Quad leaders’ summit highlights Australia’s and Japan’s opportunities for regional leadership

The relative decline of US influence in the Indo-Pacific has upset the regional status quo and leaves a clear power vacuum. With little sign of the US presence being quickly restored to what it once was, there is a pressing need for Australia and Japan to assert themselves as regional powers.

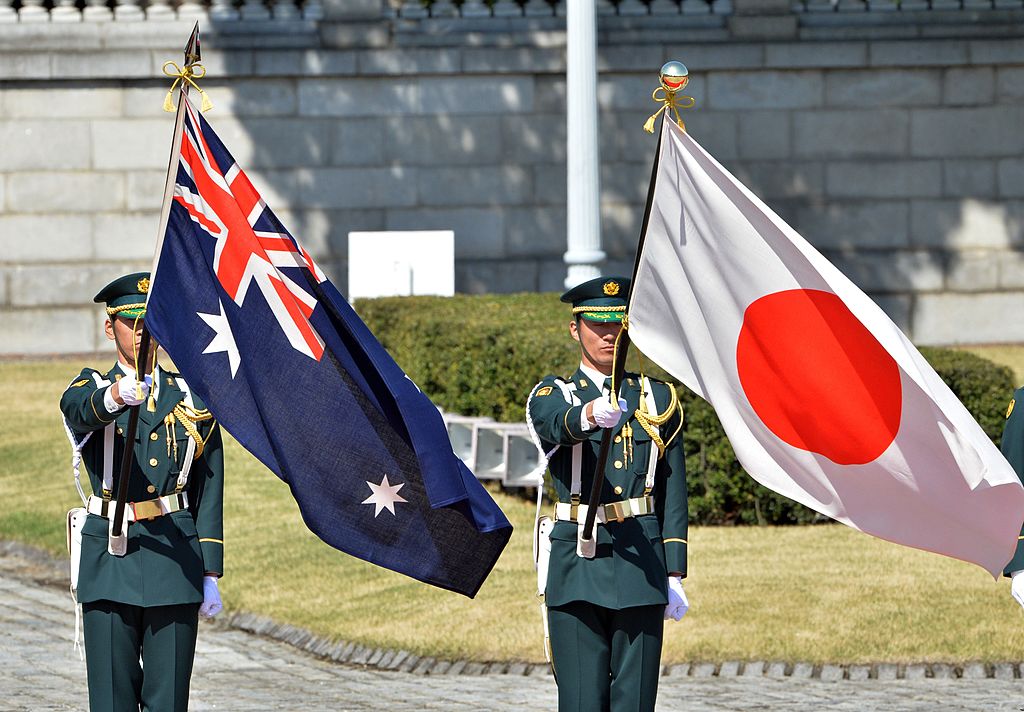

Australia and Japan have been two of the most active advocates promoting the Indo-Pacific as a uniting concept for regional cooperation and recent threats to their shared security interests have seen enhanced momentum towards deepener security cooperation. The recently signed landmark reciprocal access agreement takes bilateral defence and security cooperation to an advanced level, however, more must be done to truly meet today’s challenging security dynamics.

US President Joe Biden flew to Japan to meet Prime Minister Fumio Kishida before today’s Quad leaders’ meeting in Tokyo. It’s Biden’s first visit to Japan as president after more than 12 months in office and is an important attention counter-point to the war in Ukraine. Both the Biden–Kishida and Quad summits provide opportunities for Japan and Australia to remind the US of its critical role as a regional stabiliser and to workshop complementary regional approaches. That reminder can’t come soon enough.

Indo-Pacific regional dynamics have evolved dramatically in recent years. The US is more stretched and distracted, China’s approach is increasingly coercive, non-traditional security issues affect the region and now Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has uprooted decades of European stability. As these challenges become increasingly pressing, Australia and Japan need to develop a collective balance of power to uphold a free and open Indo-Pacific. Key to doing this will be engaging with the US in new and meaningful ways as it seeks to redefine its regional presence.

The future of US engagement in the region will look different to what we have seen previously. Under its new strategy of ‘integrated deterrence’, the US will not rely on its strength alone but implement a framework for operating with allies in both conventional and non-conventional areas of conflict. This will be a long-term effort requiring shared political will, capabilities and interoperability among countries: an agenda both Australia and Japan support and other US partners should embrace.

As regional leaders, Australia and Japan can utilise their established relationships with ASEAN, South Korea and European countries to help the US redefine its role in the Indo-Pacific against a backdrop of collective deterrence. With more regional countries involved, China’s decision-making will be more complicated and smaller countries could feel empowered to push back against Beijing’s coercive practices.

With greatly reduced strategic warning time, integrated deterrence—facilitated by capability-sharing agreements, will be key to meeting growing threats to regional stability. This preparation can be bolstered by more access agreements, joint exercises, capability development and information sharing. The reciprocal access agreement is a step in the right direction and both Australia and Japan should continue to extend their defence agreements to other like-minded regional partners to contribute towards this end. By shifting towards integrated deterrence, Australia and Japan can open discussions with the US on how the three countries can work together with partners in new ways and provide greater regional leadership.

Australia’s strategic mindset has shifted in recent years to one that is complementary with integrated deterrence. While historically Australia has engaged with the region through a bilateral perspective, more recently it has prioritised multilateral groupings like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, the Quad and AUKUS. In future, Australia’s influence will be measured by what it offers multilaterally, rather than bilaterally. Adopting an approach of integrated deterrence will be an effective means to this end.

Meanwhile, Japan has outwardly expressed its intent to accelerate integrated deterrence with the US. Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party commenced a review of Japan’s national security strategy in late 2021 and at the recent virtual US–Japan security consultative committee meeting Japan’s foreign and defence ministers committed to aligning Japan’s strategic defence documents with those of the US. As integrated deterrence appears increasingly necessary, Japan has also increased its defence spending and discussion around amending Article 9 of the country’s constitution is gaining traction.

While Australia and Japan have a special strategic partnership, it is not a combined strategy to respond specifically to US decline. The next step for these two countries is to formalise their thinking to articulate a common Indo-Pacific strategy—one that includes the US doctrine of integrated deterrence and builds regional networks towards a collective balance of power. As Quad countries come away from the leaders’ meeting in Tokyo, the success of the summit will be measured by demonstrated movement towards a more comprehensive security agenda.