Where does the withdrawal of US and allied forces leave Afghanistan?

As the US and allied military exit gathers pace, war-torn and Covid-19 ravaged Afghanistan faces a multifaceted transition. The country is once again positioned to embrace a political, economic and security transformation of a magnitude that could seriously impact its survival as a defendable functioning state. The US and its allies have promised to continue their non-combat support, including funding the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF). But this can’t be taken for granted. Afghanistan stands to experience more violent, murky and uncertain times ahead. The direction the country will take after 11 September 2021 will depend on whether its conflict is resolved on the battlefield or through a negotiated settlement.

Afghanistan could follow one of three directions. The first is that it stays on its current course of conflict for some time, with a chaotic and divided system of governance remaining in place in Kabul. This would be contingent on two important imperatives: that the ANDSF remains coherent and effective, and that the US fulfils its promise to meet US$3.3 billion out of the ANDSF’s US$4-plus billion in annual funding and backs with air power the ANDSF’s defensive operations whenever Kabul or another major city is at risk of falling to the Taliban. Even so, as suggested by American intelligence, the weak, divided and kleptocratic Kabul government may not last for more than six months to two years. The expectation is that this buffer would compel the Taliban and their Pakistani backers to become more serious about a political settlement.

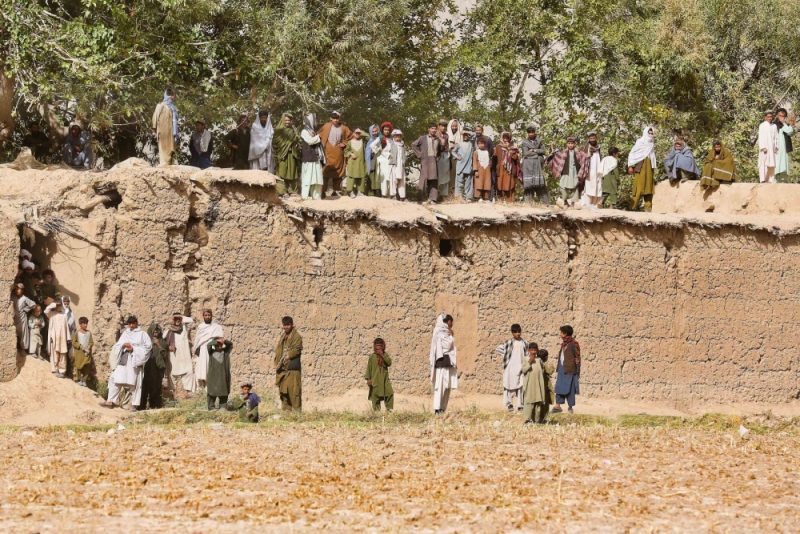

The second option points to the possibility of the government in Kabul collapsing sooner under the weight of both the ANDSF disintegrating and the Taliban rapidly advancing towards choking the major cities to surrender. The ANDSF is composed of personnel from various Afghan micro-societies, with a sense of loyalty to their ethnic and tribal stratum. Some have already defected or surrendered to the Taliban with their weapons. Meanwhile, the Taliban have lately made rapid territorial gains, taking over district after district across the country.

If the Taliban take power in Kabul, they are expected to rename the country as the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan and establish a strict theocratic order, more or less similar to what they had instituted during their previous rule (1996–2001).

However, the Taliban wouldn’t find it easy in any way to impose their writ across the country. The militia isn’t very popular, and its appeal doesn’t cut across numerous political and social cleavages in the country. Localised or regionalised deterrence forces have already started consolidating to fight it. The situation could descend into a devastating, multi-layered civil war, with Afghanistan’s neighbours and other regional actors scrambling for influence by backing different groups, as happened when the Taliban ruled.

It’s important to bear in mind that the Afghanistan conflict has been deeply entangled with many regional and extra-regional problems, including the Indo-Pakistan dispute, Pakistani–Saudi close relations, China–Pakistan strategic ties, Saudi–Iranian rivalry, Iranian–Pakistani distrust, as well as US–Russia and US–China contentions. General Austin Miller, commander of the US-led forces in Afghanistan, has said that ‘civil war is certainly a path that can be visualised … which should be a concern for the world’.

The third option is a negotiated political settlement for power-sharing governance and a transition to a general election for a popularly mandated government within a couple of years. Such a settlement can only work if it has the support of a cross-section of Afghanistan’s mosaic population and regional actors as well as the permanent members of the UN Security Council. Yet, the prevailing situation doesn’t inspire much confidence in this respect. The Doha peace process is stalled. The Taliban are enormously emboldened by their February 2020 peace agreement with the US, involving a ceasefire only with American and allied forces, and no political settlement, as well as by the total withdrawal of foreign forces by September. They have reasons not to be interested in a political settlement; they have already declared victory against the US and NATO and can see the trophy of power within their sights after two decades of fighting.

A Taliban triumph would also mean a boost for al-Qaeda, with which, according to UN reports, the militia still maintains close ties. If the key American and allied objective was to defeat the Taliban and al-Qaeda, whose 9/11 attacks triggered the US-led intervention, they can’t possibly claim to have succeeded.

At this stage, it’s hard to be optimistic about the chances of a settlement, as it may be too late. This is not to say, however, that urgent efforts shouldn’t be made by Afghan leaders within a framework of national unity and salvation, backed by the international community, to persuasively cajole the Taliban and their Pakistani sponsors to compromise in support of saving Afghanistan from more disaster. It is very disappointing to see that the leaders in Kabul are still divided, bickering over the formation of a state supreme council with the necessary executive power to make collective decisions about how to stymie the tide of the Taliban advances and give some certainty to the Afghan people about their future.

The current situation has already instilled panic and fear among citizens within the pervasive environment of violence and insecurity, causing an outflow of much-needed skilled workers and capital. Most people feel that they are caught between the self-centred and self-concerned leaders in Kabul and the very real prospects for the return of the Taliban to power. The threat posed by a Taliban return extends to fears that they will reimpose their discriminatory and brutal theocratic order, thus limiting the rights not only of women but of all citizens in general to a dignified and progressive life.

Yet, the only political settlement that might have a chance of success is one within a paradigm of interlocking national, regional and international consensus and enforceable by the UN Security Council. Failure to reach such a political resolution of the crisis should weigh heavily on Afghanistan’s leaders and the US and its allies.