The strange submarine saga: the industry policy puzzles

Australia has spent 40 years building its own submarines.

For subs (and ships) we do defence as industry policy. Build our own naval muscle and build our economy. Protect sovereignty and protect jobs. The capability must have Australian content.

Today’s vogue phrase is ‘sovereign industrial capability’, a concept hammered at with more than 30 references in the 2020 defence strategic update and force structure plan.

The Covid-19 pandemic has given new meaning to the defence discussion of the need for a robust and resilient industrial base.

We don’t necessarily have sovereign industrial capability in priority areas, but we’re sure planning to get it—or regain what we’ve lost. Australia now proclaims the need to ‘have access to, or control over the skills, technology, intellectual property, financial resources or infrastructure that underpin the Priorities [for industrial capabilities]’.

So, after 40 years on the subs journey—and much longer on the ships—we’re still struggling for the sweet spot where defence need and industry policy unite.

The struggle makes for passionate politics, proving that in the phrase ‘political consensus’ keep your eye on the politics. Because the submarines are vital yet vexed, the subs consensus is a hull undergoing repeated pressure tests.

In the struggle over building the new Attack-class submarines in Australia or overseas (Customer Oz versus Industry Oz) the industry side finally triumphed. It was, though, a close-run thing.

Malcolm Turnbull took industry policy to a rich new place with the largest ever peacetime defence industry investment program. In his memoir, the former prime minister argues the case for an Australian-built submarine:

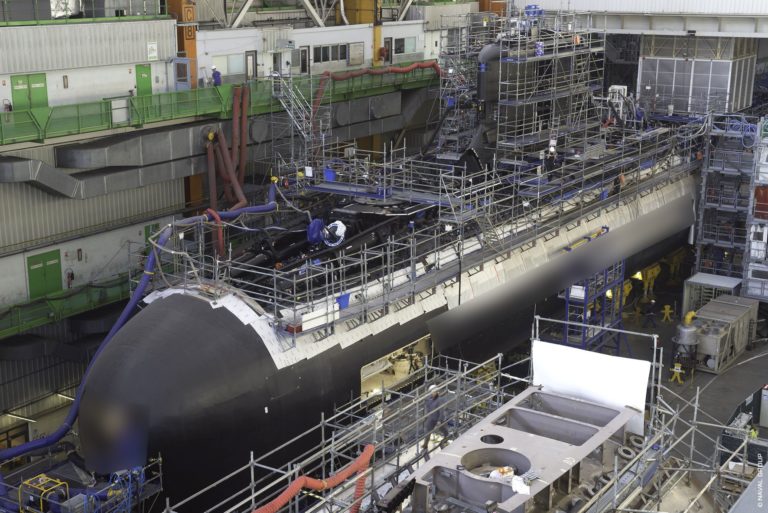

Certainly, a foreign yard with current experience in building submarines will build faster and at less cost than an Australian yard would build the first one—but stress ‘the first one’. We’ll never have a sustainable continuous shipbuilding industry unless we start building ships and do so continuously. And if we want, over the decades to come, to develop an Australian advanced manufacturing sector, there is no industry more likely to provide the ‘pull-through’ stimulus than defence, and no project more at the cutting edge than submarines—the most complex, sophisticated and lethal vessels in the fleet.

Turnbull’s minister for defence industry and then defence minister, Christopher Pyne, says the vision is ‘to remake our strategic industrial base through the Australian defence industry’.

Because it’s about defence industry—not just industry—a Liberal government adopted what Pyne calls ‘an uncharacteristically European dirigiste demonstration of government intervention in the market’.

Pyne says the continuous shipbuilding program of the naval shipbuilding plan is the most detailed long-term guide for defence industry in Australia’s history: ‘A drumbeat of new vessels at least every two years for decades is something Australia has never enjoyed before.’

The new force structure plan calls for the acquisition or upgrade of up to 23 classes of navy and army maritime vessels. Cost: $168–$183 billion. Schedule: Out to the completion of the Attack subs in the 2050s.

The Turnbull government dived into the defence industry task with what Pyne describes as a combination of the PM’s ‘enthusiasm and my overconfidence’. Pyne’s jest is more revealing than he intends on the shambles of making up industry policy as you go along and on the run.

The submarine saga is strewn with missed options and strange turns: Labor’s lost six years, the death of the car industry, Tony Abbott’s dash for a Japanese-made sub.

The Rudd and Gillard governments proclaimed the need for 12 new submarines but didn’t get going. Those were the new-subs-stasis years. Labor’s focus was on fixing the Collins class and fixing the budget.

Labor, ultimately, left the sub choice to the Abbott government. Governments can’t bind future governments, but they can make big decisions that define the landscape and set the tide. Because of its new-subs stasis, Labor made no such decision.

Abbott wanted to build the frigates and offshore patrol vessels in Australia but buy the subs from Japan. Abbott’s government was willing to do some defence industry policy (yes to ships, no to subs) but baulked at industry policy: keeping the Oz car industry was dismissed as dire, dismal demi-dirigisme.

The Abbott government centralised shipbuilding in two cities, Adelaide and Perth (sorry, Melbourne), but would do nothing more for our last two car manufacturers.

A few mad moments of macho mocking from Canberra did much to hasten the departure of Holden and Toyota. In today’s sovereign capability era, Canberra would be hugging the final two carmakers, not hissing them out the door.

In the hierarchy-of-needs chart for defence industry, submarines and planes sit near the top of the triangle, supported by a broad array of complex manufacturing abilities (science and skills, investment and research). Losing cars from the hierarchy kicked out much that an advanced industrial economy needs to make its own ships and subs.

Australia will pump hundreds of billions into building and sustaining sovereign industrial capacity for defence, but in 2014 we wouldn’t stump up $150–$250 million to keep car manufacturers till 2022. Instead, an industrial extinction event.

A lot of jobs gone. A lot of capability lost.

The decisive ‘Yes’ of today’s defence industry policy contrasts with the derisive ‘No’ to industry policy just a few years back.