Not much dialogue at Shangri-La

The 18th iteration of the Shangri-La Dialogue, the region’s premier defence and security conference, was much anticipated. The Sino-American trade dispute had stepped up with Washington imposing tariffs on a further US$200 billion worth of goods and Beijing returning the favour. Acting defence secretary Patrick Shanahan would be presenting his first major policy address in the region and the Pentagon had promised that the speech would flesh out the defence contribution to the administration’s ‘free and open Indo-Pacific strategy’. Given the increasingly hardline rhetoric of Trump administration officials towards China since Vice President Mike Pence’s Hudson Institute speech, the opening US plenary promised potential fireworks.

Not to be outdone, Beijing chose this year to re-engage with Shangri-La. Since 2014, when Lieutenant General Wang Guanzhong went off script and complained about an atmosphere ‘suffused with hegemonism’, China has sent low-level delegations reflecting a suspicion that the forum is rigged against it. This time it would be the defence minister going, giving Beijing a protocol edge as he technically outranked Shanahan.

In the Chinese system the ministerial role is a state position, and often just a figurehead; the real power lies with the party officials who control the military. Wei Fenghe is a general in the People’s Liberation Army and the fifth-ranking member of the Central Military Commission, a party man of genuine substance. Brendan Taylor and I anticipated that this move was part of the country’s broader efforts to position itself as a stabilising force in the region and so we thought it was likely that China would use the opportunity of the plenary address at the dialogue to pursue a strategic charm offensive.

We were expecting fire and brimstone from the US and smooth diplomacy from China but got almost the reverse. Shanahan presented a remarkably moderate, almost boring, address. It was as if there’s a template for Shangri-La addresses on some laptop in the Pentagon which is tweaked from year to year. There was nothing new added to existing policy and even the formal Indo-Pacific strategy document, which was released online as the acting secretary spoke, had little of substance that was new. And when pressed in question time, Shanahan essentially said, this time there’s money attached, about which more than a few had doubts.

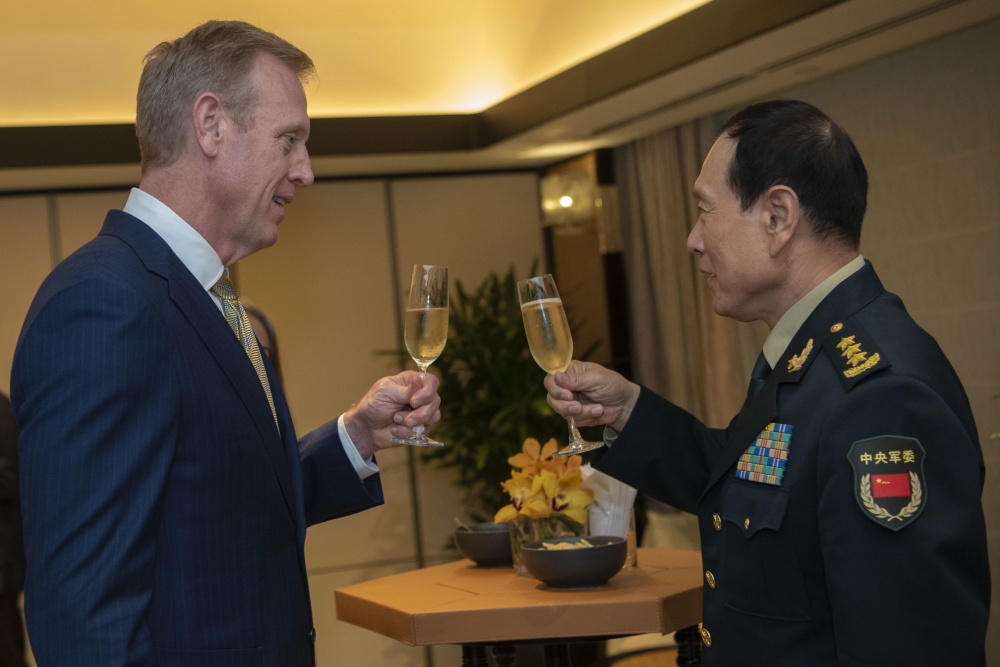

While there was a subtle dig at China as he described presenting the Chinese minister with a coffee-table book of photos of Chinese vessels transferring oil at sea the previous day, referring to China’s efforts to help North Korea avoid sanctions, in contrast to the Manichaean tone of Pence and others, Shanahan was positively placatory. Indeed, in talking about areas the two could work together he held out a hand to China.

If the US was more conciliatory than we expected, the confident and indeed pugnacious remarks of China’s defence minister were even more surprising. Wei unapologetically laid down China’s vision for the region and the Chinese Communist Party’s version of its history. China was not an aggressive power, claimed the minister, never having invaded ‘another inch’ of any other country. The splutters from Vietnamese and Indian delegates could not be missed. As Ashley Townshend from the University of Sydney put it, the address asked for acceptance of China’s broader strategic claims and implied that in return it would remain peaceful.

But it was in the question session that Wei most surprised. Where Shanahan seemed uncomfortable and keen to get off the stage, Wei was unflappable, happy to address all questions and even, in a distinctly PLA way, charming. When questions came about Tiananmen and Xinjiang, alongside more straightforward questions about capabilities and a South China Sea code of conduct, he dealt with them directly. While his arguments were themselves standard party-line stuff—Tiananmen was a turbulent period, the right decision was taken and 30 years of prosperity is the proof—but seeing a four-star general recount them in the full glare of a packed hall and the international media was something to behold. The level of Chinese confidence embodied by the general was the talk of the conference halls.

What of the lesser powers? Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s keynote opening the dialogue was a deft piece of diplomacy. The fact that delegates from China and the US seemed equally annoyed by it is perhaps testimony to his ability to thread his particular needle. The unmistakable, although unstated, point Lee made was that countries in the region see China with more pragmatic eyes than does Washington. And the inability of US officials and delegates to come to terms with that fact was striking.

Shangri-La also marked the first outing on the global stage of Australia’s new defence minister, Linda Reynolds. She opened with a cringe-inducing reference to mateship, but like Shanahan presented a speech about Australian policy in the region we’ve largely heard many times before. One has the sense that Australian policy, at least in its public variant, hasn’t come to terms with the epochal changes afoot in the region. The content of the remarks evinced the victory of wishful thinking over hard strategic reality.

Shangri-La is a vast exercise in public diplomacy and as such an invaluable opportunity to take the region’s strategic temperature. With the US not using the opportunity to dial up the pressure on China, the region’s short-term future looks slightly more stable. The Washington–Beijing trade war hasn’t yet been matched with equivalent military pressure.

But viewed over the longer term, what was on display in Shangri-La’s Island Ballroom was deeply disturbing. It’s clear that China and the US have irreconcilable views of the region and their respective places in it. Neither appears able to recognise that fact or to take steps to compromise and find space for the other. For so long as that prevails, the region’s future will be increasingly bleak.