ASPI’s decades: Urgently eating the defence elephant

ASPI celebrates its 20th anniversary this year. This series looks at ASPI’s work since its creation in August 2001.

‘It’s a very encouraging sign that industry can meet the challenge of ‘eating the elephant’ presented by the 2020 Defence Strategic Update’s growing acquisition program.’

— Marcus Hellyer, The cost of defence: ASPI defence budget brief 2020–2021, May 2021

Australian industry is showing the appetite for ‘eating the elephant’, the big task of producing new defence equipment.

A lot more of the defence elephant is going on to the plates of Australian companies.

Not so long ago, industry policy was damned as hampering the need to get the best possible kit. Now Australian industry gets to pour the gravy on the elephant.

In the new era of ‘sovereign industrial capability’, the local makers are lordly as they’re embraced royally. The Covid-19 era confirms (and clinches) the concept.

Defence’s spending on locally made military kit is growing in absolute terms and in relative terms compared with purchases from overseas. That dimension of the government’s defence industry policy is delivering.

Taking over as ASPI’s senior analyst for defence economics in 2018, Marcus Hellyer remarked that it was amazing how a few years could change the industry environment:

The Abbott Coalition government came to power [in 2013] with a defence industry policy that was essentially indistinguishable from its broader industry policy. Subsidies were a bad thing, and just as the government wasn’t going to subsidise Australian industry to build cars, so it wasn’t going to pay extra to build military equipment in Australia. Defence’s investment plan was first and foremost about military capability, not nation building or supporting local industry.

Times (and prime ministers) have certainly changed, and changed quickly.

To let anyone track the cash, Hellyer set up a Cost of Defence public database, making available much of the data on the defence budget and spending that ASPI had accumulated since it was established in 2001. The categories of data available for download are defence funding, the capital program, the sustainment program, personnel, flying hours and costs, the cost of operations, the defence cooperation program, shipbuilding and external data sources.

Amid the tough times and bad economic news of Covid-19 in 2020, Hellyer judged the 2020 defence strategic update (DSU) ‘a remarkable commitment by the Australian Government to sustained growth in the defence budget’.

Confirming the robust funding line of the 2016 defence white paper, the defence budget would continue to grow past 2% of GDP, ‘and indeed at a faster rate than before the Covid-19 pandemic hit’. The government had declared that Australia’s strategic circumstances had deteriorated significantly: ‘It states that the region is in the middle of the most consequential strategic realignment since World War II. That brings significant uncertainty and risk. The government regards robust military capabilities as essential to managing it.’

