Working with the grain: history and Britain’s South Pacific tilt

‘The Pacific is inconstant and uncertain like the soul of man. Sometimes it is grey like the English Channel off Beachy Head, with a heavy swell, and sometimes it is rough, capped with white crests, and boisterous. It is not so often that it is calm and blue. Then, indeed, the blue is arrogant. The sun shines fiercely from an unclouded sky. The trade wind gets into your blood and you are filled with an impatience for the unknown.’

Somerset Maugham, The Trembling of a Leaf: Little Stories of the South Sea Islands, 1921

‘There is a gulf of difference between viewing the Pacific as “islands in a far sea” and as “a sea of islands”. The first emphasises dry surfaces in a vast ocean far from the centres of power. When you focus this way, you stress the smallness and remoteness of the islands.’

Epeli Hau’ofa, Our sea of islands, 1994

‘I wish I could tell you about the South Pacific. The way it actually was. The endless ocean. The infinite specks of coral we called islands. Coconut palms nodding gracefully towards the ocean. Reefs upon which waves broke into spray, and inner lagoons, lovely beyond description. I wish I could tell you about the sweating jungle, the full moon rising beyond the volcanoes, and the waiting. The waiting. The timeless, repetitive waiting.’

James A.Michener, Tales of the South Pacific, 1947

The uncertain and unknown South Pacific is from Somerset Maugham as the bard of British colonialism at its highest moment—the rulers were still anxious about what they ruled.

Epeli Hau’ofa, one of the great thinkers of the modern South Pacific, dismantles the European view of the islands as ‘tiny, isolated dots in a vast ocean’ that could be divided and allocated by ‘imaginary lines across the sea’. The alternate understanding of a sea of islands makes Hau’ofa the intellectual father of today’s vision of the Blue Pacific continent.

The description of the sunny, peaceful islands opens Michener’s vivid account of the Pacific war, the most destructive of the powerplays that have surged through the South Pacific for 250 years. The life of the islands has been shaped by great power ambitions and machinations. Today’s powerplay brings Britain back to the South Pacific.

For the 50 years since the independence era in islands, Britain like the United States left Australia and New Zealand to worry about the security of Melanesia and Polynesia. As Washington advised in 1977, Canberra and Wellington should ‘shoulder the main burden’.

The China challenge means the US and Britain must turn back to the region as one element in the Indo-Pacific age.

The global balance will be set in the Indo-Pacific, and that slowly tilts British attention to the South Pacific it once dominated. A new era of powerplay revives old habits.

The British invasion of the islands can be dated from April 1769, when James Cook sailed the Endeavour into Matavai Bay in Tahiti. The great Australian journalist Alan Moorehead called it the start of The Fatal Impact, subtitling his book, ‘An account of the invasion of the South Pacific’.

From that time, the Pacific has always been a stage for plays by great powers. Following Cook, ‘British activities in the Pacific stemmed from imperial ambitions that at one time or another brought them into conflict with every other nation that sought a place in the sun,’ C. Hartley Grattan wrote in his account of the 18th and 19th century colonial contests in the Pacific involving Britain, Spain, France, Holland, Germany, Russia and the United States.

The competition was fueled by commerce, colonial contest, and the desire for Christian converts.

‘During most of the 19th century,’ Donald Denoon noted, ‘the British Navy was the main over-arching authority in the Pacific, exercising “informal empire” at a time when Britain was committed to free trade and reluctant to incur the costs of colonial administration.’ In the 20th century, Britain shifted from informal to formal empire. Britain played a huge role in shaping the region’s religious, cultural and institutional life.

All that history stands in contrast to Britain’s minimal to non-existent security role in the South Pacific for the last 50 years.

When Britain’s foreign secretary visited the South Pacific after a G7 meeting in Japan in April 2023, the House of Commons foreign policy committee noted with ‘regret that no Foreign Secretary had visited most of these countries since the 1970s’.

The strategic absence is a strange lacuna in the rich British legacy in the life of South Pacific: Christianity, Westminster democracy and law, and English as the regional language.

In his 2001 history of the South Pacific, Ron Crocombe pointed to Britain’s reduced presence but lasting effect: ‘Having been the main superpower in relation to Oceania for nearly 200 years, Britain is now a minor player. Its historic role remains significant through English language and culture, extensive investments, aid, media, education, diplomatic presence, and many British people working in governments, business, NGOs, and missions.’

