Australia must do more to secure the cables that connect the Indo-Pacific

In January, the UK’s defence chief, Tony Radakin, warned that Russian submarine and underwater activities were directly threatening subsea cable systems. There’s speculation that Russia could cut cables if it further escalates the war in Ukraine.

In July, the former head of Mauritius Telecom accused the country’s prime minister of having bypassed processes to grant access to a ‘technical team’ from India to install a device that would monitor internet traffic at the landing station of the South Africa Far East submarine cable at Baie Jacotet in Mauritius.

Closer to home, the president of the Federated States of Micronesia, David Panuelo, wrote to his fellow Pacific island leaders in May about the regional risks of the China – Solomon Islands security agreement, pointing out that the ‘bulk of Chinese research activity in FSM has followed our nation’s fibre optic cable infrastructure’.

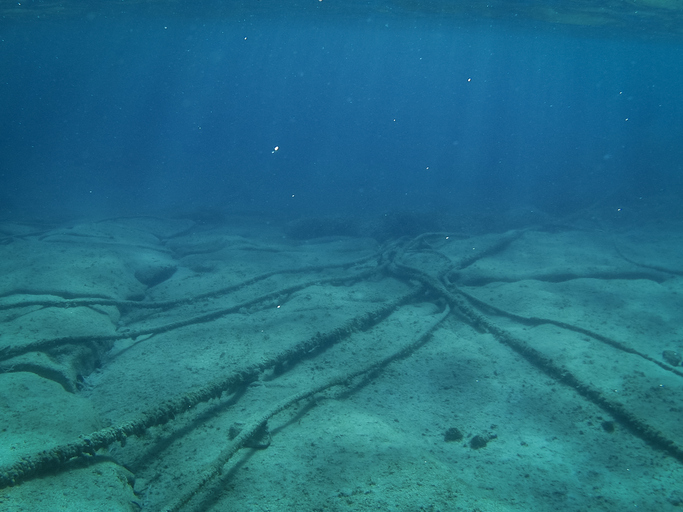

In a recent paper, we argue that a comprehensive approach is required to address the resilience of undersea communications cables. There are more than 430 subsea cables that may be targets for anyone wishing to disrupt global connectivity. These cables transfer more than 95% of international communications and data globally. They are core critical infrastructure and underpin the internet, financial markets and digital economies.

All it takes to damage a cable is a merchant ship or fishing boat dropping its anchor on a cable not far from the coast. In January, an underwater volcano shattered Tonga’s internet infrastructure—a single cable connecting the archipelago to the global internet. It took five weeks to fix. Fishing and anchoring incidents account for approximately 70% of cable faults globally. Divers, submersibles or military grade drones could place explosives on the cables or install mines nearby, which could then be detonated remotely. Cable repair ships could be attacked.

Several nations in the Indo-Pacific operate submarines capable of stealthily tampering with cables, although it’s technically challenging to do and there are easier ways to obtain data. But cable-laying companies can potentially insert backdoors or install surveillance equipment. By hacking into network-management systems, attackers could control multiple cable-management systems. Terrorists and criminal organisations could exploit cable vulnerabilities for different purposes.

But the bigger threat is cable interference at data points or landing stations. Sydney and Perth are the primary points where cables land in Australia. Power could be cut to those sites or explosive devices detonated. Missile attacks are possible. Landing station locations are vulnerable because data can be intercepted and ‘mirrored’ (that is, copied while the sender and receiver are none the wiser).

While US, French and Japanese corporations have dominated the subsea cable market for many years, Chinese firm HMN Tech (formerly Huawei Marine Networks) now has a global market share of about 10%. Recognising China’s hunger for data, in 2021 the World Bank–sponsored East Micronesia Cable tender was cancelled for fears HMN Tech would win. Last year a consortium of companies including Google and Facebook ditched the Hong Kong conduit of the Pacific Light Cable Network due to data integrity concerns. It was to be a super-fast direct fibre-optic link between the US east coast and Hong Kong.

When it comes to the Pacific, Australia and its partners should continue to fund and co-fund cable projects to fend off Chinese-backed alternatives. This includes monitoring HMN Tech proposals and tenders and seeking to encourage and facilitate alternative suppliers where possible. In May, a draft maritime cooperation agreement between China and Solomon Islands was leaked. China’s goal, it stated, is to develop ‘a maritime community with a shared future’ by building wharves, shipyards and submarine cables for Solomon Islands.

Australia is already a part owner of the Coral Sea Cable Company, which connects Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands to Australia. The Australian government also partnered in 2020 with Japan and the US to finance an undersea cable to Palau. More can be done together with these partners, as well as India, the UK and the EU, to fund and back new cables in the Pacific.

There’s no international treaty to protect against physical or cyberattacks on undersea cables, but at a national level Australia’s submarine cable protection regime is considered a regional gold standard. Australia’s Telecommunications Act 1997 declares ‘protection zones’ around cable routes, restricts potentially damaging activity, criminalises cable interference and requires permits to lay new cables. While each country’s geographic circumstances are different, promoting the adoption of similar legislation by Pacific island nations would better safeguard their vulnerable cables from accidental damage and breaks.

Australia can work with its Pacific partners to facilitate greater information sharing on threats to the undersea communications network and strengthen limited regional cable-repair capabilities. We should work with regional maritime agencies to integrate cable surveillance into national and regional maritime domain awareness systems and establish national registers for government and industry points of emergency contact on cable resilience. Should China ink more security deals with Pacific island nations, the battle to lay, operate and repair this critical infrastructure will intensify. We should prioritise cable diplomacy in the Pacific to safeguard this essential international public good.

The Australian government should also back the commitment made by the Northern Territory government to connect Australia to the trans-Pacific cable. Last year’s AUSMIN communiqué noted that both sides ‘welcomed the Northern Territory government’s commitment to connecting Australia to the trans-Pacific cable, which will enhance digital connectivity between Australia and the United States and support critical infrastructure in the Indo-Pacific’.

The mooted branch line to Darwin would cost around $100 million. It would be the only undersea cable connecting the US to Singapore with a national-security-rated capability that doesn’t transit the South China Sea. It’s a secure, low-latency, high-speed data link to the US and Asia. Building a connecting branch to Darwin would be a vital enabler for the Australian Defence Force, for national security more broadly and for digital access to Southeast Asia’s fast-growing market of 680 million people.

Despite the boom in undersea communications cables, Antarctica is the sole remaining continent without fibre-optic communications connectivity. But there’s now bold talk by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology of running a subsea data cable connecting the Mawson, Davis and Casey stations on the Antarctic continent, and the Macquarie Island research station, to Tasmania. Such a connection would pose challenges, mainly in the form of icebergs. But if it went ahead, it would provide unprecedented speed of communications and reliability and strengthen Australia’s position in our geopolitically contested southern flank.

And in the near future it won’t just be undersea communications cables and infrastructure that will require protection. As we push ahead on clean energy, we’ll see more undersea transnational electricity cable connections to solar farms and offshore wind farms, with significant environmental and energy security benefits. Infrastructure Australia recently provided its endorsement for the economic benefits of the Australia–Asia PowerLink project. Commencing in 2024, it would export solar power from the Northern Territory to Singapore via a 4,200-kilometre submarine cable from Darwin and provide up to 15% of Singapore’s power supply. The Indonesian government has already approved the cable route and granted a permit to conduct subsea surveys in Indonesian waters to map the underwater route to Singapore.