Satellite images show positions surrounding deadly China–India clash

The recent deaths of at least 20 soldiers along the contested border at Ladakh between India and China represents the largest loss of life from a skirmish between the two countries since the clashes in 1967 that left hundreds dead. It also highlights the tensions that have been building along the Line of Actual Control since early May.

Using this satellite imagery, I will try to illustrate the approximate reality on the ground. My analysis disproves some of the more extreme claims that have been made about the incident, such as that thousands of Chinese soldiers have crossed the LAC and encamped in Indian-controlled territory. The satellite pictures also highlight the obvious threats to a peaceful status quo that exist along the western sector of India’s border with China.

The analysis includes evidence that strongly suggests People’s Liberation Army forces have been regularly crossing into Indian territory temporarily on routine patrol routes.

The details of this week’s clashes are still murky. But based on recent satellite imagery and media reporting, it appears the bulk of casualties were the result of soldiers falling during hand-to-hand fighting along a steep ridgeline that marks the LAC. The small area that is at the heart of this dispute appears to straddle the LAC and likely houses less than 50 Chinese troops.

Neither Beijing nor Delhi considers the loosely demarcated line that separates the two countries in Ladakh to be an authoritative border. It approximates areas of territorial control established at the end of the 1962 Sino-Indian War when China withdrew from much of its captured territory on the Himalayan plateau.

The border standoff at Ladakh has become a politically charged issue in India. The Indian government has revealed few details about the situation over the past few weeks. Former Indian Army officers, however, have been providing information to journalists and the media have been consistently painting a picture of a substantial conflict, often involving claims of the incursion of 10,000 PLA troops into undisputed Indian territory.

The reality is less dramatic, but does represent a significant change to the status quo along the India–China border that threatens to escalate.

By analysing satellite imagery from late May and early June it’s possible to make informed judgements about the positions of forces at multiple hotspots.

Along the India–China border there are three key areas that produce the majority of tension between the two countries: Arunachal Pradesh; Sikkim and nearby Doklam (the site of a major skirmish in 2017 that saw Indian troops enter Bhutanese territory to prevent the completion of a strategic road being built by China); and Ladakh.