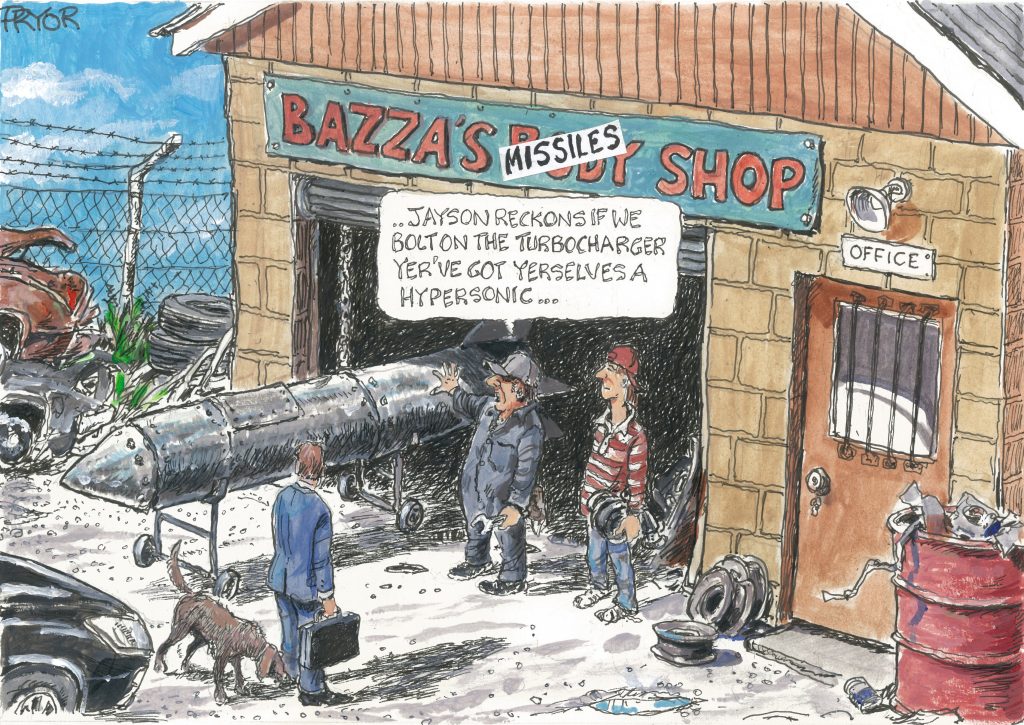

The DSU stated that a largely defensive force won’t deter attack, Hellyer noted. Instead, ‘new capabilities are needed to hold adversaries’ forces and infrastructure at risk from a greater distance. They include longer range strike weapons, cyber measures and area denial systems.’

Among the risks, Hellyer wrote, much of the planned force was still a long way off in the future. And Australia was confronting the industry policy trap of preferring industrial outcomes to military capability. Some of the hidden costs of continuous build programs were becoming more apparent. A key question, Hellyer concluded, was whether Defence could internalise the urgency, and change the way it did business:

We now have a plan that calls for speed, lateral thinking, innovation and partnerships—to be implemented by an organisation that’s slow, subject to groupthink, risk averse and reluctant to reach out. Adapting Defence to the demands of our new reality is going to be challenging, to say the least.

In the 2021 budget, consolidated funding (including both the Department of Defence and the Australian Signals Directorate) was $44.6 billion, which represented real growth of 4.1%. Hellyer noted that it was the ninth straight year of real growth, and, according to the DSU funding model, that would continue until the end of the decade.

In 2020, defence cash hit 2.04% of GDP, meeting the government’s promise to restore the defence budget to 2% of GDP by 2020–21. In 2021, it was projected to reach 2.09%. Both the 2.04% and 2.09% numbers were ‘smaller than predicted a year ago, as GDP has recovered faster than expected. It’s a salutary lesson on why we shouldn’t obsess too much about small changes in percentages of GDP.’

Spending on military equipment, facilities, and information and communications technology had all set records, Hellyer said: ‘That’s quite an achievement in the middle of a pandemic.’

Drawing together issues of cash, kit and capability with the ticking strategic clock, Hellyer saw a ‘fundamental disconnect’ between strategic assessments and the capabilities of the force structure being planned and built:

The DSU emphasised the need for long-range strike capabilities that can impose cost on and deter a great-power adversary at distance. Yet the ADF’s strike cupboard is bare, and there’s no clear path to restock it quickly. Moreover, huge investment is planned in capabilities that appear to have minimal deterrent effect on a great-power adversary, such as up to $40 billion on heavy armoured vehicles.

Overall, the force structure and timelines for delivery are holdovers from previous strategic planning documents developed in circumstances that bear little resemblance to our current one.

Fundamental changes to concepts and force structure, such as making greater use of uncrewed and autonomous systems, are occurring only slowly.

The vast bulk of investment is still going into small numbers of exquisitely capable yet extremely expensive crewed platforms that take years, even decades, to design and manufacture and are potentially too valuable to lose. Defence needs to take more risk and invest more than half of one percent of its budget in R&D, particularly in distributed, autonomous technologies.

The government has delivered the steadily increasing funding it promised at the start of 2016. That was commendable, considering the economic impact of Covid-19. Yet, while Australia’s strategic circumstances had deteriorated since 2016, Defence’s funding model hadn’t changed, Hellyer concluded:

More funding is needed, but Defence will need to show that it can use it well to deliver capability rapidly. Over the decade, the government is providing $575 billion in funding to Defence, but in that time it won’t deliver a single new combat vessel.

Defence will need a ‘sense of urgency’ in confronting the complexities of kit, cash and capability.