The Quad was made for 2020

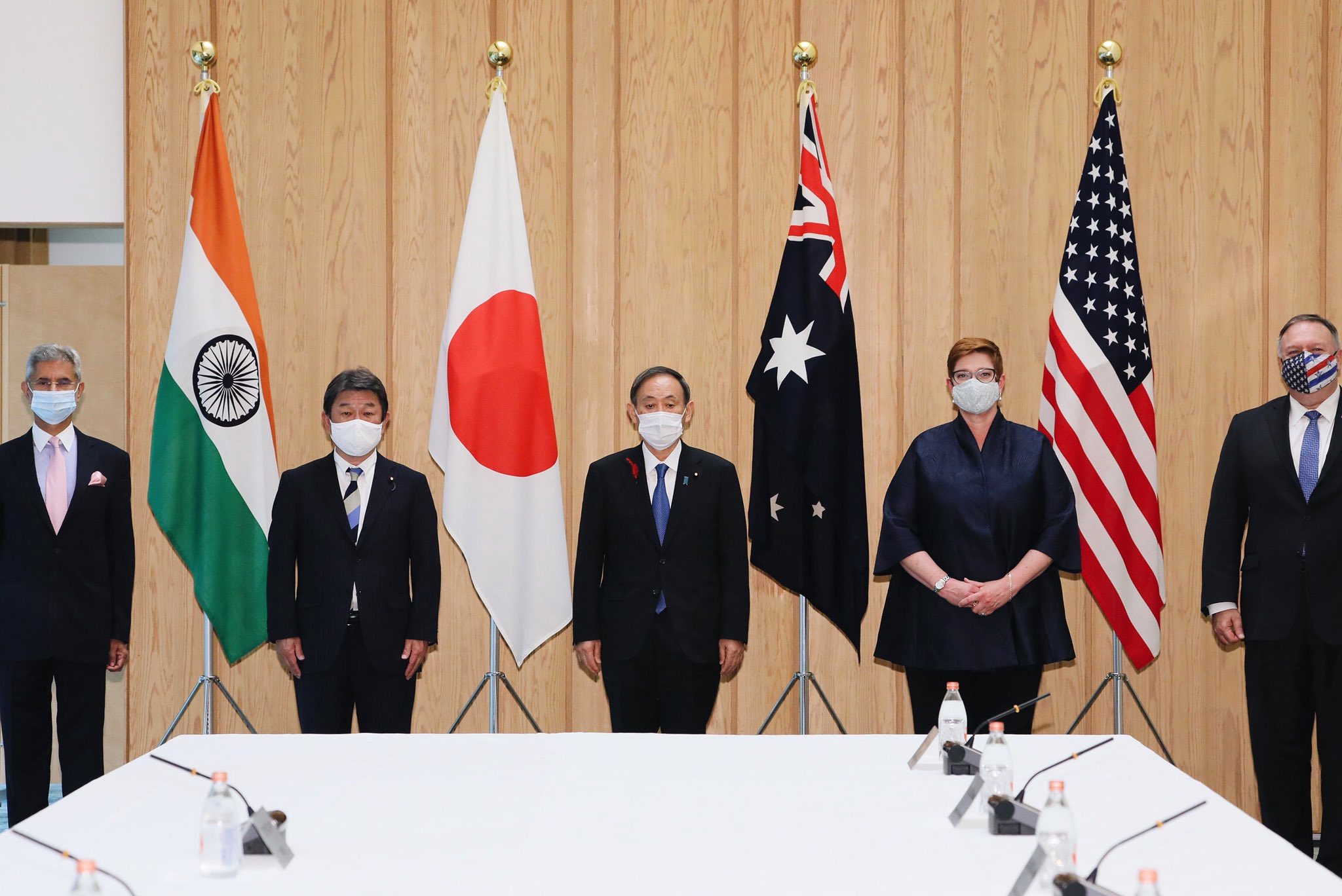

The ‘Quad’ meeting of Indian, Japanese, US and Australian foreign ministers in Tokyo earlier this week has resulted in the usual suspects saying the usual things.