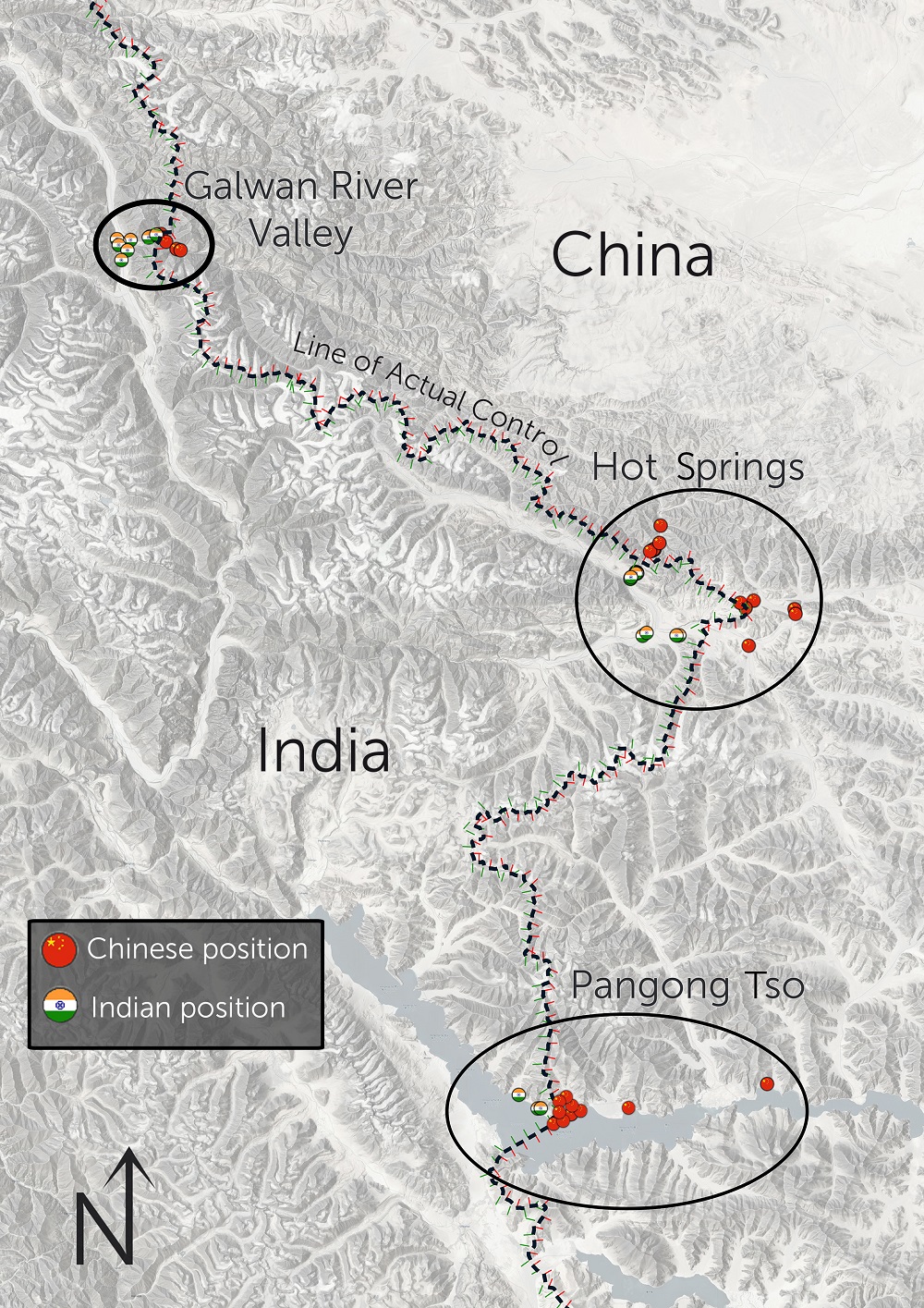

The build-up of troops and military positions in recent months has been mostly in the Ladakh sector. Developments have occurred in three strategic areas along the LAC: the Galwan River Valley, where this week’s deadly clashes occurred; Hot Springs, where satellite evidence suggests that Chinese forces have regularly entered Indian territory; and the Pangong Tso.

In all these key areas, both sides have steadily built up troop numbers and military positions close to the LAC (see map 1).

Map 1: Ladakh sector, showing Line of Actual Control and key areas

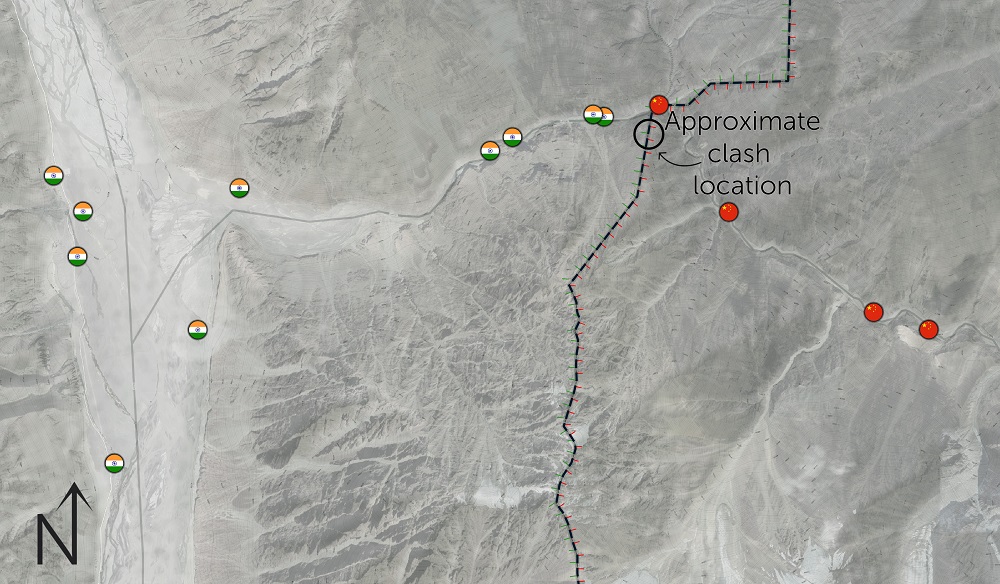

The most significant hotspot right now, where prior to disengagement Indian and Chinese troops were positioned within a few hundred metres of each other, is in the Galwan River Valley. Until May, the PLA didn’t have positions within the valley, despite several kilometres being on the China-controlled side of the LAC. However, recently established Indian positions closer to the LAC, and the construction of a road to supply these positions, appears to have prompted the PLA to establish a number of significant positions and move up to 1,000 soldiers into the valley.

China is reportedly now laying claim to all of Galwan River Valley.

