Attack on media freedom in Malaysia demands Australian response

Malaysia’s attack on journalists employs old methods with nods to current fashion.

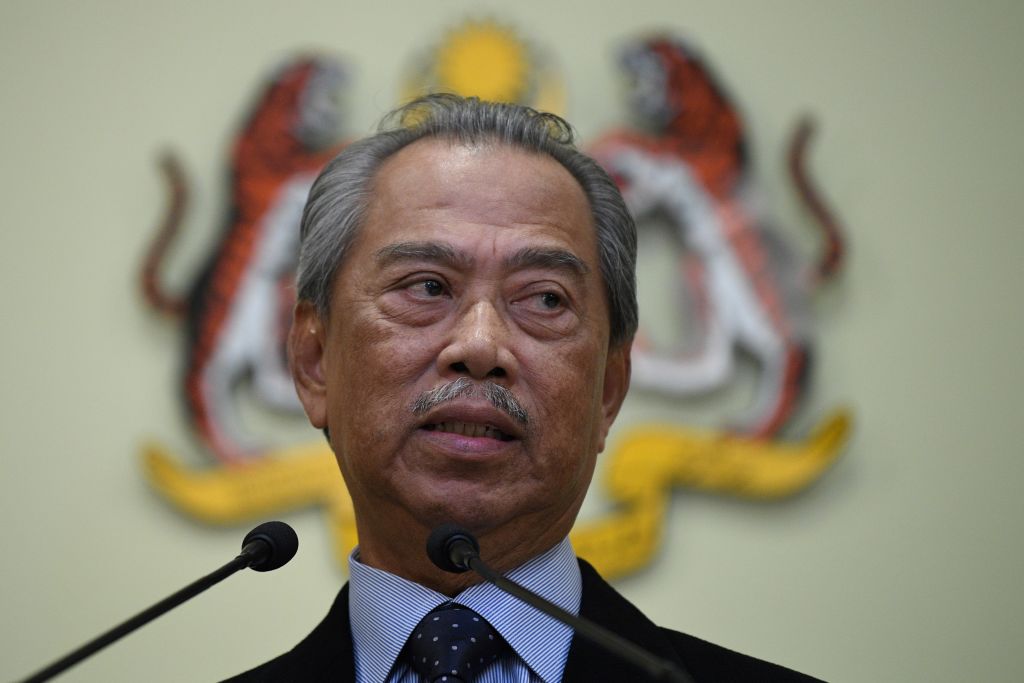

Clinging to power with a razor-thin majority, the government that snatched office in March brandishes a dictatorial bludgeon to batter the media.

The purpose is to cling to power and galvanise conservative voters. One tactic is to control and intimidate journalists.

The crackdown uses Malaysian instruments with elements of Trumpian ‘fake news’ and dollops of Duterte. Malaysia adopts the media repression and authoritarianism that are a new normal in the Philippines.

Malaysia’s elite needs all the distractions it can generate. Former Prime Minister Najib Razak is convicted of abuse of power, breach of trust and money-laundering and sentenced to 12 years’ jail. Najib remains a member of parliament and is one vote of that slim majority.

A king of kleptocracy falls while the old kleptocracy rises again, wielding power in ways both cynical and ruthless, stirring the ingredients of contempt, sedition and insult to Malaysia.

- The editor-in-chief of Malaysiakini, Steve Gan, awaits judgement after facing contempt-of-court charges. The case against a beacon of modern Malaysian journalism (and modern Malaysia) could have a ‘chilling effect’.

- Six journalists (five of them Australian) are interrogated by Malaysian authorities, accused of sedition and defamation, over an Al Jazerra documentary on migrant workers in Kuala Lumpur. Good journalism that discomfits the government is treated as a seditious attack on the state.

- A book of analysis and reportage on Malaysia’s 2018 election, Rebirth: Reformasi, resistance and hope in New Malaysia, is banned, copies are seized, and eight writers who contributed are questioned by police.

Rebirth describes a seminal moment in Malaysia’s democracy: the first time the voters changed the government. That’s history the old team reborn wants to erase, issuing a government gazette pronouncing the book ‘absolutely prohibited throughout Malaysia’ because it was deemed a publication ‘which is likely to be prejudicial to public order, which is likely to be prejudicial to security, which is likely to alarm public opinion, which is likely to be contrary to any law and which is likely to be prejudicial to national interest’.

Most of Rebirth’s material was initially published by New Mandala, at the Australian National University, in its coverage of the 2018 election. The New Mandala reporting and Rebirth were edited by an outstanding Australia-based journalist, Kean Wong. As New Mandala says, what’s at stake here is open and democratic discussion: ‘We urge Malaysian authorities to refrain from any activities that indicate a lack of respect for academic and journalistic freedom in Malaysia.’

When reviewing Rebirth in May, I commented that kleptocracy takes a lot of killing. It’s a cynical comment for a cynical moment, but cynical calculation has its uses. Perhaps calculation will mean the Al Jazeera six and the contributors to Rebirth won’t face court.

The political interest is to keep this simmering, not boiling over. The bludgeon is a blunt tool that delivers political benefits just by being brandished: excite and enrage the voters, deter and direct the media.

The attack on journalism—and Australian journalists—has a faint echo of the 1980s and 1990s, when Mahathir Mohamad, Lee Kuan Yew and Suharto deployed ‘Asian values’. The leaders told Asian reporters to bow to authority and hierarchy while Western journos should respect distinctive Asian systems.

Back then, it made sense for Southeast Asian governments to berate Oz hacks. It was far safer than attacking US media, which could bring down righteous First Amendment anger from Washington and inflict real pain. Today, unfortunately, bashing journalists is a Trump trademark.

There are no distinctive Asian values involved this time. Just the strident authoritarian and nationalist script being used at full volume in multiple capitals around the world.

What Malaysia is doing to Malaysian and Australian reporters tests the relationship between Canberra and Kuala Lumpur.

Australia is an old friend, and an ally through the one-way security guarantee to Malaysia and Singapore, which marks its 50th birthday next year. More than anywhere else in Southeast Asia, the Old Mates Act applies: Canberra can speak truth in Kuala Lumpur (and Singapore) based on history and habit. That tough, continuing conversation might happen in private, but habit and history say it should be happening.

Publicly, Australian support for journalism must be part of our international engagement. We face an era of disinformation, coercion and grey-zone activities in a ‘more competitive and contested region’.

Journalism is a great antidote to lousy information. Good reporting is where facts and open argument attack the grey nasties. If you want transparency and accountability, let loose a bunch of hacks. Dictators detest headlines they can’t control. Authoritarians hate hard questions when microphones mass. Media are the loud, messy bit of democracy at work.

Beyond giving proper support to journos under attack, standing up for journalism advances Australian interests and influence as well as values.

The script Canberra could use has been rehearsed in a letter to Malaysia’s Star newspaper by Australia’s high commissioner to Kuala Lumpur, Andrew Goledzinowski. He attacked a Star article that used lots of shrill quotes from China’s state-run Global Times paper to argue Australia’s icy relationship with China is because of Canberra’s ‘hostile attitude’. Goledzinowski’s letter concluded:

At the end of the day, Australia cannot control what other countries do. We will continue to uphold our values and principles, and continue to do what we believe is right for Australia and the world. If a side effect of that is coercion and disinformation, then that is unfortunate. But we are not the first country, nor probably the last, to experience it. Perhaps it is actually Australia who has stopped ‘turning the other cheek’.

The argument Australia offers to Malaysia about journalism will be about values and principles. But it’s also a practical discussion of what works to strengthen a democracy and a nation. A troubled and desperate government needs to hear that from a concerned friend.