahua Technology, Megvii and Uniview, aren’t well known but have significant global footprints. Dahua, for example, is one of the world’s largest security camera manufacturers. Between them Hikvision9 and Dahua supply around one-third of the global market for security cameras and related goods, such as digital video recorders.10

All Chinese tech companies have deep ties to the Chinese state security apparatus, but, perhaps more than the others, the companies in this report occupy a space in which the lines between the commercial imperatives of private companies (and some state-backed companies) and the strategic imperatives of the party-state are blurred.

Several of the companies we examine—including iFlytek, SenseTime, Megvii and Yitu—have been designated as official ‘AI Champions’ by the party-state, alongside Huawei, Hikvision and the ‘BATs’ (Baidu,11 Alibaba12 and Tencent;13) which were featured in our previous report. These ‘champions’, having been identified as possessing “core technologies”, have been selected to spearhead AI development in the country, with the aim of overtaking the US in AI by 2030.14

Gregory C Allen, writing for the Center for a New American Security, cited SenseTime executives as saying the title:

… gave the companies privileged positions for national technical standards-setting and also was intended to give the companies confidence that they would not be threatened with competition from state-owned enterprises.15

Speaking in December 2018, SenseTime co-founder Xu Bing alluded to the uniqueness of this privileged position:

We are very lucky to be a private company working at a technology that will be critical for the next two decades. Historically, governments would dominate nuclear, rocket, and comparable technologies and not trust private companies.16

Historically, the party-state drew on the power of a few state-owned enterprises to help it achieve its strategic goals. But in order to become a world leader in AI by 2025—an express aim of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)— the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has demonstrated its ability to move away from those cumbersome organisations in favour of smaller, more agile companies not wholly owned by the state. This has proven to be a highly successful—and mutually beneficial—model.

Chinese AI and surveillance companies benefit from a highly favourable regulatory environment in which concerns over the potential use of invasive systems of surveillance to erode civil liberties are largely and substantively ignored by design, although they’re sometimes discussed in the Chinese media.17

Companies that we examine in this report, such as YITU, CloudWalk, iFlytek and SenseTime, have access to enormous customer databases that are generating huge amounts of proprietary data—the essential ingredient for improving AI and machine-learning algorithms.

AI giant SenseTime has access to a database of more than 2 billion images, at least some of which, SenseTime CEO Xu Li told Quartz,18 come from various government agencies, giving the company a distinct advantage over its foreign competitors.

The global expansion of these companies—from research partnerships with foreign universities through to the development of operational ‘smart city’ or ‘public security’ projects—raises important questions about the geostrategic, political and human rights implications of their work.

Users of the website will now find more than 26,000 datapoints that have helped to geo-locate 2,500+ points of overseas presence for the 23 companies and organisations. But it’s important to note that the presence of the companies’ products in overseas markets is far larger than the map can indicate.

Many of the companies’ relationships are business to business, and their products are integrated as part of other companies’ solutions. For example, iFlytek’s speech recognition software is used in the voice assistant in Huawei smartphones, and YITU provides its facial recognition and traffic monitoring software to Huawei’s smart cities solutions. So, while Huawei’s smart city solutions are mapped, the companies that provide certain technologies and component parts for smart cities can’t always be captured.

This illustrates a complex problem associated with data and privacy protection in ‘internet of things’ devices that is tackled in Dr Samantha Hoffman’s ASPI report Engineering global consent: the Chinese Communist Party’s data-driven power expansion.19 Companies can claim that they don’t misuse the data that their products collect, but those claims don’t always take into account how component-part manufacturers whose technologies are integrated into smart cities and public security services, for example, collect and use citizens’ data.

TikTok as a vector for censorship and surveillance

Unlike China’s first generation of social media tech giants, which stumbled in their international expansion,20 second-generation start-ups such as ByteDance are proving to be much more sure-footed. TikTok, a short-video app, is the company’s most successful foreign export, having grown a global audience of more than 700 million in just a few years.21 ByteDance achieved that meteoric growth, ironically enough, by ploughing US$1 billion into ads on the social platforms of its Western rivals Facebook, Facebook-owned Instagram and Snapchat.22

The app has managed to maintain its ‘stickiness’ for users—mostly teens—by virtue of the AI-powered advanced algorithm undergirding it. The remarkable success of the app enabled ByteDance to become the world’s most valuable start-up in October 2018 after it secured a US$3 billion investment round that gave it a jaw-dropping valuation of US$75 billion.23

TikTok has already attracted the ire of regulators around the world, including in Indonesia, India, the UK and the US, where the company made a $US5.7 million settlement with the Federal Trade Commission for violating the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act.

But beyond the expected regulatory missteps of a fast-growing social media platform, ByteDance is uniquely susceptible to other problems that come with its closeness to the censorship and surveillance apparatus of the CCP-led state. Beijing has demonstrated a propensity for controlling and shaping overseas Chinese-language media. The meteoric growth of TikTok now puts the CCP in a position where it can attempt to do the same on a largely non-Chinese speaking platform—with the help of an advanced AI-powered algorithm.

In September 2019, The Guardian revealed clear evidence of how ByteDance has been advancing Chinese foreign policy aims abroad through the app via censorship. The newspaper reported on leaked guidelines from TikTok laying out the company’s approach to content moderation.

The documents showed that TikTok moderators were instructed to ‘censor videos that mention Tiananmen Square, Tibetan independence, or the banned religious group Falun Gong.’24

Unlike Western social media platforms, which have traditionally taken a conservative approach to content moderation and tended to favour as much free speech as possible, TikTok has been heavy-handed, projecting Beijing’s political neuroses onto the politics of other countries. In the guidelines, as described by The Guardian, the app banned ‘criticism/attack towards policies, social rules of any country, such as constitutional monarchy, monarchy, parliamentary system, separation of powers, socialism system, etc.’ Many historical events in foreign countries were also swept up in the scope of the guidelines. In addition to a ban on mentioning the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, the May 1998 riots in Indonesia and the genocide in Cambodia were also deemed verboten.

