China feels it no longer needs the foreign media—but it still can’t hide

After declaring a resounding victory against the Covid-19 pandemic, a newly confident China so far this year has tested new ballistic missiles, threatened Taiwan by ignoring the median line in the Taiwan Strait, expanded its erasure of Muslim Uyghur culture in Xinjiang, and extended its evisceration of Hong Kong’s autonomy and freedoms.

At the same time, China has shown a new aggressiveness in trying to curtail the activities of the foreign reporters in the country, and to quash any unfavourable coverage of the Chinese Communist Party or its leader, General Secretary Xi Jinping.

Where China once tolerated, even courted, the international media as a sign of the country’s re-emergence in the world, its leaders today see foreign correspondents as a meddlesome presence they can easily do without.

China has long been one of the world’s most restrictive countries for journalists, local and foreign. Reporters Without Borders lists China at number 177 out of 180 countries for its repression of the press, down just a few notches from 171st place a decade ago.

Foreign journalists in China have for decades faced restrictive visa procedures and expulsions, control of their movements, constant surveillance and physical threats. News assistants, the Chinese nationals who work as researchers and translators in foreign news bureaus, have routinely faced threats to themselves and their family members, invitations—or instructions—to spy on their employers, and warnings to ‘remember you are Chinese’. The situation for the overseas press corps in Beijing worsened dramatically after Xi came to power at the end of 2012, according to annual surveys by the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China.

But even by China’s dismal standards, this year has seen a marked deterioration.

At least 17 foreign reporters have been forced to leave China since the start of the year, an unprecedented mass expulsion and roughly double the number expelled in the first seven years of Xi’s rule. Even after the tumultuous events of 1989 with the Tiananmen Square massacre, only two American journalists, for the Associated Press and Voice of America, were immediately expelled.

Several other Western journalists now remaining in China have not had their press credentials renewed and are allowed to continue working only with short-term letters issued by the foreign ministry, meaning they can be expelled at any time. They are from CNN, the Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg News and Getty Images.

For the first time since the 1970s, Australian media outlets have no correspondents based in China. The Washington Post has had no correspondent in China since the last bureau chief left to take a new job in New Zealand and no visa has been granted for a replacement. The New York Times, which once had one of the largest and most prolific bureaus in China, now has a single foreign correspondent covering the vast country of 1.4 billion people.

Chinese officials have defended their actions as mere tit-for-tat retaliation for the treatment of its journalists overseas.

An earlier wave of expulsions of American journalists from China in May came after the Trump administration restricted the number of non-American journalists allowed to work for five Chinese state-run media outlets in the US to 100. Earlier this year, three Wall Street Journal reporters were forced out of China due to Beijing’s ire over an opinion piece that ran in the paper at the height of the coronavirus pandemic with a headline, ‘China is the real sick man of Asia’, that some Chinese considered offensive. The latest freeze on press credentials came after Trump signed an order restricting all Chinese journalists in the US to 90-day work visas, instead of the normal open-ended, single-entry visas they were accustomed to.

The last Australian journalists left China in dramatic fashion. After being visited by Chinese public security agents, Bill Birtles of the ABC in Beijing and Michael Smith of the Australian Financial Review in Shanghai first sought refuge in Australian diplomatic compounds and then flew out on 7 September. The visits seemed in retaliation for the June raids by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation on the homes of four Chinese journalists based in Australia. Those four Chinese reporters later fled back to mainland China. Later, Australia was told that Cheng Lei, a Chinese-born Australian citizen working for the state-run China Global Television Network (CGTN) had been detained in a national security case.

But beyond China’s expressed need for a retaliatory show of force in the world, its treatment of foreign reporters underscores an essential shift in the ruling communist party’s attitude over the past three decades; China feels it simply doesn’t need foreign journalists any more.

That is a marked change from the 1990s and the early 2000s.

Following the 1989 massacre at Tiananmen Square, China was anxious to end its global isolation, move on from the stain and demonstrate to the world its return to normalcy. Foreign journalists—while still subject to surveillance and heavy restrictions—were seen as conferring a kind of legitimacy on the regime. I travelled frequently to China from Hong Kong between 1995 and 1997, and many longtime reporters remember that as a ‘golden age’ of reporting, because of the relative openness. Foreign ministry officials regularly implored me to convince my bosses at the Washington Post to please add more correspondents to cover China.

Another period of relative openness for foreign reporters came in the years leading up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, when China’s leaders were anxious to showcase their country to the world. Many of the restrictions on foreign journalists’ ability to travel were lifted. Foreign correspondents could hire whomever they wanted as news assistants and researchers, instead of being assigned approved assistants from the foreign ministry. Foreign journalists were told they could interview anyone they wanted without seeking permission in advance. And internet censorship was relaxed, with many previously banned websites unblocked.