One key position, referred to in the media as Patrol Point 14, is a sandbank along the LAC that has been occupied by a small number of tents and likely fewer than 50 Chinese soldiers. India and China had reportedly agreed that this position would be dismantled as part of efforts to defuse tensions between Indian and Chinese forces. The move to dismantle the camp is apparently what sparked the recent deadly clashes.

The disposition of forces in this area is shown in map 2.

Map 2: Galwan River Valley, showing approximate location of clash

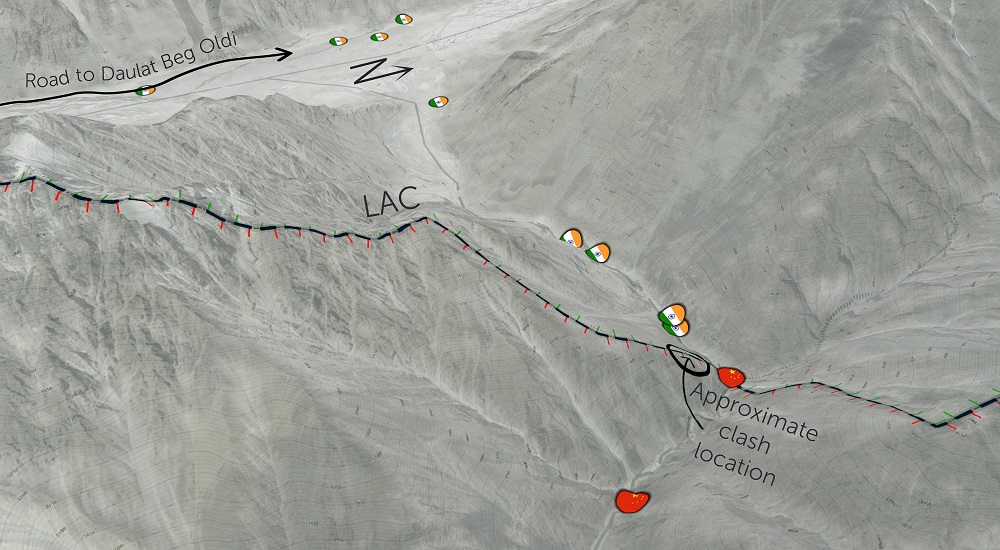

Strategically, the PLA’s advances into the Galwan River Valley provide a superior vantage point for observing a supply route used by the Indian Army to reach its northernmost base, and the world’s most elevated airfield, Daulat Beg Oldi.

From ridgeline positions, PLA forces would be able to monitor all traffic on the recently completed Darbuk–Shyok–Daulat Beg Oldie road, a strategic route that abuts the LAC through much of Ladakh and has taken nearly 20 years to build. Additional Indian military bases have been constructed along this road recently. An oblique view of the Galwan and Shyok valleys is shown in map 3.

Map 3: Galwan River Valley, oblique view of approximate location of clash relative to road to Indian military base

