Countering China’s coercive diplomacy

‘We treat our friends with fine wine, but for our enemies we have shotguns.’

— Gui Congyou (桂从友), former Chinese ambassador to Sweden, 2019

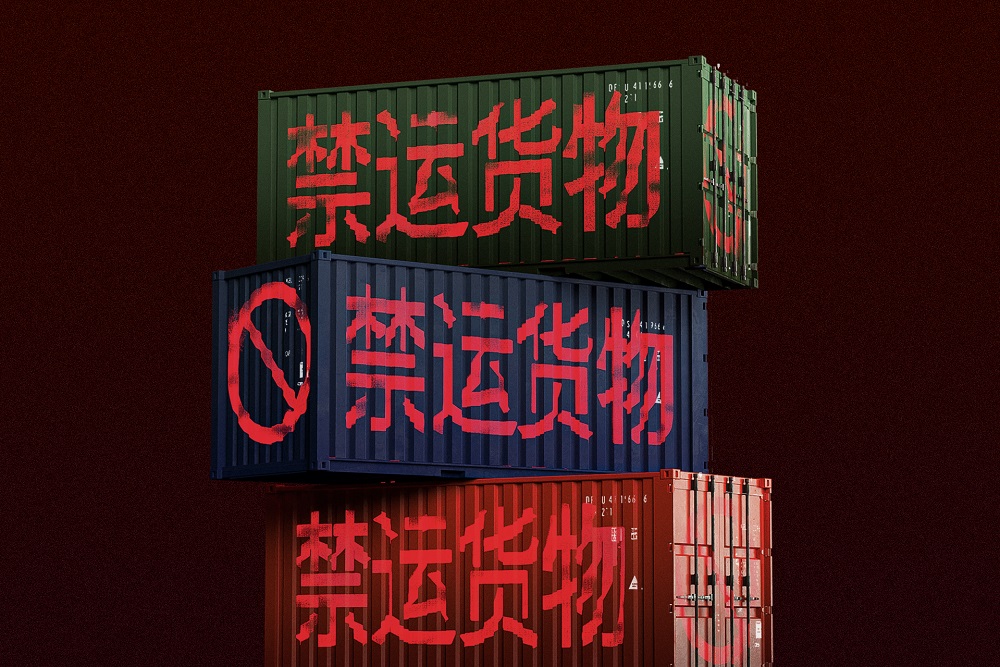

The People’s Republic of China is increasingly using a range of economic and non-economic tools to punish, influence and deter foreign governments. Coercive actions have become a key part of the PRC’s toolkit as it takes a more assertive position on its ‘core interests’ in its foreign relations and seeks to reshape the global order in its favour.

A new ASPI report, Countering China’s coercive diplomacy: prioritising economic security, sovereignty and the rules-based order, finds that the PRC’s use of such tactics is now sitting at levels well above those seen a decade ago. The year 2020 marked a peak, and the use of trade restrictions and threats from official state sources have proven the most favoured methods. Coercive tactics have been used in disputes over governments’ decisions on human rights, national security and diplomatic relations.

Over the past three years, the Chinese government has used coercive economic and non-economic tactics against at least 19 countries. The dominance of trade restrictions, followed by state-issued threats, reflects the PRC’s abuse of its global trading power and its exploitation of state-controlled media and ‘wolf-warrior diplomacy’.

Australia was the most targeted country as the PRC mounted a wide-ranging coercive campaign following a deterioration in bilateral relations, especially over Canberra’s call for an independent inquiry into the origins of Covid-19. Lithuania was the next most targeted, primarily because of the opening of a ‘Taiwanese representative office’ in Vilnius. In the dataset, Taiwan was the most common issue in disputes triggering coercive actions.

Advanced economic modelling, applied to this issue for the first time in a public research report, demonstrates how a flexible economy allows a state to be resilient and resist coercion. Markets adapt and sectors targeted by economic coercion can recover strongly as a result.

The PRC’s tactics have had mixed success in affecting the policies of target governments; most have stood firm, but some have acquiesced. Undeniably, the tactics are harming certain businesses, challenging sovereign decision-making and weakening economic security. The tactics undermine the rules-based international order and probably serve as a deterrent to governments, businesses and civil-society groups that have witnessed the PRC’s coercion of others and don’t want to become future targets. This can mean that decision-makers, fearing that punishment, are failing to protect key interests, to stand up for human rights or to align with other states on important regional and international issues.

Governments must pursue a deterrence strategy that seeks to change the PRC’s thinking on coercive tactics by reducing the perceived benefits and increasing the costs. The strategy should be based on policies that build deterrence in three forms: resilience, denial and punishment. This strategy should be pursued through national, minilateral and multilateral channels.

Building resilience is essential to counter coercion, but it isn’t a complete solution, so we must look at interventions that enhance deterrence by denial and punishment. States must engage in national efforts to build deterrence but, alone, it’s unlikely that they’ll prevail against more powerful aggressors, so working collectively with like-minded partners and in multilateral institutions is necessary. It’s essential that effective strategic communications accompany these efforts.

The report makes 24 policy recommendations. It recommends, for example, better cooperation between government and business and efforts to improve the World Trade Organization. The report argues that a crucial—and currently missing—component of the response is for a coalition of like-minded states to establish an international taskforce on countering coercion. The taskforce members should agree on the nature of the problem, commit to assisting each other, share information and map out potential countermeasures to deploy in response to coercion. Solidarity between like-minded partners is critical for states to overcome the power differential and divide-and-conquer tactics that the PRC exploits in disputes. Japan’s presidency of the G7 presents an important opportunity to advance this kind of cooperation in 2023.