The explosion of the internet and popular Twitter-like Weibo blogs, beginning in around 2009, heralded another brief flourishing of media openness, and was a boon to foreign media coverage. Monitoring China’s unfettered online conversation became a key way for foreign correspondents to track public sentiment across the country, and served as an early warning system to reporters about pockets of unrest—farmers protesting against land seizures, villagers angry about polluting factories, and citizen journalists exposing local corruption.

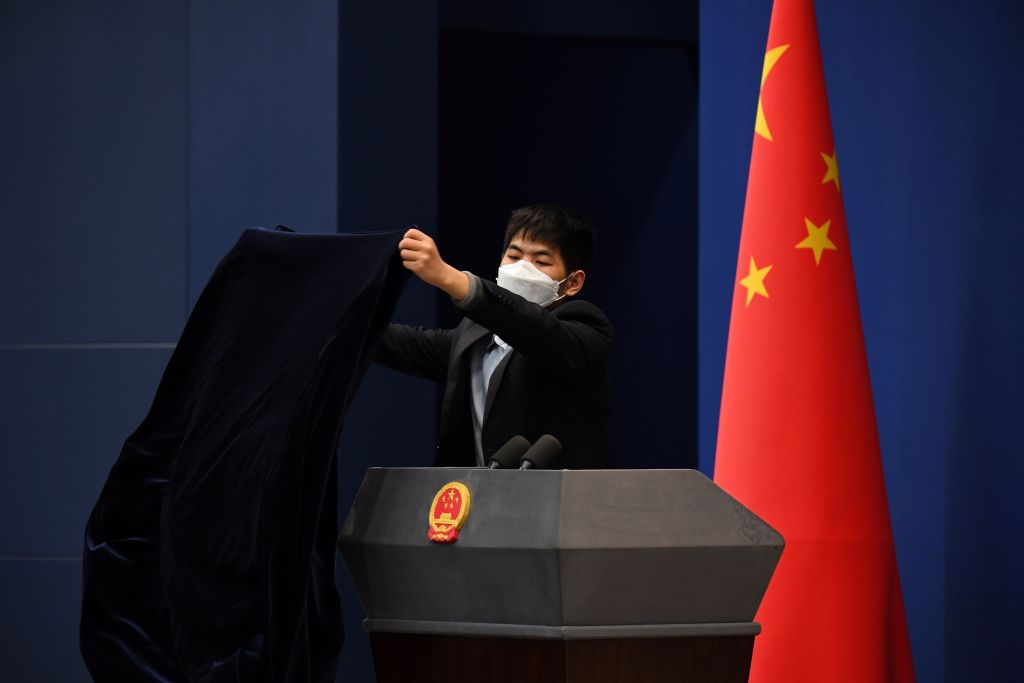

Foreign reporters were not only tolerated—we also became part of the show. During the largely ceremonial annual ‘two meetings’ of China’s National People’s Congress, the rubber-stamp legislature and the advisory body, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the local television cameras invariably swung to take images of foreign correspondents in attendance. Reporters on China Central Television always made note of how ‘even foreign correspondents’ covered the sessions.

China’s leaders always bristled at unfavourable or critical coverage. But in those days they looked to the presence of foreign correspondents for affirmation that China was getting the attention and respect it was due as a rising power.

China’s self-assured rulers now believe they no longer need the international media to promote China as a financial and investment powerhouse and to tell China’s story to the world. Its own global media reach has expanded, with the state-run news agency Xinhua now joined by China Daily, CGTN and others with bureaus and correspondents around the world producing Chinese propaganda in English. Chinese media outlets and institutions are active on Twitter (which is blocked in China) to disseminate the official line, directly bypassing foreign media gatekeepers.

In some ways, foreign media coverage of China appears to be reverting back to the days of the Cultural Revolution and before, when many Western journalists, collectively known as ‘China watchers’, were barred from the country and forced to monitor events from afar, from Hong Kong or Taiwan, by parsing Xinhua dispatches and interviewing fleeing refugees.

But China-watching today is different, and much more thorough. Even journalists banned from China can monitor Chinese media and the online space. Much of the reporting on the Uyghur concentration camps in Xinjiang was done from outside China, using satellite imagery and other computer-generated sources. Sources in Wuhan at the height of the pandemic posted videos of overcrowded hospitals and bodies unburied in the street. Outlets like Radio Free Asia and others do a commendable job of covering China by conducting telephone interviews with sources inside.

China may now want to expel foreign correspondents to control its own narrative and stem negative coverage. But its connectedness to the world means the country can no longer be isolated and escape critical coverage, no matter how much it tries.