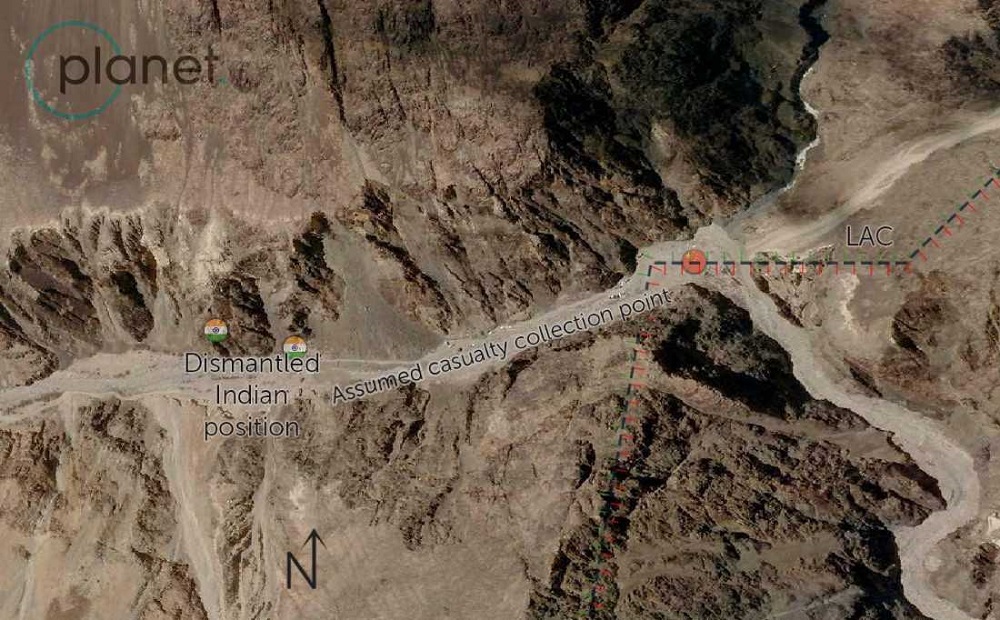

Satellite imagery provided by Planet Labs taken on 16 June, the morning after the deadly clash along the LAC, shows both the Indian and Chinese forwardmost positions that had been dismantled over the past week (maps 4 and 5). A temporary Indian position (likely a casualty collection point), however, had been set up within 50 metres of the LAC (map 4). In addition, a group of around 100 trucks can be seen on the Chinese side of the border near other positions in the valley (map 5). It’s not clear if these trucks are reinforcing the area with troops or dismantling positions in accordance with the disengagement agreement between India and China.

Map 4: Galwan River Valley, showing dismantled and temporary Indian positions, 16 June 2020

Satellite image from Planet Labs.

Map 5: Galwan River Valley, showing partially dismantled Chinese position and trucks, 16 June 2020

Satellite image from Planet Labs.

South of the Galwan River Valley lie two other significant hotspots, the Hot Springs area and the Pangong Tso.

In Hot Springs, most of China’s development of infrastructure and forward positions since 2019 has taken place near a locality called Gogra, roughly 10 kilometres northwest of the Hot Springs outposts. In April 2019 a new road was constructed to the Chinese hamlet of Wenquan, roughly 7 kilometres north of the LAC. Since then, there has been a significant military build-up along the river valley towards the LAC, with the nearest permanent Chinese position within 1.8 kilometres of the LAC.

Satellite imagery from late May shows significant developments closer to the border (map 6). From the forwardmost positions, there’s a clear dirt track that crosses almost 1 kilometre into Indian-controlled territory. There is also a second, looped dirt track that crosses nearly 500 metres into Indian-controlled territory; the fact that it’s a circular track suggests that it may be a regular patrol route. There are no PLA positions on the Indian side of the LAC; however, these tracks suggest that PLA forces are regularly making incursions into Indian territory, at a remote part of the LAC that is 10 kilometres from the nearest Indian positions.

In response to this, India has begun constructing a large, permanent position on its side of the LAC, but along the river valley in a position that overlooks the LAC, presumably to prevent any further incursions by PLA forces into Indian territory.

Map 6: Hot Springs area, showing position of developments between Gogra and Wenquan, May 2020

These developments seem to have occurred peacefully, with no media reports of skirmishes. Indian Army sources refer to the successful, but limited, disengagement of Indian and Chinese troops in the Hot Springs area. The distance between the forwardmost positions of the PLA and the Indian Army in the area is much greater than in the Galwan River Valley.