TikTok has even barred criticism of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, as well as depictions of ‘non-Islamic gods’ and images of alcohol consumption and same-sex relationships—neither of which is in fact illegal in Turkey. Also prohibited is criticism of a list of ‘foreign leaders or sensitive figures’, including the past and present leaders of North Korea, US President Donald Trump, former South Korean President Park Geun-hye and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Despite this heavy-handed approach, a number of bad actors have been able to use the app to promote their agendas. On 23 October 2019, the Wall Street Journal reported that Islamic State has been using the app to share propaganda videos and has even uploaded clips of beheadings of prisoners.25 Motherboard also uncovered violent white supremacy and Nazism on the app in late 2018.26

ByteDance confirmed The Guardian’s report and the authenticity of the leaked content-moderation guidelines but said the guidelines were outdated and that it had updated its moderation policies.

Unconvinced, senior US lawmakers went on to request an investigation into TikTok on national security grounds.

In late October 2019, US Senator Marco Rubio appealed to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin to launch an investigation by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US into TikTok’s acquisition of US video-sharing platform Musical.ly,27 citing reports of censorship on the app, including a 15 September Washington Post article that provided evidence of TikTok’s censorship of reports on the Hong Kong protests.28

ByteDance said that the Chinese Government doesn’t order it to censor content on TikTok: ‘To be clear: we do not remove videos based on the presence of Hong Kong protest content,’ said a ByteDance spokesman cited by the New York Times.29 But a former content moderator for TikTok also told the Times that ‘managers in the United States had instructed moderators to hide videos that included any political messages or themes, not just those related to China’.

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, the former content moderator said that the policy was to, in the newspaper’s words, ‘allow such political posts to remain on users’ profile pages but to prevent them from being shared more widely in TikTok’s main video feed’—a practice known as ‘shadow banning’.

The concerns of other US Congress members extend from the app’s use of censorship to curate and shape information flows and export CCP media narratives to data privacy and the potential for the app to be used as a tool of surveillance in the service of the Chinese party-state. On 24 October, senators Chuck Schumer and Tom Cotton penned a letter asking Acting Director of National Intelligence Joseph Maguire to determine whether TikTok’s data collection practices pose a national security risk.30

David Carroll, an associate professor of media design at Parsons School of Design, discovered that TikTok’s privacy policy in late 2018 indicated that user data could be shared ‘with any member or affiliate of [its] group’ in China. TikTok confirmed to him that ‘data from TikTok users who joined the service before February 2019 may have been processed in China.’31

In November, regulators took action. Reuters reported that the US Government had launched a national security review of ByteDance’s US$1 billion acquisition of Musical.ly.32

Meiya Pico: from mobile data extraction to the Belt and Road’s ‘safety’ and security corridor

Inside China and at its borders, people are being asked to hand over their phones for police inspections. Within minutes, police can connect, extract and analyse phone and personal user data on the phone. In online chatter on Chinese platforms about the matter, people mostly express their fears of police discovering applications for ‘jumping the Great Firewall’, but police can extract more than just a list of installed applications. They can extract and access call and message logs; contact lists and calendars; location information; audio, video and documents; and application data.

In June 2019, Asia Society ChinaFile editor Muyi Xiao noticed multiple online reports on Chinese social media sites of Beijing and Shanghai police spot-checking people’s phones and installing a mobile app called ‘MFSocket’.33 She investigated further and found similar reports from Guangdong and Xinjiang from as early as 2016. One citizen reported that their employer had asked them and other colleagues to report to a police station, where, after they had their ID cards inspected and their photos and fingerprints taken, MFSocket was installed on their phones. In this particular case, the citizen had Google’s suite of apps installed (Google is available only outside China), and he was questioned about that.34 It isn’t clear whether these users were under suspicion for criminal activity, but one affected individual was reportedly going to the police station to update their ID, and another was riding their scooter and was stopped by police.35 Muyi Xiao’s investigations led her to the app’s developer—Meiya Pico, a prominent player in China’s digital forensics sector.

The MFSocket phone app is the client application for Meiya Pico’s mobile phone forensics suite.36

Once a person’s mobile phone is connected to the forensics terminal, the MFSocket app is pushed to the phone. When it’s installed, the operator is able to extract phone and personal user data from the phone, including contacts, messages, calendar events, call record data, location information, video, audio, a list of apps, system logs37 and almost 100 software applications.38

The functionality of MFSocket is neither unique nor suspicious; nor is it unusual for a digital forensics company to sell such software. What is of concern is the seemingly arbitrary nature of its use by police in China. It’s also not the only mobile data extraction app used in China. The Fengcai or BXAQ app,39 also known as ‘MobileHunter’,40 for example, has been installed onto the phones of foreign journalists crossing from Kyrgyzstan into Xinjiang. Similarly to MFSocket, it collects personal and phone data.41

Beyond China’s borders, Meiya Pico has provided training to Interpol42 and sells its forensics and mobile hacking equipment to the Russian military.43 Through financial support provided by China’s Ministry of Public Security, Meiya Pico also has a unique role in BRI projects. A report on Chinese information controls by the Open Technology Fund suggests that this could be part of a ‘safety corridor’ between China and Europe,44 linking safety and security products and services with foreign aid projects.45

Since 2013, Meiya Pico has been working with the Ministry of Public Security on BRI-focused foreign aid projects,46 constructing digital forensics laboratories in Central Asia and Southeast Asia,47 including in Vietnam48 and Sri Lanka.49 Meiya Pico claims to have provided, under the instruction of the ministry,50 more than 50 training courses to police forces in 30 countries51 as part of the BRI (Figure 1).52 For these projects, Meiya Pico reportedly sends professional and technical personnel to each location to conduct in-depth technical communication and exchanges.53 Chinese state media have reported that these projects enhance a country’s ability to fight cybercrime through technical and equipment assistance and support.54

Figure 1: Meiya Pico and BRI projects

Source: Meiya Pico, Belt and Road.

CloudWalk and data colonialism in Zimbabwe

The draconian techno-surveillance system that China is perfecting in Xinjiang and steadily expanding to the rest of the country is increasingly seen as an alternative model by non-democratic regimes around the world. In the first Mapping China’s tech giants report, we examined how Chinese technology companies are closely entwined with the CCP’s support for Zimbabwe’s authoritarian regime. From the country’s telco infrastructure through to social media and cybercrime laws, the PRC’s influence is pervasive.