The British monarch is the head of state for Australia, Cook Islands, New Zealand, Niue, Norfolk Island, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Tokelau and Tuvalu. Britain still has defence and foreign policy responsibility for its sole overseas territory in the region, the Pitcairn Islands.

Britain bequeathed much, but when it lowered the Union Jack and said it was off, it really left.

Contrast Britain’s departure with the actions of France, Australia and New Zealand in Melanesia and Polynesia, and the US in Micronesia. As Greg Fry comments: ‘For all except the United Kingdom (which retained only a token interest after withdrawing from its last major Pacific colony [New Hebrides, now Vanuatu] in 1980), strategic interest heightened as the region became more involved in Cold War competition.’

The United States and France are the external powers that have stayed and built their security roles. Australia and New Zealand are the outsiders that have become insiders, marrying history to geography to cement new forms of partnership with island states.

For Britain, part of decolonisation was military departure. During the exit from the South Pacific in the 1960s and ‘70s, Britain was pulling back its military from East of Suez. Dean Acheson offered an eloquent but controversial diagnosis in 1962: ‘Great Britain has lost an empire and has not yet found a role.’ As an Anglophile, Acheson enjoyed unloading epigrams on the Brits (and the Australians), as evidenced by his observation that Sydney was ‘rather like some English food, sustaining but uninteresting’.

The hard-nosed version of dispensing with empire is the judgement that Britain could no longer afford it, as Harold Wilson acknowledged by devaluing sterling by 14% and a few weeks later, in January 1968, announcing the withdrawal from military bases ‘east of Aden’.

The focus was on closing British bases in Malaysia and Singapore, but it also mattered in the South Pacific where military roots were shallower. Nothing like the Five Power Defence Arrangements for Southeast Asia was contemplated for the South Pacific.

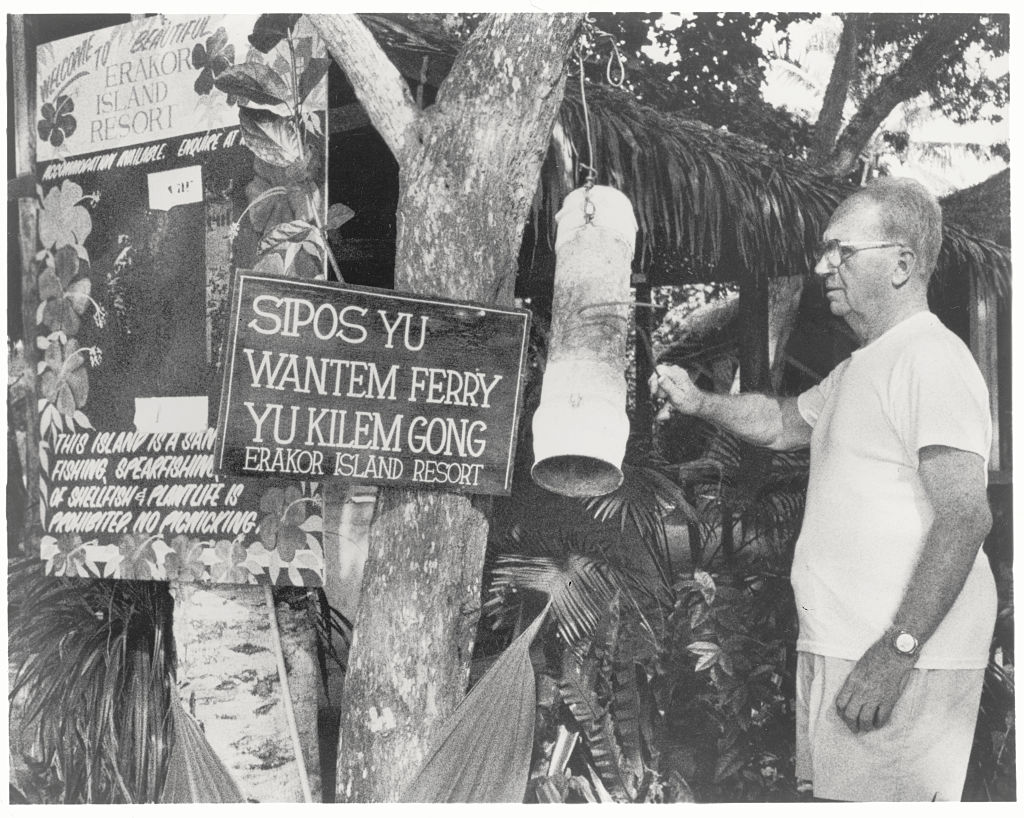

Australia and New Zealand would need to step up, and the newly-independent states of the South Pacific would have to define their own strategic future. A telling expression of this was the 12-week ‘Coconut war’ in the New Hebrides in 1980 as the French-British condominium became the nation of Vanuatu. France blocked British marines from taking any action against the mini-rebellion (the final spasm of the condominium as pandemonium) and Vanuatu had to call in troops from Papua New Guinea to put down the unrest.