China’s foreign ministry expressed outrage and called on these four countries not to get together, but instead to work in the spirit of win–win, mutual respect and common destiny—that is, they should let Beijing get on with business without being interrupted.

Critics of the Quad point to the members’ differing national positions as showing that the group can never amount to much. Others say it’s perhaps growing into a type of Asian NATO.

All this rather misses two larger points: Quad cooperation keeps strengthening and support for the worldview it stands for keeps growing. Tuesday’s meeting was its second high-level ministerial meeting—something that we’d been told couldn’t happen because of national sensitivities over China. And the appeal of a way of running international partnerships and governments that is free of coercion and use of force is getting more and more attractive as an alternative to the world offered by Beijing’s current leadership.

A lot of this is because the ‘China model’ and what it means for those of us not part of the Chinese Communist Party leadership’s family elites are becoming more and more obvious as 2020 wears on.

It turns out that former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe’s idea for the Quad’s security and economic ‘diamond’ of some of the world’s most capable democracies is better suited to the world of the 2020s than it was when he launched it back in the mid-2000s.

Why is that? Well, it’s because populations and leaders in the Quad countries are joined by the populations of countries in Southeast Asia and across Europe in a shared assessment that the leaders of the People’s Republic of China wish to wield its economic, technological, military and strategic power in ways that damage the interests of this large chunk of the world’s population.

Three polls tell us this. Data from the Lowy Institute’s April 2020 survey showed a collapse in Australians’ trust in China over the past two years. Singaporean think tank ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s State of Southeast Asia 2020 survey report, with pre-pandemic data from late 2019, showed that only 1.5% of respondents across the 10 ASEAN countries see China as a benign and benevolent power.

And this week, the Pew Research Center has released data gathered between June and August this year on the views in 14 developed countries from Europe, North America and the Asia–Pacific region showing a uniform collapse in these populations’ favourable views of China under Xi Jinping. China is viewed unfavourably by more than 70% of the populations surveyed in all but two of the 14 countries, with young people sharing this assessment or being even more critical (for example, in South Korea). That’s an inversion of sentiment from 10 years ago, and much of the slide happened in 2020.

Interestingly, as an individual leader, Xi shares a very large unfavourable rating with US President Donald Trump, but China is distinguished from America by the fact that, unlike Trump, Xi is a product of a permanently ruling party. So it’s very likely that the growing concerns about China will endure while Xi remains leader of the CCP.

What’s worse for Beijing is that this isn’t about any particular bilateral relationship going bad, where the fault is as much on one side as the other. It’s a pretty uniform collapse in Beijing’s soft power that has correlated with China’s assertive and belligerent actions over the past year, built on a solid track record of coercion before then.

This matters because governments outside the authoritarian world tend to go where their populations lead them on general policy—and the populations across the Indo-Pacific, Europe and North America are looking rather consistent in wanting alternatives to a world or region dominated by the kind of Chinese state we see now.

The Quad members are promoting an Indo-Pacific free from coercion where sovereign states can cooperate for prosperity and security, which looks like an approach with rising popular support not just in the Indo-Pacific, but in large swathes of the world’s most capable and prosperous economies.

That groundswell in public sentiment provides a foundation for government action, and for economic reconfiguration away from the nasty dependencies we developed on operating in and through the jurisdiction governed by the CCP.

This takes us well beyond needing to parse the public statements of the four foreign ministers at the meeting to see the direction of cooperation. It also lets us know that as long as China continues on the path Xi has set for it, Quad cooperation will deepen, and partner countries across the region and the wider world will quietly welcome this, buoyed by popular support.

So, we’ll see more meetings and more quiet but substantial cooperation on topics like managing the pandemic, maritime security, countering disinformation and cyber hacking, and rebuilding economies in a post-Covid-19 world in ways that remove vulnerabilities and sovereign risks from overexposure to Beijing’s jurisdiction. All accompanied by more strident voices in Beijing wishing none of this was happening. That’s proving to be a virtuous circle.