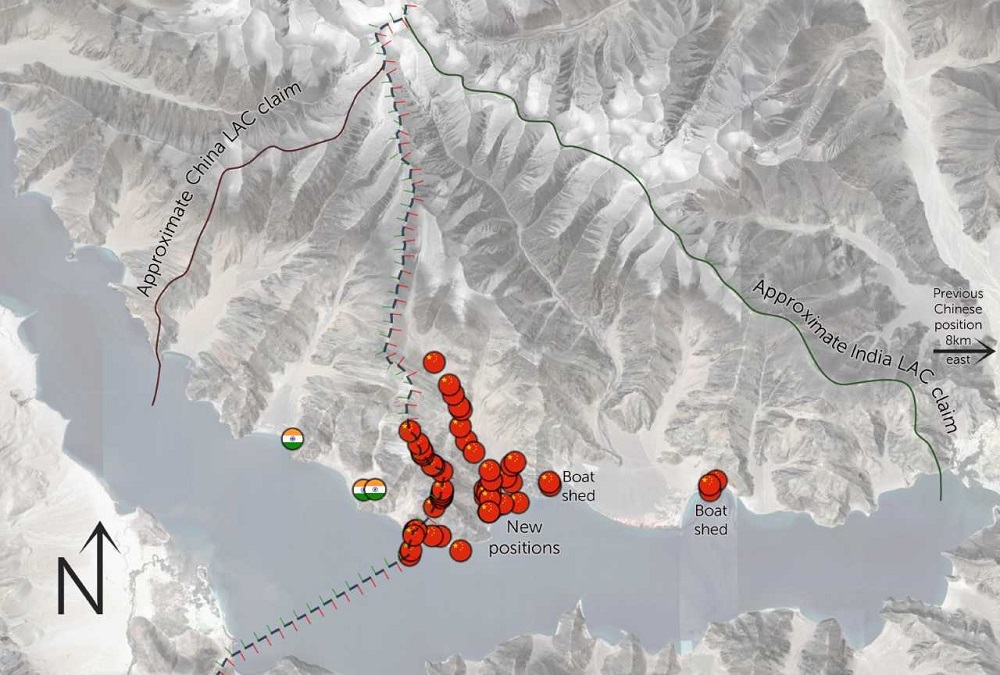

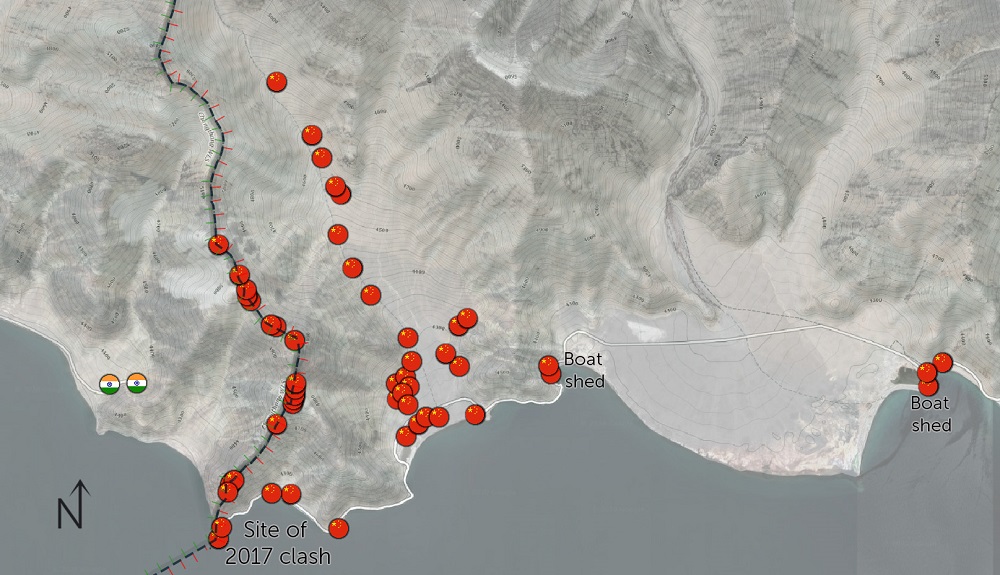

The third significant hotspot in Ladakh is the Pangong Tso, an alpine lake over 100 kilometres long that is bisected by the India–China border. This area is the site of the most significant divergence between New Delhi and Beijing on the precise location of the border, differing by up to 30 kilometres. A number of peninsulas (known as fingers) mark the named features of the lake, with China claiming territory up to finger 2, and India claiming territory up to finger 8 (map 7).

Map 7: Pangong Tso, showing Indian and Chinese positions and claims relative to Actual Line of Control

India has had permanent positions within the disputed area (between fingers 3 and 4) for at least 10 years and expanded its presence in the disputed area in 2015–16. China kept its permanently stationed forces outside of the disputed territory until May.

In the past month, Chinese forces have become an overwhelming majority in the disputed areas. Significant positions have been constructed between fingers 4 and 5, including around 500 structures, fortified trenches and a new boatshed over 20 kilometres further forward than previously. More structures appear to be under construction.

The scale and provocative nature of these new Chinese outposts is hard to overstate: 53 different forward positions have been built, including 19 that sit exactly on the ridgeline separating Indian and Chinese patrols.

In 2017, footage emerged showing a significant clash between Indian and Chinese troops at finger 4 of the lake. The beach shown in the footage has, since May, been permanently occupied by PLA troops with a garrison of around 20 structures.

A detailed view of the new Chinese positions is shown below.

Map 8: Pangong Tso, showing new Chinese positions

In all hotspots along the Ladakh sector of India’s border with China, both sides have engaged in significant efforts to build up their forces in forward positions and alter the status quo along the LAC.

This week’s deadly skirmish shows that the situation is extremely volatile and introduces the possibility of escalation along the border regions. It could act as a shock to policymakers in the region and spur them to push for more genuine and meaningful disengagement to prevent further loss of life. But it could also spark a larger confrontation between the two nuclear-armed powers that could escalate into a major conflict.