‘Mum, I don’t want war’: heartbreaking messages from children under fire

Anyone unconscious of the impact of high-tech war on children should look at an exhibition of children’s art running now at the Australian National University.

They are drawings spanning seven decades, from survivors of Nazi horrors in World War II Poland, and children in Ukraine still being subjected to Russian artillery fire and missile attacks.

The exhibition, ‘Mom, I don’t want war!’ 1939–45 Poland/2022 Ukraine, is a Polish–Ukrainian archival project brought to Canberra by the Polish and Ukrainian embassies. It has been shown across Poland and in many other countries around the world. The Polish drawings were held in Warsaw’s Central Archives of Modern Records.

The drawings carry chilling messages, and they are all breathtakingly sad.

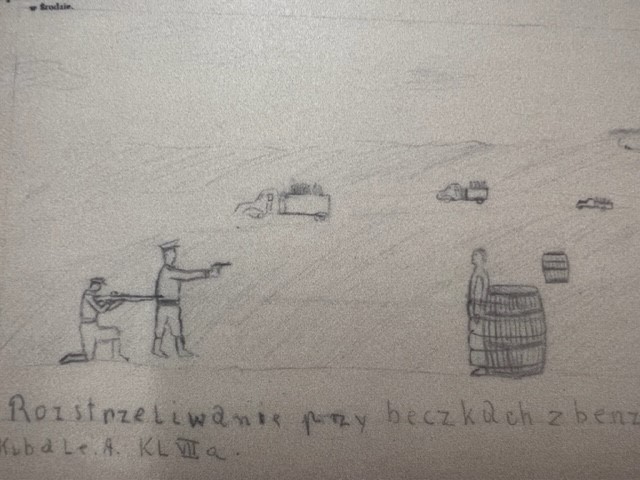

Some appear simple at first glance, until you register that the Nazi soldiers who’ve invaded Poland are about to shoot an unarmed man tied to a large barrel.

By A. Kubale, 7th Grade, Sroda, Poland.

Others have an awful sophistication. Outlined in a violent red, a child clasps a hand over a bloodied chest wound. There’s a teddy bear in a pool of blood on the floor nearby.

By Marho, aged 14 years, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Another, in stark black and white, shows a house with a fence and a girl huddled in a candlelit basement deep underground as a formation of helicopters thumps overhead and tanks blast across open ground nearby. There’s a coloured thought bubble as she remembers tossing a ball with a friend under blue skies and sunshine.

By Sofiia, aged 15 years, Korosten, Ukraine.

From Polish children of long ago are drawings of women and children fleeing ahead of tanks, of soldiers shooting men and women in a town square, and of people being rounded up by armed men.

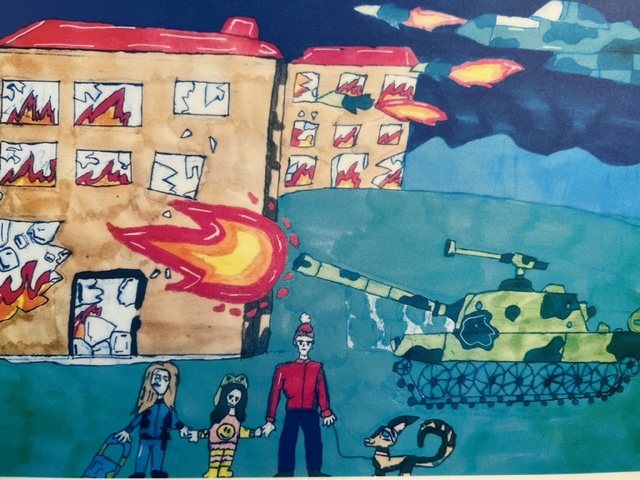

From Ukraine, there are fresher images from children of their families with mum, dad and the dog while a tank and an aircraft set the buildings around them ablaze, and of vivid explosions and apartment buildings with giant chunks bitten out of them by artillery shells and missiles.

By Mariia, aged 9 years, Kharkiv, Ukraine.

There’s a blank section in the exhibit for atrocities carried out by Russian occupiers in Poland. There are no such drawings because the Russians were in charge when the children were invited to sketch their impressions in 1946, a year after the war ended. Russian atrocities then were not included.

Welcoming guests, Katarzyna Kwapisz Williams, deputy director of the ANU’s Centre for European Studies, commented: ‘Normally when we look at children’s drawings, we smile a lot. Unfortunately, we will not be smiling much tonight.’

The inclusion of drawings from Polish children just after the end of World War II with those of children now suffering through Russia’s bombardment in Ukraine was particularly heart rending, she said. The images were strikingly, shockingly similar.

‘What seemed historical is still happening in the present day,’ Kwapisz Williams said. Seven million children were living the reality of a brutal war. ‘We have still not learned the reality that war is the worst thing.’

Ukraine’s ambassador to Australia, Vasyl Myroshnychenko, described how, at one point, he and his family were in Romania. He explained to his young son that they were safe there because Romania was a NATO member country, and the Russians would not attack.

When Myroshnychenko brought his family to Canberra, the boy asked him if Australia, too, was a NATO country, or ‘will Russia attack us here?’