In March 2018, the Zimbabwean Government took this approach to a new level when it signed an agreement with CloudWalk Technology to build a national facial recognition database and monitoring system as part of China’s BRI program of international infrastructure deals.55 The agreement was reached between a ‘special adviser to Zimbabwe’s Presidential Office’, the Minister of Science and Technology in Nansha district of Guangzhou and CloudWalk executives, according to a Science Daily (科技日报) report.56 Under the deal, Zimbabwe will send biometric data on millions of its citizens to China to assist in the development of facial recognition algorithms that work with different ethnicities and will therefore expand the export market for China’s product—an arrangement that had no input from ordinary Zimbabwean citizens. In exchange, Zimbabwe’s authoritarian government will get access to CloudWalk’s technology and the opportunity to copy China’s digitally enabled authoritarian system.

Former Zimbabwean Ambassador to China Christopher Mutsvangwa told The Herald, a Zimbabwean newspaper, that CloudWalk had donated facial recognition terminals to the country and that the terminals are already being installed at every border post and point of entry around the southern African nation: ‘China has proved to be our all-weather friend and this time around, we have approached them to spearhead our AI revolution in Zimbabwe.’ 57

The arrangement is paradigmatic of a new form of colonialism called ‘data colonialism’, in which raw information is harvested from developing countries for the commercial and strategic benefit of richer, more powerful nations that hold AI supremacy.58 Writing in the New York Times, Kai-Fu Lee, the former Google China head and doyen of China’s AI industry, outlined how these kinds of colonial arrangements are set to ‘reshape today’s geopolitical alliances’:59

[I]f most countries will not be able to tax ultra-profitable AI companies to subsidize their workers, what options will they have? I foresee only one: Unless they wish to plunge their people into poverty, they will be forced to negotiate with whichever country supplies most of their AI software—China or the United States—to essentially become that country’s economic dependent, taking in welfare subsidies in exchange for letting the ‘parent’ nation’s AI companies continue to profit from the dependent country’s users. Such economic arrangements would reshape today’s geopolitical alliances.

The CloudWalk–Zimbabwe deal, Science Daily notes, is a first for the Chinese AI industry in Africa and serves a clear geostrategic aim: ‘[It] will enable China’s artificial intelligence technology to serve the economic development of countries along the “belt and road initiative” route.’

The arrangement will not only help bring the Zimbabwean regime’s authoritarian practices further into the digital age, but will also enable the PRC—through state-backed and other nominally private companies—to export those means for other countries to use to surveil, repress and manipulate their populations.

Facial recognition technology is notoriously bad at detecting people with dark skin, making the data that the Zimbabwean Government is trading with CloudWalk highly prized.60 By improving its facial recognition systems for people with dark skin, CloudWalk is effectively opening up whole new markets around the world for its technology, while Zimbabwe perceives CloudWalk as ‘donating’ its technology to the country.

In exchange for the private biometric details of the Zimbabwean citizenry, CloudWalk’s technology will be deployed in the country’s financial industry, airports, bus stations, railway stations and, as the Science Daily puts it, ‘any other locations requiring face recognition to effectively maintain public security’.

According to The Herald, Zimbabwe signed another agreement with CloudWalk in April 2019, under which the Chinese firm will provide facial recognition for smart financial service networks, as well as intelligent security applications at airports and railway and bus stations. The new deal, according to the paper, was reached during a visit to China by Zimbabwean President Mnangagwa and forms part of China’s BRI in Africa.61

‘The Zimbabwean Government did not come to Guangzhou purely for AI or facial recognition technologies; rather it had a comprehensive package plan for such areas as infrastructure, technology and biology,’ CloudWalk CEO Yao Zhiqiang said at the time, according to the paper.

BeiDou: China’s satellite and space race

Unlike other entities featured in this report, the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BeiDou) isn’t a company; rather, it’s a centrally controlled satellite constellation and associated service that provides positioning, navigation and timing information. It also presents itself as a completely functional and improved alternative to the US-controlled Global Positioning System (GPS).

The development of BeiDou began after the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1996, when missile tests by the Chinese military were ineffective due to suspected US-directed disruption of the GPS. After that failure, the ‘Chinese military decided, no matter how much it would cost, [that China] had to build its own independent satellite navigation system.’62

The first generation of the system consisted of three satellites that provided rudimentary positioning services to users in China. However, in 2013, China reached its first agreements to export the service to other countries. Since then, BeiDou has upped the tempo of its global expansion and engagement.

For increased accuracy, positional satellites such as the BeiDou constellations need to precisely determine their orbital position. At this fine scale, satellite orbits aren’t regular across the globe, and modelling them within the millisecond relies on a global network of reference stations and onboard atomic clocks. The reference stations share data containing information on how long signals take to reach the receiver from the satellite, and then precise orbital determination can be more accurately modelled by trilaterating (similar to triangulating – using distances rather than angles) those signals (Figure 2). A wide geographical spread of reference stations allows the orbit to be precisely determined over a larger area.63 By having stations or receivers overseas, including in Australia, for example, BeiDou is able to more precisely determine post-processing adjustments over Australia, and thereby provide more precise positional data to an end user.

Figure 2: An infographic explaining how base stations can improve GNSS positional accuracy

Source: An introduction to GNSS, Hexagon.

In 2013, BeiDou signed an agreement with Brunei to supply the country with the technology for military and civilian use at a heavily subsidised price.64 Following Chinese Premier Li Keqiang’s 2013 visit to Islamabad, Pakistan became the first country in the world to sign an official cooperation agreement with the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System in both the military and civilian sectors.

Pakistan was granted access to the system’s post-processed data service, which provides far more precise location services and accompanying encryption services.65 These additional features allow for more precise guidance for missiles, ships and aircraft.66 In recent years agreements have also been reached with other countries including the United States and Russia to establish interoperability between different GNSS satellite constellations.

In the run-up to the 3rd generation of BeiDou’s satellite constellation, the service began to more aggressively pursue internationalisation. Agreements with countries in South and Southeast Asia were signed, providing access to BeiDou services and allowing BeiDou to construct permanent reference stations across the region and increase its positional accuracy outside China’s borders. In 2014, it was announced that China was planning to construct 220 reference stations in Thailand and a network of 1,000 across Southeast Asia.67 These newer stations improve the precise post-processing accuracy of the satellite signals, which in turn increases the precision of signals received by end users.68

In 2014, China Satellite Navigation System Management Office and Geoscience Australia established a similar agreement, but on a smaller scale. They met in Beijing with representatives of Wuhan University. The two sides reportedly agreed to establish a formal cooperation mechanism.69

Wuhan University was to provide Geoscience Australia with three continuously operating reference stations equipped with satellite signal receivers constructed by China Electronic Technology Group (CETC). CETC is one of China’s largest state-owned defence companies and was covered in the original dataset of Mapping China’s Technology Giants.70 By using CETC-constructed receivers, GA was provided access to additional signals that were unavailable to commercial off-the-shelf receivers. GA manages the communications of these sites, and also receives access to the global Wuhan University’s network of overseas tracking data.71

BeiDou’s presence in Australia has previously attracted academic and media scrutiny. Professor Anne-Marie Brady has been critical of Australia’s engagement with BeiDou because of its role in guiding China’s military technologies:72

Australia is playing a small part in helping China to get a GPS system as effective as the US system. China is aiming to have a better one than the US has by 2020, and so is Russia. They need ground stations to coordinate their satellites and they need them in the Pacific. Their first ground station in the Pacific region was built in Perth.

