The ‘2+2’ India–US dialogue and the maritime tango in the Indo-Pacific

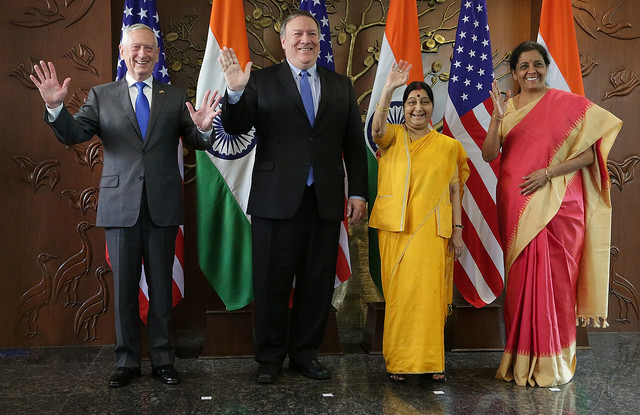

After two deferments and much scepticism, the maiden 2+2 meeting between India and the US was finally held in New Delhi last month. Elevating the erstwhile ‘strategic dialogue’, which involved the Indian foreign minister and the US secretary of state, the revised format included the Indian defence minister and the US secretary of defence as well, giving it the ‘2+2’ moniker. The dialogue yielded significant and tangible outcomes that could potentially have a major impact on maritime security in the Indo-Pacific region.

Arguably the most important event was the signing of the Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA). This is expected to ‘facilitate access to advanced defence systems and enable India to optimally utilise its existing US-origin platforms’.

The signing was received with the usual polarised reactions in India. While some heralded it as the next natural step in India–US relations, others excoriated the Indian government for forsaking the country’s ‘strategic autonomy’, claiming it made India a virtual vassal state of the US. However, since the text of the agreement hasn’t been made available to the public, subscribing to either opinion would be premature, and possibly misguided, at this stage.

Together with the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement signed exactly two years ago, COMCASA promises to change the way the Indian and US navies exercise with each other and with other navies, such as those of Japan and Australia. Indian naval ships, aircraft and submarines could now be part of a common, secure communication grid, instead of makeshift ad hoc arrangements that have thus far been the norm, especially before scheduled exercises. This could potentially augment maritime domain awareness, which is always a challenge for naval forces.

However, it’s at best an operational enhancement and convenience and by itself has no effect, strategic or otherwise, on security in the Indian Ocean or Indo-Pacific region. A lot more needs to be done to achieve favourable effects in the maritime domain, the least of which is to view this and other arrangements as a means and not an end.

The future trajectory of cooperative maritime security engagement in the Indo-Pacific depends to a large extent on the choices India makes, faced as it is today with some tough options. India’s economy needs energy supplies from Iran, its armed forces need the supply of strategic defence systems from Russia, and the world’s largest unresolved land border, which it shares with China, needs peace.

All these could be at stake as India increases security cooperation with the US, especially in the maritime Indo-Pacific. While so far India’s been able to adroitly balance these conflicting imperatives, it’s possible that it may have to make a ‘zero-sum’ choice in the near future—something that it may be ill-prepared for.

As India has deepened its strategic engagement with the US, there’s been a somewhat specious lament on the loss of its ‘strategic autonomy’. That line conflates ‘strategic autonomy’ with ‘non-alignment’, which was the cornerstone of India’s foreign policy during the Cold War. It can be argued that real autonomy would lie in the ability of the country to make choices without duress. Therefore, India should be able to choose to ally or align with other countries if its interests are best served by those choices. Threats to maritime good order in the Indian Ocean and the larger Indo-Pacific region may be pushing India towards a decisive point in this context.

India’s unwillingness to upscale the level of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with the US, Japan and Australia indicates that it either doesn’t see much value in the ‘Quad’ or is reluctant to be part of a perceived anti-China grouping, or possibly a combination of the two. Such reservations mightn’t be entirely unfounded, because it will be hard for four significant yet geographically peripheral powers in the Indo-Pacific to legitimise their actions in response to China’s coercive South China Sea activities or its ‘debt-trap’ diplomacy. The centrality of ASEAN in such a counter would not only be desirable, but indeed essential.

Naval exercises have a great deal of value, but the ‘Malabar’ series of exercises between the Indian and US navies could possibly be approaching the point of diminishing returns, or may have even rounded it. What India will need to establish is the tipping point at which it would be willing to operate with the US, say in an operation to prosecute a Chinese naval unit that poses a threat to Indian interests in the South China Sea. The first step would be to establish whether this is even a possibility. If it isn’t, then the value of such agreements would be limited only to exercises, and they might not offer any significant strategic benefits.

Another important outcome of the 2+2 dialogue is the possibility, albeit somewhat remote, that India may escape US sanctions for continuing to deal with Iran and Russia. The number of exceptions that the US has made for India in the past decade or so, ostensibly to advance this strategic partnership, is significant. Obviously, the US would want something in return.

The question is whether India would be willing, when the time comes, to shed its traditional inhibitions and make the tough calls.