The peace dividend for the peaceful islands is that only Papua New Guinea, Fiji and Tonga have their own military forces, while Vanuatu’s police have a para- military function. These small, lightly equipped forces traditionally look to Australia, New Zealand and France for equipment and training. The practical help expresses the security guarantee that Australia and New Zealand offer the English-speaking nations of Melanesia and Polynesia.

The new player seeking security partnerships in the islands is China, which was unsuccessful with its offer of a region-wide security treaty; now Beijing goes step-by-step with bilateral deals. China’s arrival confirms the history—expanding power systems reach the South Pacific.

Britain’s deepest continuing military ties are with Fiji, based on recruitment of Fijians. In 1961, the British Army struggled with volunteer recruitment after the abolition of national service. Recruiting teams were sent to three remaining colonies, and Fiji supplied 200 men and 12 women; about a third of the men served for 22 years or more.

Since 1998, Britain has regularly recruited soldiers from Fiji. Today, about 2200 Fijians are serving in the UK armed forces, most of them in the army. Fresh waves of Fijians keep volunteering. After the Covid lull, the tempo has lifted and in the last 12 months, Britain’s military has recruited 300 Fijians.

Britain’s ‘tilt’ to the Indo-Pacific was proclaimed by its 2021 integrated review of security and national policy. The review ‘made scant mention of the Pacific Islands within its broader tilt to the Indo-Pacific,’ judged the House of Commons foreign affairs committee. The refresh of the integrated review in 2023 gave more attention, promising to deepen ‘our engagement with Pacific Island countries and regional resilience’, and support ‘the Pacific Way’. Britain is a co-founding member of Partners in the Blue Pacific, to support the Pacific’s 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent.

Refreshing naval traditions, Britain has sent two Offshore Patrol Ships ‘to re-establish a permanent Royal Navy presence in the Indo-Pacific—the first time since the return of Hong Kong a quarter of a century ago’. Patrols have gone as far as New Zealand in the south and the Pitcairn Islands to the east. With no home port, the ships are a flexible asset at large in the Indo-Pacific. Smaller and more lightly armed than a frigate (with a crew of just 50), their size and capability matches well with South Pacific vessels; they complement rather than over-match.

Britain created a defence section at its Fiji embassy in February 2023, with coverage also of Tonga, Vanuatu and Solomon Islands. The British aim is not to enlist in a bidding war with China, but to act a good defence partner to the islands and complementary defence actor in the region.

Britain’s return to the South Pacific refreshes history as part of the tilt towards the new powerplay.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak says ‘China poses an epoch-defining challenge’ threatening ‘to create a world defined by danger, disorder and division’. The British tilt is a nod to Australia’s strategic declaration: ‘The Indo-Pacific is the most important geostrategic region in the world.’

In this century, the global balance will be set in the Indo-Pacific. As Britain wants a role in setting the Indo-Pacific balance, so it must resume a role in the South Pacific, as one element of the power system.

Britain helped create much of value in the South Pacific during the powerplays of the previous 250 years. The tilt to the islands has deep roots that mean Britain can seek to serve island needs as well as the Indo-Pacific balance. The twin purposes were equally emphasised by the House of Commons foreign affairs committee, pointing to both the ‘great strategic importance’ of the South Pacific and what Britain could do for island societies:

Support for Pacific Islands needs to be long-term and consistent to dispel the current perception that the UK is only responding to increased diplomatic activity in the region by other countries, especially China. While China has the resources to supply infrastructure to the Pacific Island countries, it may be a less helpful partner than the UK in developing free and open societies, and a high-risk provider of security and defence.

What Britain bequeathed to the South Pacific means its tilt to the islands comes loaded with much valuable history; that heritage means the South Pacific response has had no trace of ‘Not you again’.

Instead, the island message to Britain is ‘welcome back’.