The three BeiDou ground facilities in Australia are at Yarragadee Station (Western Australia; the first one built), Mount Stromlo (Australian Capital Territory) and Katherine (Northern Territory) and are operated by Geoscience Australia. They were built in 2016 and have been operating for over three years.73 No data is sent directly from these (or any) receivers back to the BeiDou satellites, and detailed positional and signal data is provided publicly. These data streams are widely used by industry and civilian end-users.

The stations are a small part of Australia’s GNSS network, which then publicly provides precise positional and signal data. But it’s worth noting that Wuhan University has close links to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and has been previously accused by the US and Taiwanese Governments of carrying out cyberattacks.74

Foreign investment

The detention of an estimated 1.5 million members of ethnic minority groups,75 chiefly Uyghur, in so-called re-education camps in China’s far western region of Xinjiang is a human rights violation on a massive scale.76 For Chinese security companies, however, it is a win.

Many of the AI and surveillance companies added to our Mapping China’s Technology Giants project have capitalised on China’s surge in security spending, particularly in Xinjiang, in recent years.

Spending on security-related construction in Xinjiang tripled in 2017, according to an analysis of government expenditure by Adrian Zenz for the Jamestown Foundation.77

For Chinese security, AI and surveillance companies, Xinjiang has become, as Charles Rollet put it in Foreign Policy, ‘both a lucrative market and a laboratory to test the latest gadgetry’.78 The projects there, he notes, ‘include not only security cameras but also video analytics hubs, intelligent monitoring systems, big data centres, police checkpoints, and even drones.’

But China’s burgeoning surveillance state isn’t limited to Xinjiang. The Ministry of Public Security has ploughed billions of dollars into two government plans, called Skynet project (天网工程)79 and Sharp Eyes project (雪亮工程),80 that aim to comprehensively surveil China’s 1.4 billion people by 2020 through a video camera network using facial recognition technology.

China will add 400 million security cameras through 2020, according to Morgan Stanley, making investing in companies such as Hikvision and Dahua—which have received government contracts totalling more than US$1 billion81—extremely enticing for investors seeking high returns. Crucially, the gold rush hasn’t been limited to Chinese firms and investors.

Foreign investors, either passively or actively, are also profiting from China’s domestic security and surveillance spending binge. Investment funds controlling around US$1.9 trillion that measure their performance against MSCI’s benchmark Emerging Markets Index funnel capital into companies such as Hikvision82, Dahua83 and iFlytek,84 which have profited from the development of Xinjiang detention camps.

The market valuation of SenseTime, one of a few companies handpicked by the party-state to lead the way in China’s AI development, soared in 2018 on the back of increased government funding for its national facial recognition surveillance system.

Those massive government contracts have helped SenseTime attract top venture capital and private equity firms as well as strategic investors around the world, including Japanese tech conglomerate Softbank Group’s Saudi-backed Vision Fund. US venture fund IDG Capital supplied ‘tens of millions of dollars’ in initial funding to the company in August 2014.85

Other major shareholders include e-commerce giant Alibaba Group Holding Ltd, London-based Fidelity International (a subsidiary of Boston-based Fidelity Investments), Singaporean state investment firm Temasek Holdings, US private equity firms Silver Lake Partners and Tiger Global Management, and the venture capital arm of US telco Qualcomm.

More than 17 US universities and public pension plans have put money into vehicles run by some of these venture capital funds, according to an Australian Financial Review report citing historical PitchBook data.86

SenseTime rival, Megvii Technology, has also benefited from foreign investment, including from a Macquarie Group fund that sunk $US30 million ($44 million) into the facial recognition start-up.87

Macquarie declined to comment when questioned about the investment by the Australian Financial Review. Other firms such as Goldman Sachs Group Inc, have stated they’re reviewing their involvement in Megvii’s planned initial public offering after the U.S. government placed it on the US Entity List for alleged complicity in Beijing’s human rights abuses in China.88

Two of America’s biggest public pension funds—the California State Teachers’ Retirement System and the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System—own stakes in Hikvision, as the Financial Times reported in March 2019.89 Since at least 2018, Meiya Pico shares have been included in the FTSE Russell Global Equity Index.90

Even if these companies aren’t listed on foreign bourses or are receiving money from foreign venture capital funds, they might still be getting investments from companies such as the BATs—Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent—that are traded on US stock exchanges.91

But, more often than not, the investments are made directly and wittingly by active funds that are seeking to maximise profits off the back of the boom in surveillance technologies used across China. To put it plainly, Western capital markets have funded mass detentions and an increasingly sophisticated repressive apparatus in China.

Some funds that have done their human rights and national security due diligence have started to divest themselves of some of these companies. At least seven US equity funds have divested from Hikvision, for instance.92 But many have not.

‘A lot of investors talk about ethical investing but when it comes to Hikvision and Xinjiang they are happy to fill their boots,’ one fund manager who sold out of Hikvision told the Financial Times in March 2019. ‘It is pretty hypocritical.’93

All roads lead to Xinjiang

In November 2019, internal Communist Party documents—obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ)—provided documentary evidence of how authorities in Xinjiang are using data and artificial intelligence to pioneer a new form of social control.94 The documents showed how authorities are using a data management system called the Integrated Joint Operation Platform (IJOP)—previously reported on by Human Rights Watch—to predictively identify those suspected of harbouring extremist views and criminal intent.95 Among the documents, a bulletin published on 25 June 2017, reveals how the IJOP system detected about 24,412 “suspicious” people in southern Xinjiang during one particular week. Of those people, 15,683 were sent to “education and training” — a euphemism for detention camps—and 706 were “criminally detained”.96

A month before this leak, in October 2019, the US Government added many of the AI and surveillance companies in this dataset—including Dahua Technology, iFlytek, Megvii Technology, SenseTime, Xiamen Meiya Pico Information Co. Ltd, Yitu Technologies and Hikvision97—to the US Entity List because of their roles in human rights violations in Xinjiang.98

However, Chinese tech companies’ activities in Xinjiang go beyond surveillance and extend to areas like propaganda and other coercive measures.

