Hamartia, tragic righteousness and America’s ‘forever wars’

Aristotle defined tragedy as the story of the inexorable downfall of a hero, not from greed or vice, but from human error or frailty. Harmartia is that tragic flaw. Two thousand years ago, the Greeks wrote plays to show that the innate trait that doomed the protagonist might be an admirable one.

Is righteousness America’s hamartia?

On an evening years ago, I was doing paperwork at my desk, the commanding officer of an Australian Army Reserve unit. One of my captains told me: ‘Sir, another plane has hit.’ I watched the TV as drama became disaster, and I watched my officers, curious about what this might reveal of them. I wondered what it might portend for us all. My memories are not only of the soul-chilling horror of it all, but also of a disorientation that prompted momentary schadenfreude and unmediated questioning.

The words of one young officer remain clear: ‘The Americans will never fall for this.’

Was 9/11 a provocation?

In 1975, David Fromkin explained terrorism as psychological jujitsu, the uncertain and indirect strategy of inducing response. ‘First the adversary was made to be afraid, and then, predictably, he would react to his fear by increasing the bulk of his strength, and then the sheer weight of that bulk would drag him down.’

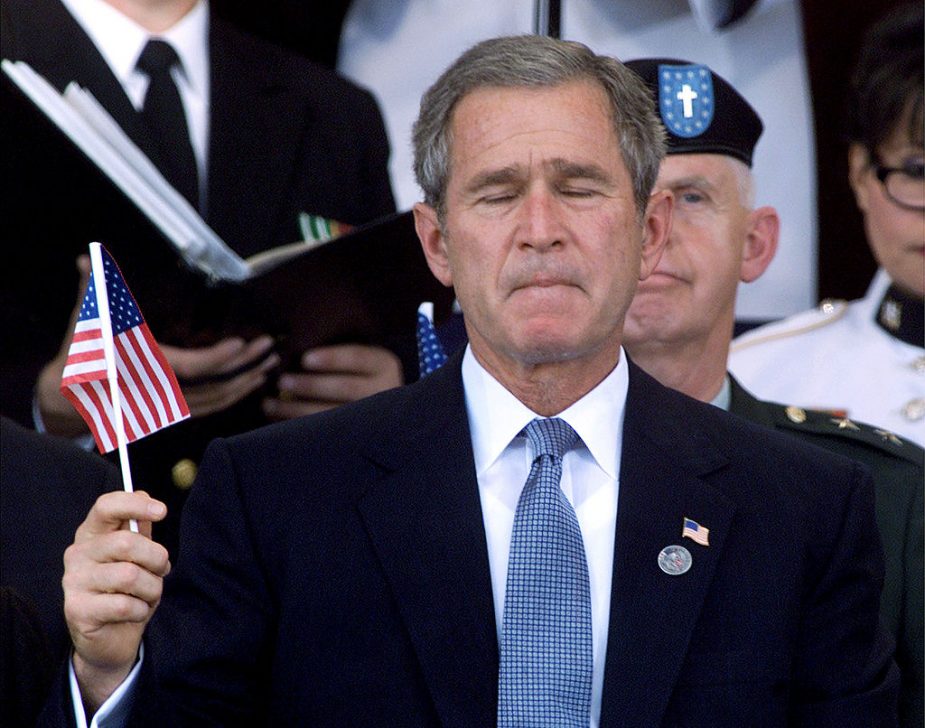

In the days after the aircraft struck, wise voices warned clearly and presciently. On 20 September 2001 they were silenced. There could be no reflection on motive in the face of the binary sentiment unleashed by President George W. Bush’s stark logic: ‘Either you are with us or you are with the terrorists.’

Did Osama bin Laden intend to lead the US on a path of failed counterinsurgencies, loss of moral and strategic standing, and the invigoration of Salafism? Researchers analysing bin Laden’s papers deny such planning. It doesn’t matter. What mattered was the response. Fromkin’s essential insight was that terrorism wins ‘only if you respond to it in the way that terrorists want you to’.

It seems that America did respond in a way that served al-Qaeda objectives. With hindsight, many now condemn the political leaders of that time, forgetting perhaps that having framed the attacks as war, not crime, those leaders and their successors were then borne along on an irresistible tide of public desire for vengeance. A sentiment that, in the words of David Kilcullen, was and long remained ‘beyond bounded rationality’.

We are now wading through a media high tide of retrospective analysis. Where’s the exploration of how horror and shock turned ‘ordinary folks’ into avenging angels?

In 2000, I had come to know some Americans from the petroleum industry, mostly Texans, who had visited Australia. We cheerfully exchanged news and jokes in emails. I considered them friends. After 9/11, the nature of their communications changed dramatically and took what I feared was a sinister direction. These included photos of sailors on an aircraft carrier writing crude messages on bombs to be dropped on Afghanistan. It also included a map of that country coloured blue and labelled ‘Lake America’.

I emailed these Americans saying that I believed a true friend stands by in time of need, that Australians were with the US and Britain in this, and that I also believed that a true friend must be ready to say what is unpalatable. I said that much of the comment from the US carried the theme that it was somehow amusing to bomb Afghanistan. I have no problem with black humour; it’s a healthy way to deal with distress. But this stream of images and ideas had become vengeful glee and that filled me with sadness.

I urged them to please think about why people were prepared to give their lives to strike at the West and said that if we did not figure out the causes and address them, we and our children were doomed to spend our lives in a cycle of violence, never able to travel the world safely.

What I wrote was framed carefully. I said: ‘I am no apologist for our enemies or for terrorist methods. I am a soldier. I have attended too many of my friends’ funerals (ironically killed by IRA terrorists funded heavily from New York). There is a need to act, but we should act with regret and reluctance, knowing that we too are killing innocents and recognising that by accepting “collateral damage” we have given up much of our claim to moral superiority. We should not demonise our enemies either, even the psychologically warped young extremists of the Taliban, because that will blind us to the understanding we must have for our cause to prevail.’

The responses I received shook me to the core. One said: ‘Do not ever send me another e-mail.’ The message, clearly written in haste, went on to say that it was easy for us in Australia to sit in the middle of nowhere and feel superior and do nothing, and then to complain to those who did act. ‘This puts you right in there with Canada and France as blood suckers of the world,’ the writer said.

That left me shocked and saddened. These were educated, well-travelled people—good people. My questions ultimately took me on a path to a PhD examining counterproductive political overreactions. Yet, my overriding impression from the responses to my email then, and now, was of a violent Salafist ‘gotcha’.

An American scholar related that merely proposing the hypothetical retrospective question of ‘doing nothing’ to a conference of terrorism academics saw him physically threatened. He and others have observed how 9/11 didn’t merely suspend critical thinking, but rather prohibited it.

This illustrates the innate genius of the attack. Do something so terrible that it lights a fire of righteousness within your enemies. Set a fire in what is best in God-fearing America, the grim determination to see a morally necessary task through—that which saw sacrifice for Europe in 1917 and 1942. Trigger what John F. Kennedy espoused of the US: ‘we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship’.

Hamartia. The first act of the tragedy seems reasoned, and attacking Afghanistan is blessed with initial success. Then unbounded rationality does its work, and the 20-year tragedy unfolds.