Myanmar executions expose regime’s desperation

The execution of four political activists by Myanmar’s military junta reveals the regime’s desperation. Myanmar has endured decades of military rule and brutal oppression, but these were the first death sentences carried out in 34 years. They were announced on 25 July in a brief report on the bottom of page 2 of the Ministry of Information–controlled newspaper, The Global New Light of Myanmar.

The killings represent a new low point in Myanmar’s human rights record and raise the question, why now?

On 1 February 2021, Myanmar’s military commander-in-chief, Min Aung Hlaing, mounted a coup detaining President Win Myint, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and numerous other National League for Democracy (NLD) politicians who were scheduled to convene that day to elect a new president. A state of emergency was declared and the right to exercise legislative, executive and judicial powers was transferred to the commander-in-chief.

Opposition to the coup was spontaneous and evident throughout the country and involved all age groups. International condemnation was swift. North American and European countries imposed sanctions on senior military personnel and military-owned businesses.

Min Aung Hlaing miscalculated the nation’s mood. The people had made it clear at the ballot box they wanted to be governed by Aung San Su Kyi’s NLD and not by a military-affiliated political organisation such as the Union Solidarity and Development Party. The peaceful protests, initially tolerated, didn’t subside and the military commenced a bloody crackdown. The people of Myanmar, addicted to their new limited form of democracy and enhanced freedoms, weren’t prepared to return to the dark days of incompetent military rule.

Local militias called People’s Defence Forces were formed and engaged in urban guerrilla warfare using explosives and targeted assassinations in response to the disproportionate use of force by the military. The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners says more than 2,100 people have been killed by security forces since the coup. Four more names have now been added to that toll.

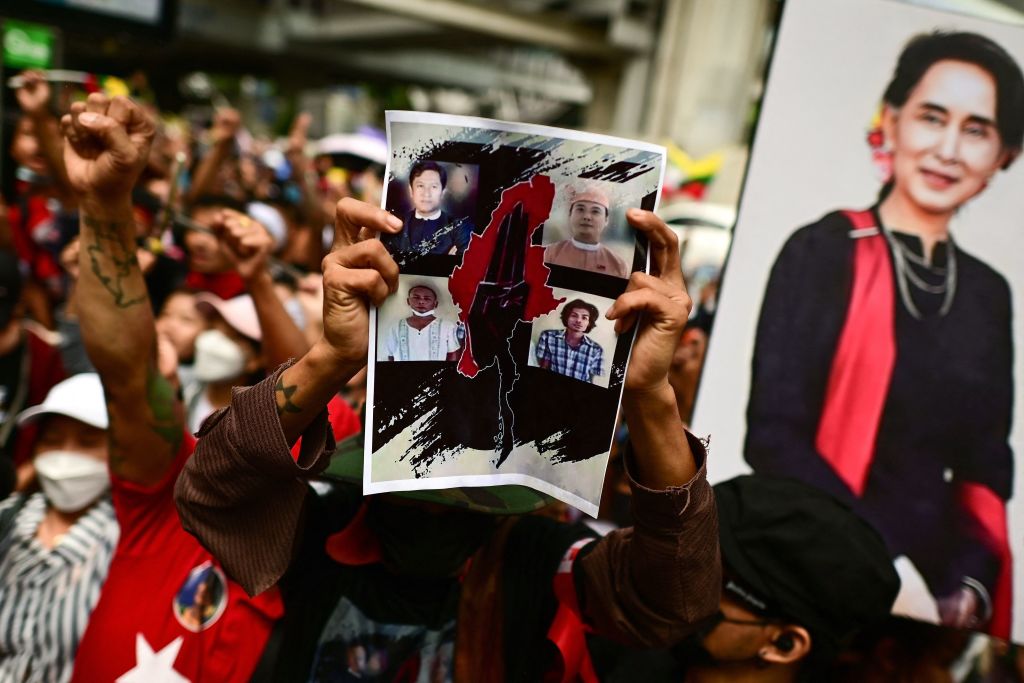

The four men were charged with helping militias fight the army and were sentenced to death in closed-door trials. They included Kyaw Min Yu (better known as Ko Jimmy), a veteran of the so-called 88 Generation that led the student uprising in 1988, and Phyo Zeya Thaw, a celebrated hip-hop singer, former member of parliament and ally of Aung San Suu Kyi. Two other lesser-known activists—Hla Myo Aung and Aung Thura Zaw—were sentenced to death over the killing of a woman who was allegedly an informer for the junta.

The killings have sent a chill throughout Myanmar and dampened hopes for a return to civilian rule.

Min Aung Hlaing abused Myanmar’s constitution by incorrectly claiming that the elections were not free and fair, that this amounted to a wrongful and forcible means of taking power, and that it was thus the military’s duty to declare a state of emergency. In another vain attempt at legitimation, he has announced that fresh elections will be held in mid-2023. If elections are held, and we can never assume the commander will keep his word, they are likely to be boycotted by the NLD and will be held in an atmosphere of fear. That’s his cynical reason for carrying out the death penalty now. Brute force has failed to break the spirit of the people and the commander is desperate for a victory. His generals and the cronies’ business interests are hurting, and they won’t be acquiescent forever.

The elections are also likely to be held under a changed voting system favouring a military-aligned party. The outlook, then, is for a continuation of military rule either directly or through a proxy political party.

Here the commander miscalculates again in thinking the people will accept reversion to the decades of military rule. The Myanmar of today is very different from the Myanmar of a decade ago. A digital transformation has opened society to the world beyond hard borders. They have tasted freedoms, they have seen protests in other countries, and they know tyranny can be overthrown through people power.

And they have had enough. The People’s Defence Forces have formed links with ethnic armed groups for training and access to safe havens. Increasingly, calls are being made for international assistance to move beyond the humanitarian and to include military equipment. If for Ukraine, they ask, why not for Myanmar? So far, there’s no sign of military assistance being provided to the militias, but the calls for it indicate that the pro-democracy movement remains opposed to a negotiated settlement, as does the military, and no end to the conflict is in sight.

The international community has strongly supported ASEAN efforts to help Myanmar find a peaceful solution that returns the country to democracy. This support and the ASEAN efforts have been criticised for their apparent acceptance of Min Aung Hlaing’s commitment to ASEAN’s five-point consensus, which calls for an immediate end to violence, constructive dialogue and humanitarian assistance. Well over a year after the commander and all ASEAN leaders agreed on the five points, there’s been no sign of implementation. ASEAN has responded to this betrayal by inviting only non-political representatives from Myanmar to its meetings, effectively snubbing the military leadership.

Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen, the current ASEAN chair, appealed to Min Aung Hlaing to reconsider the death sentences. Totally ignored, ASEAN has issued a statement denouncing the executions as ‘highly reprehensible’ and warning that they set back advancing the five-point consensus. This is indeed strong language from an organisation famous for its non-interference in the internal affairs of member states.

All the international community’s statements of concern and condemnation and ASEAN efforts have failed to end the violence or reverse the coup. European and North American sanctions and non-government organisations’ advocacy have similarly failed. Myanmar’s military has again shown that it’s impervious to international pressure and opprobrium. It will bunker down and resist both the people’s wishes and foreign pressure.

This does not mean the world should sit on its hands and watch Myanmar descend further into chaos. Statements and sanctions serve purposes other than regime change. They are a statement of a nation’s values, they express the international community’s expectations of acceptable conduct by governments, and they are a message of solidarity with the people of Myanmar.

The harsh reality is that change will only come from within Myanmar and, given the strength of the military relative to its opposition, only from within the military itself. This is all the more reason to increase pressure on Myanmar’s military leadership.