For example, we have found that TikTok’s parent company ByteDance—which is not on the US entity list for human rights violations in Xinjiang—collaborates with public security bureaus across China, including in Xinjiang where it plays an active role in disseminating the party-state’s propaganda on Xinjiang.

Xinjiang Internet Police reportedly “arrived” on Douyin—a ByteDance and video-sharing app—and built a “new public security and Internet social governance model” in 2018.99 In April 2019, the Ministry of Public Security’s Press and Publicity Bureau signed a strategic cooperation agreement with ByteDance to promote the “influence and credibility” of police departments nationwide.100 Under the agreement, all levels and divisions of police units from the Ministry of Public Security to county-level traffic police would have their own Douyin account to disseminate propaganda. The agreement also reportedly says ByteDance would increase its offline cooperation with the police department, however it is unclear what this offline cooperation is.

Tech companies have been piling into Xinjiang since the early 2010s. Huawei has been working for the Karamay Police Department on cloud computing projects since 2011,101 despite its debunked claims to work only with third parties.102 ZTE held its first Smart Cities Forum in Urumqi in 2013,103 and its ‘safe city’ solution has been largely used in surveilance and policing.104 In 2010, iFlytek set up a subsidiary in Xinjiang and a laboratory to develop speech recognition technology,105 especially in minority languages—technologies that are now used by the Xinjiang Government to track and identify minority populations.106

A surveillance industry boom was born out of the central government’s 2015 policy to prioritise ‘stability’ in Xinjiang107 and the national implementation of the Sharp Eyes surveillance project from 2015 to 2020.108 As of late 2017, 1,013 local security companies were working in Xinjiang;109 that figure excludes some of the largest companies operating in the region, such as Dahua and Hikvision, which had already won multimillion-dollar bids to build systems to surveil streets and mosques.110

Also in 2017, even with the central government halting some of the popular ‘PPP’ projects (public– private partnerships that channel private money into public infrastructure projects) that were debt hazards111 and tech companies becoming more cautious about investing in those projects, Xinjiang was an exception for about a year. Tech companies continued to hunt for opportunities in Xinjiang because funding for surveillance-related PPP projects in Xinjiang comes directly from defence and counterterrorism expenditure.112 However, in 2018, the debt crackdown eventually reached Xinjiang and a number of PPP projects there were also suspended. 113

A significant policy that encourages technology companies to profit from the situation in Xinjiang is the renewed ‘Xinjiang Aid’ scheme (援疆政策). Dating from the 1980s, these policies channel funds from other provincial governments to Xinjiang. Since the mass detentions in 2017 this scheme has encouraged companies in other provinces to open subsidiaries or factories in Xinjiang—factories that former detainees are forced to work in.114

A company can contribute to the Xinjiang Aid program, and the broader situation in the region, in many different ways. In 2014, for example, Alibaba began to provide cloud computing technologies for the Xinjiang Government in areas of policing and counterterrorism.115 In 2018, as part of Zhejiang Province’s Xinjiang Aid efforts, Alibaba was set to open large numbers of e-commerce service stations in Xinjiang, selling clothes and electronics.116 There’s no direct evidence that suggests Alibaba sells products sourced from forced labour. But clothing companies that have recently opened up factories in Xinjiang, because of favourable polices and an abundance of local labour—which can include forced labour117—have relied on Alibaba’s platforms to sell clothes to China, North America, Europe and the Middle East.118

Most of ByteDance’s activities in Xinjiang fall under the “Xinjiang Aid” initiative and the company’s cooperation with Xinjiang authorities is focused on Hotan, a part of Xinjiang that has been the target of some of the most severe repression. The area is referred to by the party-state as the most “backward and resistant”.119 According to satellite imagery analysis conducted by ASPI, there are approximately a dozen suspected detention facilities in the outskirts of Hotan.120 The city has seen an aggressive campaign of cemetery, mosque and traditional housing demolition since November 2018, which continues today.

In November 2019, Beijing Radio and Television Bureau announced its “Xinjiang Aid” measures in Hotan, to “propagate and showcase Hotan’s new image”—after more than two years of mass detention and close surveillance of ethnic minorities had taken place there. These measures include guiding and helping local Xinjiang authorities and media outlets to use ByteDance’s news aggregation app for Jinri Toutiao (Today’s Headlines) and video-sharing app Douyin to gain traction online.121 A Tianjin Daily article reported this April that after listening to talks by representatives from ByteDance’s Jinri Toutiao division, Hotan Propaganda Bureau official Zhou Nengwen (周能文) said he was excited to use the Douyin platform to promote Hotan’s products and image.122

Technology companies actively support state projects, even when those projects have nothing to do with tech. Also under the Xinjiang Aid umbrella, telecom companies such as China Unicom send their ‘most politically reliable’ employees to Xinjiang123 and deploy fanghuiju (访惠聚) units to villages in Xinjiang. ‘Fanghuiju’ is a government initiative that sends cadres from government agencies, state-owned enterprises and public institutions to regularly visit and surveil people.124

The China Unicom fanghuiju units were reportedly tasked with changing the villages, including villagers’ thoughts that are religious or go against CCP doctrines.125 Adding some of China’s more well-known technology and surveillance companies to the US Entity List was largely symbolic—after Huawei, Dahua and Hikvision were blacklisted in the US, Uniview’s president told reporters that, at a time when ‘leading Chinese technology companies are facing tough scrutiny overseas’, companies such as Uniview had the opportunity to grow and pursue their overseas strategies.126

Unfortunately, it’s extremely difficult for international authorities to sanction the circa 1,000 homegrown local Xinjiang security companies. However, as companies such as Huawei seek to expand overseas, foreign governments can play a more active role in rejecting those that participate in the Chinese Government’s repressive Xinjiang policies.

