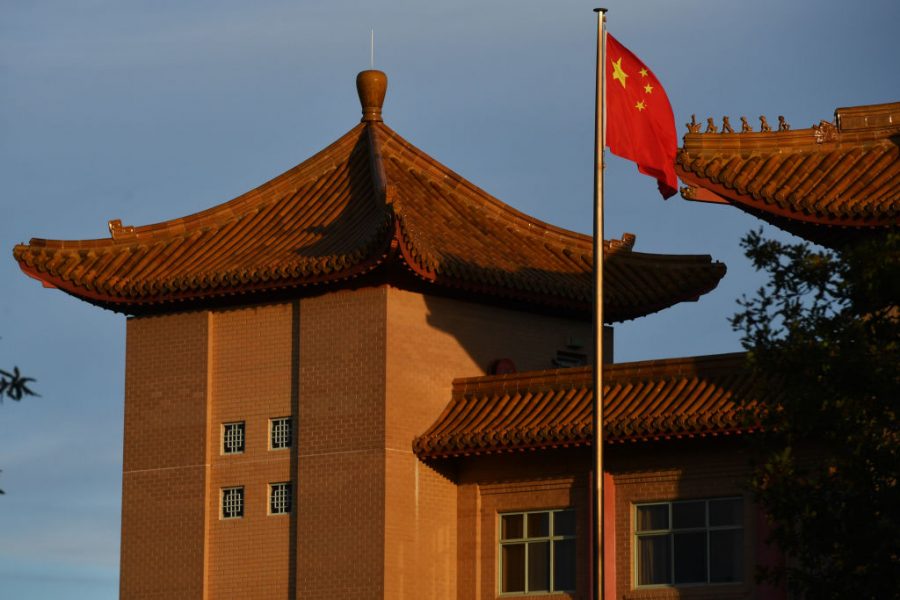

Chinese diplomats behaving badly

Chinese diplomats have long had a reputation as well-trained, colourless and cautious professionals who pursue their missions doggedly without attracting much unfavourable attention. But a new crop of younger diplomats are ditching established diplomatic norms in favour of aggressively promoting China’s self-serving Covid-19 narrative. It’s called ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy—and it’s backfiring.

Shortly before the Covid-19 crisis erupted, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi instructed the country’s diplomatic corps to adopt a more assertive approach to defending China’s interests and reputation abroad. The pandemic—the scale of which could have been far smaller were it not for local Wuhan authorities’ early mistakes—presented a perfect opportunity to translate this directive into action.

And that is precisely what Chinese diplomats have been doing. For example, in mid-March, the foreign ministry’s newly appointed deputy spokesperson, Zhao Lijian, promoted a conspiracy theory alleging that the US military brought the novel coronavirus to Wuhan, the pandemic’s first epicentre.

Similarly, in early April, the Chinese ambassador to France posted a series of anonymous articles on his embassy’s website falsely claiming that the virus’s elderly victims were being left alone to die in the country. Later that month, after Australia joined the United States in calling for an international investigation into the pandemic’s origins, the Chinese envoy in Canberra quickly threatened boycotts and sanctions.

But, unlike the fictional special-operations agents after which they’re named (from a popular Chinese action movie), China’s wolf-warrior diplomats haven’t been rewarded for their recklessly confrontational style. Far from burnishing China’s international image and placating those who blame the country for the pandemic, their actions have undermined China’s credibility and alienated the countries it should be wooing.

Why change tack in the first place? One reason is China’s current combination of historical insecurity, rooted in its so-called century of humiliation, and heady arrogance, fuelled by its immense economic clout and geopolitical influence. So keen are China’s leaders to gain the respect they feel their country deserves that they have become highly sensitive to criticism and quick to threaten economic coercion when countries dare to defy them.

Another reason is the current regime’s emphasis on political loyalty. Under President Xi Jinping’s highly centralised leadership, Chinese diplomats are evaluated not on how well they perform their professional duties, but on how faithfully and vocally they toe the party line. This is exemplified by the appointment last year of Qi Yu, a propaganda apparatchik with no foreign policy experience or credentials, as party secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs—an important post traditionally held by an experienced diplomat.

If aggressively pushing the Chinese Communist Party’s preferred narrative is a matter of professional survival, diplomats will do it, even if they recognise that it’s counterproductive (as many probably do). They certainly won’t try to persuade their political masters to change course. Whereas diplomats risk paying a heavy price for conscientious dissent, they seem to suffer no consequences—from criticisms in official media to demotions or dismissals—for destructive loyalty. When pushing the CCP-approved narrative produces negative results, it is, in party parlance, an issue of tactics, not the ‘political line’. Punishing loyal diplomats for ‘tactical errors’ would make them more reluctant to do the CCP’s dirty work in the future.

By removing any incentive for diplomats to temper their approach and offering a convenient excuse for setbacks, this logic entrenches bad policy. It doesn’t help that China lacks a free press and political opposition to highlight the failures of the wolf-warrior approach. Unlike Western diplomats, those in China don’t have to fear public ridicule or criticism. All that matters is what their bosses say—and their bosses want wolf warriors.

This is a mistake. At a time when China’s reputation is suffering and its relationship with the US is in freefall, the country’s diplomats should be focused on differentiating China’s foreign policy from that of US President Donald Trump.

It is Trump who recklessly promotes conspiracy theories and aggressively responds to any perceived slight with threats and sanctions. It is Trump who foolishly alienates friends and partners, rather than cultivating mutually beneficial relationships. And it is Trump whose belligerent insistence on his country’s superiority has eroded its international reputation and undermined its interests.

China’s leaders should know better.