Will the Quad deliver on its promises?

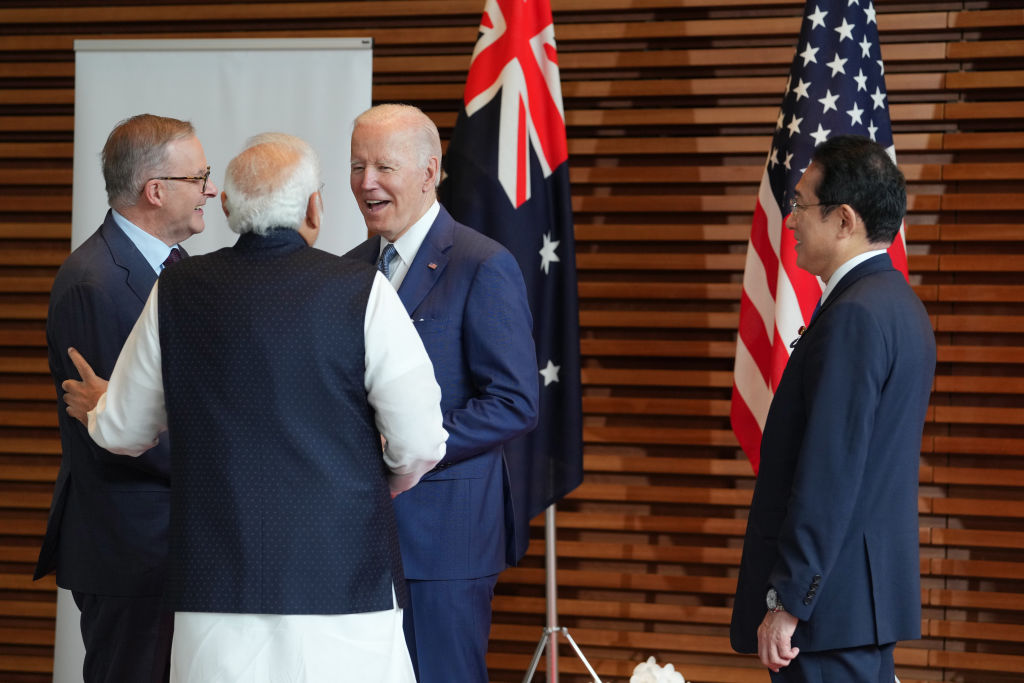

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue met in Tokyo late last month to affirm the continued cooperation between the United States, Australia, Japan and India to promote regional stability in the Indo-Pacific. But the leaders left the meeting offering a divided response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, raising questions about the Quad’s ability realistically to serve as a democratic deterrence against unilateral change to the status quo by force.

While the Quad members have agreed to promote a free, open and rules-based order, they have mostly turned towards existing functional cooperation rather than forging new commitments that could deepen their role in promoting regional stability. The Quad is not a treaty-based alliance and doesn’t have any concrete commitment to collective security in the Indo-Pacific region. AUKUS has also been cast as part of a broader regional plan to counter Chinese influence in the maritime domain that somehow discharges Quad members from coordinating against China.

The Quad remains a consultative group rather than an operational body, especially in the security domain. Quad countries have aligned existing interests to provide public goods during the Covid-19 pandemic, engage peacetime competition to reorganise regional supply chains, build infrastructure and secure technological development. The summit in Tokyo took a further step into contested waters in the Indo-Pacific and cybersecurity, leading to a partnership over maritime security and data sharing. These efforts not only aim to invest in the strength of the United States and its allies but also build a foundation for a more resilient rules-based order.

But its limitations should be recognised in order to achieve its objectives. The Quad failed to collectively criticise Russian aggression in Ukraine as violating the principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity and directly threatening the foundation of international peace and security. This recent failure to reach an agreement shows that resolve among the four countries’ shared vision of promoting a rules-based order can be compromised at a crucial moment.

The Quad has also been hesitant to include other countries into its security architecture. The goal of promoting a free, open and rules-based order is only possible when the Quad becomes more inclusive by expanding its architecture to provide greater legitimacy to the Quad’s Indo-Pacific vision. The existence of minilateral and multilateral cooperation beyond the Quad demonstrates differing willingness and capabilities in its members’ contributions to achieving the Quad’s collective vision.

The Quad should develop a long-term strategy for deterring a revisionist China, including encouraging more like-minded countries to support a rules-based order in the region and to complement the hub-and-spokes alliance system. The inclusive nature of the regional security architecture will decrease the chance for China to divide allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific. Inclusiveness will allow Quad members to find more diverse areas of cooperation vulnerable to coercion and to pool relevant capabilities for sustaining the rules-based order. Current global challenges cannot be shouldered by the Quad alone.

The United States must also engage the region more assertively. Revitalising the Quad has reassured allies in the region, but there are concerns about the lingering effects of ‘America first’. For example, the Biden administration’s lack of will to return to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership has been challenging for Australia and Japan.

The US strategy towards China is framed as ‘invest, align and compete’, and prioritises strengthening the US economic and technological leadership and rebuilding US dominance. While the Biden administration recently launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity to help achieve these goals, regional countries are likely to join other trade agreements to hedge the risk from fluctuating global supply-chain crises amid the war in Ukraine and China’s zero-Covid policy.

In the meantime, China is also expanding its own minilaterals through the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement with Chile, New Zealand and Singapore which excludes the United States.

While the Quad has waded through a series of global crises, its status and domain of cooperation are still developing. It is hoped that the four countries might focus on the initial goal of reinvigorating the Quad amid great-power competition, especially in promoting the rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific. Members need to be equipped with a more operational edge, and a willingness to build an inclusive architecture, supported by greater US assertiveness in the process.