For example, the timeline of Huawei’s Xinjiang activities should be taken into consideration during debates about Huawei and 5G technologies. Huawei’s work in Xinjiang is extensive and includes working directly with the Chinese Government’s public security bureaus in the region. The announcement of one Huawei public security project in Xinjiang—made in 2018 through a government website in Urumqi127—quoted a Huawei director as saying, ‘Together with the Public Security Bureau, Huawei will unlock a new era of smart policing and help build a safer, smarter society.’128 In fact, some of Huawei’s promoted ‘success cases’ are Public Security Bureau projects in Xinjiang, such as the Modular Data Center for the Public Security Bureau of Aksu Prefecture in Xinjiang.129 Huawei also provides police in Xinjiang with technical support to help ‘meet the digitization requirements of the public security industry’.130

In May 2019, Huawei signed a strategic agreement with the state-owned media group Xinjiang Broadcasting and Television Network Co. Ltd at Huawei’s headquarters in Shenzhen. The agreement, which aims at maintaining social stability and creating positive public opinion, covered areas including internet infrastructure, smart cities and 5G.131

In 2018, when the Xinjiang Public Security Department and Huawei signed the agreement to establish an ‘intelligent security industry’ innovation lab in Urumqi. Fan Lixin, a Public Security Department official, said at the signing ceremony that Huawei had been supplying reliable technical support for the department.132 In 2016, Xinjiang’s provincial government signed a partnership agreement with Huawei.133 The two sides agreed to jointly develop cloud computing and big-data industries in Xinjiang. As mentioned above, Huawei began to work in cloud computing in Karamay (a Huawei cloud-computing ‘model city’ in Xinjiang)134 as early as 2011 in several sectors, including public security video surveillance.

In 2014, Huawei participated in an anti-terrorism BRI-themed conference in Urumqi as ‘an important participant of’ a program called ‘Safe Xinjiang’—code for a police surveillance system. Huawei was said to have built the police surveillance systems in Karamay and Kashgar prefectures and was praised by the head of Xinjiang provincial police department for its contributions in the Safe Xinjiang program.

Huawei was reportedly able to process and analyse footage quickly and conduct precise searches in the footage databases (for example, of the colour of cars or people and the direction of their movements) to help solve criminal cases.135

Since mass detentions began in Xinjiang over two years ago, state-affiliated technology companies such as those covered in this report have greatly expanded their remit and become a central part of the surveillance state in Xinjiang. Xinjiang’s crackdown on religious and ethnic minorities has been completed across the region. It has used and continues to use several different mechanisms of coercive control, such as arbitrary detention, coerced labour practices136 and at-home forced political indoctrination. Technology companies are intrinsically linked with many of those efforts, as the state’s crackdown offers ample opportunities for incentivised expansion and profitability.137

Conclusion

The aim of this report is to promote a more informed debate about the growth of China’s tech giants and to highlight areas where their expansion raises political, geostrategic, ethical and human rights concerns.

The Chinese tech companies in this report enjoy a highly favourable regulatory environment and are unencumbered by privacy and human rights concerns. Many are engaged in deeply unethical behaviour in Xinjiang, where their work directly supports and enables mass human rights abuses.

The CCP’s own policies and official statements make it clear that it perceives the expansion of Chinese technology companies as a crucial component of its wider project of ideological and geopolitical expansion, and that they are not purely commercial actors.138 The PRC’s suite of intelligence and security laws which can compel individuals and entities to participate in intelligence work139, and the CCP committees embedded within the tech companies (Chinese media has reported Huawei has more than 300 for example140) highlight the inextricable links between industry and the Chinese party-state.

These close ties make it difficult for them to be politically neutral actors. For western governments and corporations, developing risk mitigation strategies is essential, particularly when it comes to critical technology areas.

Some of these companies lead the world in cutting-edge technology development, particularly in the AI and surveillance sectors. But this technology development is focused on servicing authoritarian needs, and as these companies go global (an expansion often funded by PRC loans and aid) this technology is going global as well. This alone should give Western policymakers pause.

Increasing technological competition has the potential to deliver many benefits across the spectrum, but the benefits will not always accrue without good policy. If the West is going to continue to support the global expansion of these companies, it should, at a minimum, better understand the spectrum of policy risks and hold these companies to the same levels of accountability and transparency as it does its own corporations.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr Samantha Hoffman and Nathan Ruser for their research contributions to this report and to the broader Mapping China’s Technology Giants project. Thank you to Fergus Hanson, Michael Shoebridge and anonymous peer reviewers for their valuable feedback on report drafts. And thank you to Cheryl Yu and Ed Moore for their research and data collection efforts.

What is ASPI?

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non‑partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally.

ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre

ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre (ICPC) is a leading voice in global debates on cyber and emerging technologies and their impact on broader strategic policy. The ICPC informs public debate and supports sound public policy by producing original empirical research, bringing together researchers with diverse expertise, often working together in teams. To develop capability in Australia and our region, the ICPC has a capacity building team that conducts workshops, training programs and large-scale exercises both in Australia and overseas for both the public and private sectors. The ICPC enriches the national debate on cyber and strategic policy by running an

international visits program that brings leading experts to Australia.

Important disclaimer

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in relation to the subject matter covered. It is provided with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering any form of professional or other advice or services. No person should rely on the contents of this publication without first obtaining advice from a qualified professional.

© The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Limited 2019

This publication is subject to copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. Notwithstanding the above, educational institutions (including schools, independent colleges, universities and TAFEs) are granted permission to make copies of copyrighted works strictly for educational purposes without explicit permission from ASPI and free of charge.

- ‘Chinese police use app to spy on citizens’ smartphones’, Financial Times, 3 July 2019, online. ↩︎

- Mapping China’s Tech Giants, ‘Explore a company’, online. ↩︎

- China Eximbank is wholly owned by the Chinese Government. More detail can be found in Danielle Cave, Samantha Hoffman, Alex Joske, Mapping China’s technology giants, ASPI, Canberra, 2019, 10, online. ↩︎

- Lucas Niewenhuis, ‘1.5 million Muslims are in China’s camps—scholar’, SupChina, 13 March 2019, online. ↩︎

- Mapping China’s Tech Giants, ‘Welcome to Mapping China’s Tech Giants’, online. ↩︎

- Mapping China’s Tech Giants, ‘How to use this tool’, online. ↩︎

- Mapping China’s Tech Giants, ‘Glossary’, online. ↩︎

- Science and Technology Committee, ‘Oral evidence: UK telecommunications infrastructure’, HC 2200, House of Commons, 10 June 2019, online. ↩︎

Guo, also known as Miles Kwok, fled to the United States in 2017 following the arrest of one of his associates, former Ministry of State Security vice minister Ma Jian. Guo has made highly public allegations of corruption against senior members of the Chinese government. The Chinese government in turn accused Guo of corruption, prompting an

Guo, also known as Miles Kwok, fled to the United States in 2017 following the arrest of one of his associates, former Ministry of State Security vice minister Ma Jian. Guo has made highly public allegations of corruption against senior members of the Chinese government. The Chinese government in turn accused Guo of corruption, prompting an

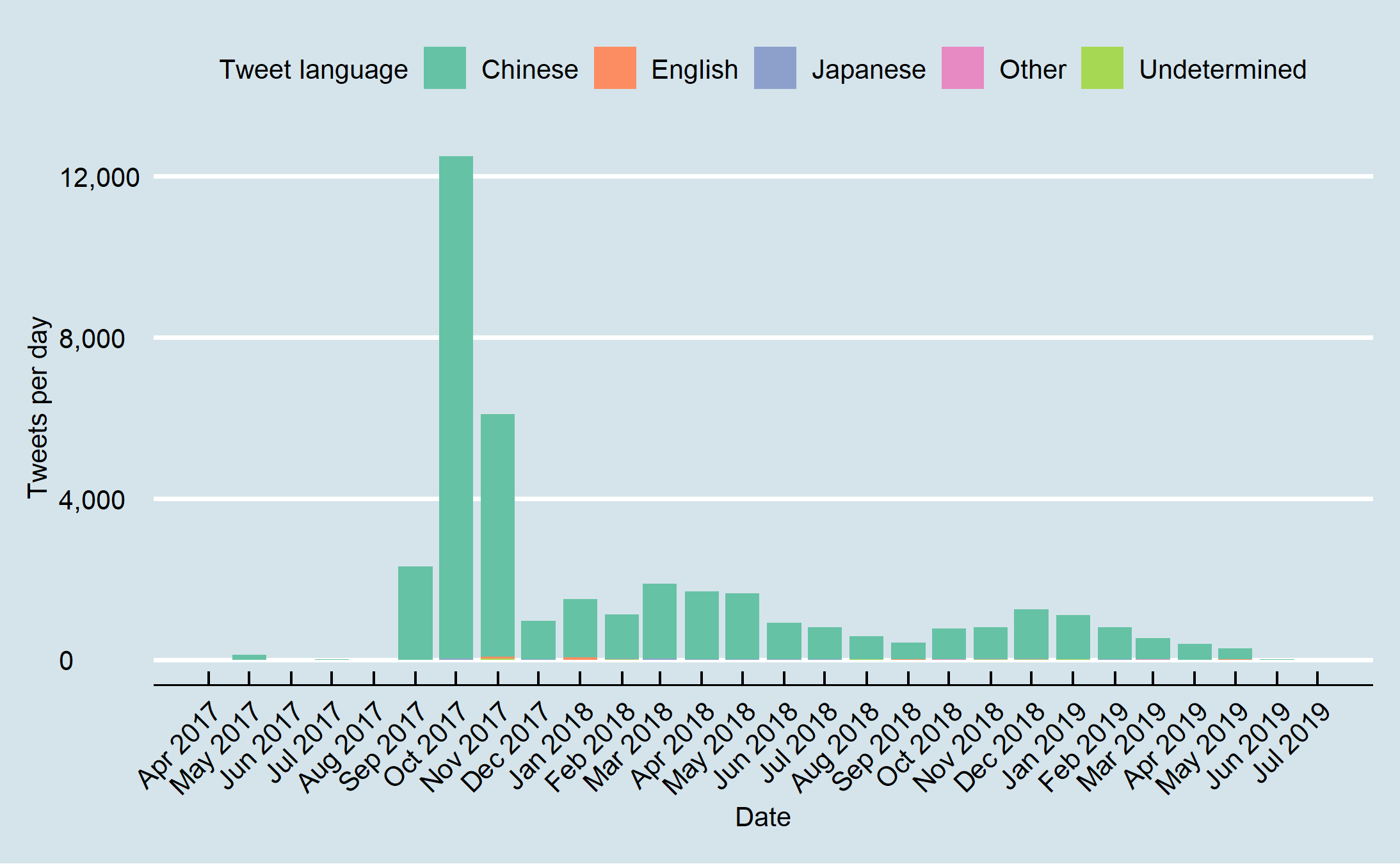

Figure 11: Percent Chinese language tweets per day from Jan 2017 onwards.

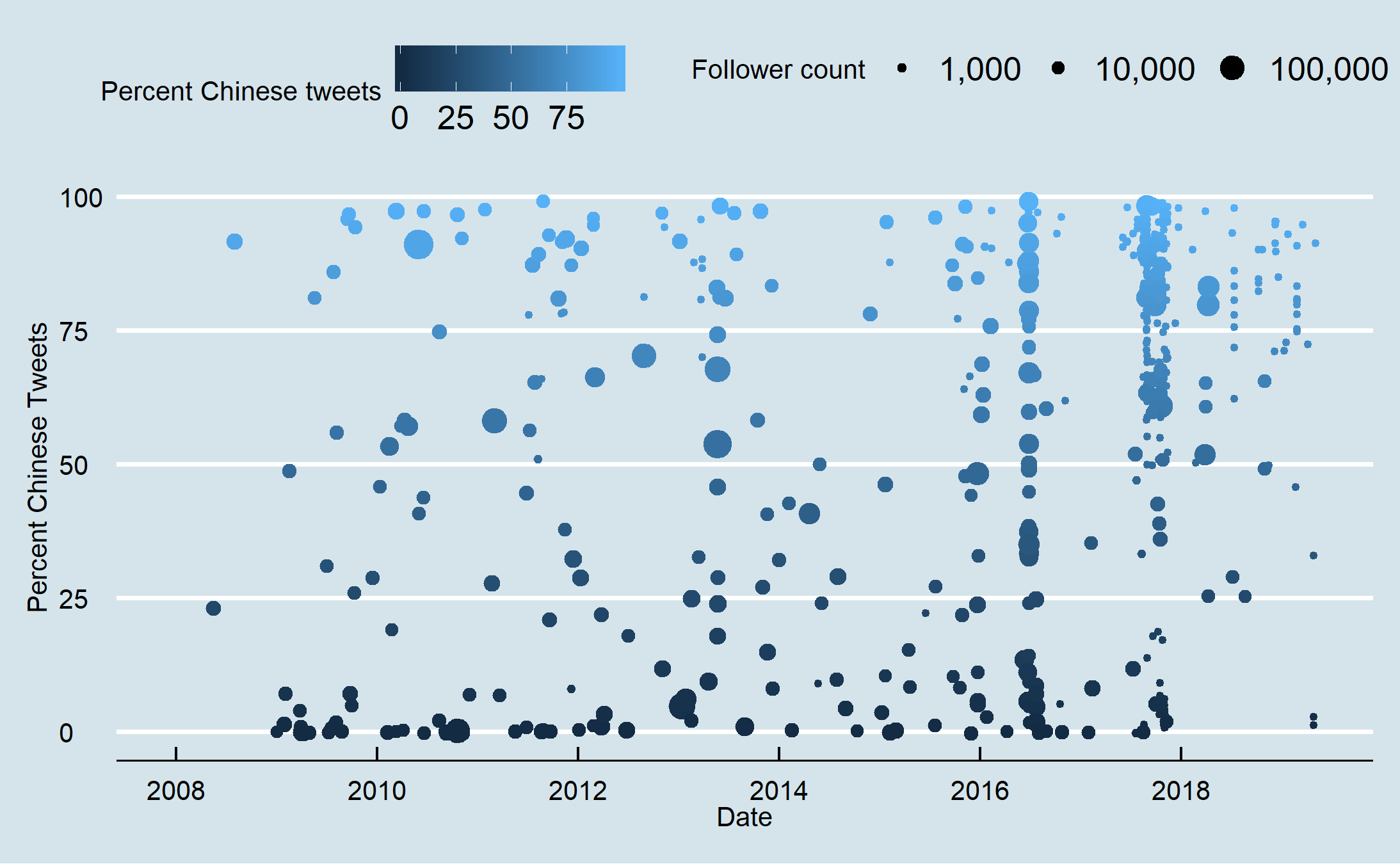

Figure 11: Percent Chinese language tweets per day from Jan 2017 onwards. Figure 12: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from 2008 to July 2019.

Figure 12: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from 2008 to July 2019. Figure 13: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from April 2016 to July 2019.

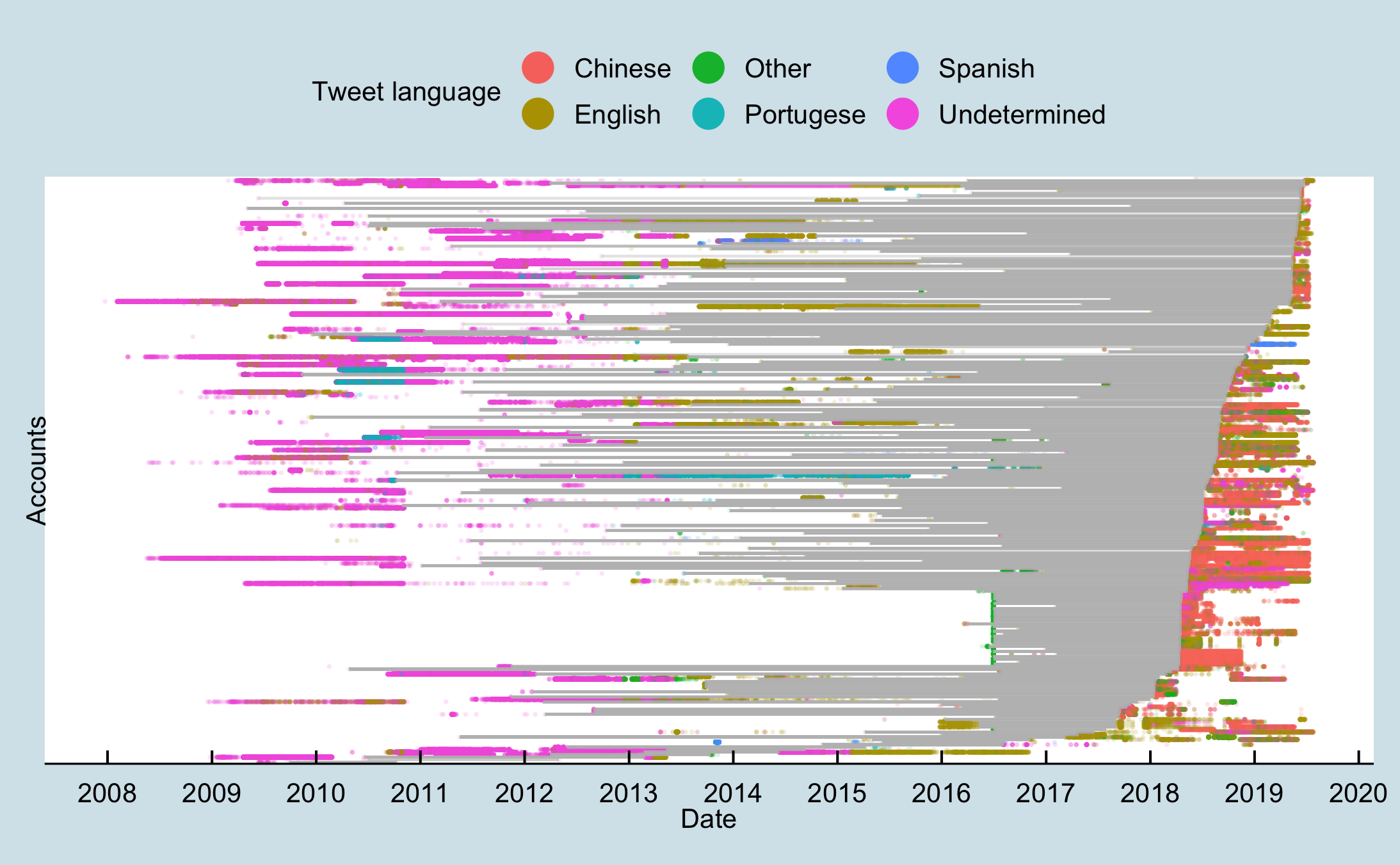

Figure 13: Account creation day by percent Chinese tweets and follower size from April 2016 to July 2019. Figure 14: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets. More than year-long gaps between tweets are represented by grey lines.

Figure 14: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets. More than year-long gaps between tweets are represented by grey lines. Figure 15: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets that were created between June and August 2016.

Figure 15: Tweets over time as represented as dots coloured by tweet language for accounts with a greater than one-year gap between tweets that were created between June and August 2016.