Australia in ASEAN: Indonesian centrality

The roller-coaster nature of Australia’s history with Indonesia—high moments of great optimism, low periods of clash and argument—means that Indonesia’s foreign policy elite is cautious when contemplating the idea of Australia joining ASEAN. But it’s something that Australia’s policy elite might well contemplate.

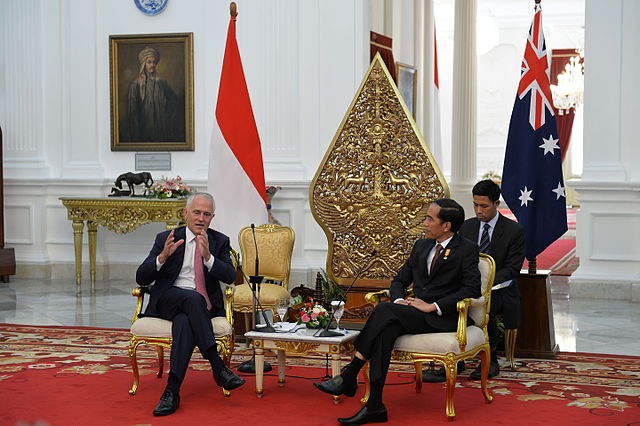

As one example of Australia’s thinking about Indonesia, note Tony Abbott’s view that it’s ‘in many respects our most important overall relationship’. Heading off to Jakarta on his first overseas trip as PM in 2013, Abbott saw the approach to Indonesia as vital: ‘It’s probably not realistic to think of Australia having the same relationship as it has with New Zealand but that’s the direction you would like it to move in.’

The Oz–Kiwi relationship has a depth of history and culture that we’ll never have with Indonesia. But Abbott is surely right that Indonesia is a central factor in Australia’s regional future. I could offer quotes of a similar tenor from every Australian PM going back to Menzies (although the Menzies embrace of the idea of living with Indonesia forever was deeply coloured by dread).

As another example, see Paul Keating’s 2012 Murdoch lecture, in which he argued that Indonesia will become Australia’s most important strategic partner:

How things go in the Indonesian archipelago, in many respects, so go we. Indonesia remains the place where Australia’s strategic bread is buttered. No country is more important to us—and it is a country which has shown enormous tolerance and goodwill towards us. Focus on this country should be a major imperative driving our foreign policy.

An Australian move to join ASEAN would be about the centrality of Southeast Asia to our strategic and economic future. And at the heart of that equation is Indonesia.

A discussion of Australia joining ASEAN is also a way to conceptualise a deeper association with Indonesia. The importance of Indonesia should feed into the understanding of what Australia could do with ASEAN. The bilateral builds towards the regional, just as the regional fosters the bilateral.

The previous Indonesian foreign minister, Marty Natalegawa (2009–2014), rejects Keating’s call for Australia to join ASEAN, arguing that it’d be a distraction for ASEAN and could even inflame tensions inside Australia about our alignment with Asia. Natalegawa’s two big worries are China tearing apart ASEAN and the Jokowi administration musing about a ‘post-ASEAN’ diplomacy.

In both areas, Canberra should argue that a bigger Australian role in ASEAN would be more of an asset than a hindrance. Australia joining ASEAN would help, not hurt, the middle-power game with China.

Natalegawa’s predecessor as foreign minister, Hasan Wirajuda (2001–2009), took a more technocratic approach when I spoke to him about Australia joining ASEAN. Wirajuda pointed to the formal veto—not being part of Southeast Asia —plus an informal rule that a member of ASEAN can’t be part of another regional grouping, as Australia is in the Pacific Islands Forum.

The response to those points is that Australia, as a nation on its own continent, has a series of regions. And formal rules can be changed as circumstances change.

In discussing the Australia-into-ASEAN idea, Wirajuda says he sees it as a replay of the debate within ASEAN about admitting Australia (and New Zealand) to the East Asia Summit: ‘I communicated with my counterparts, early on, especially when Australia was invited to joined the EAS, and said, accelerate the process of integration of Australia into this region, first into ASEAN but then into a larger community-building process.’

Wirajuda says the integration argument succeeded in the EAS, but failed when he was pushing for Australia to be admitted to the Chiang Mai Initiative, the currency swap arrangement between ASEAN, China, Japan and South Korea. He’d strongly supported Australia joining Chiang Mai, but China was even more emphatic in rejecting Australian membership.

Wirajuda’s advice on Australia’s way ahead with ASEAN: ‘I think Australia should make itself more accepted by the region. Speed up your integration—less in a formal process—more in substance.’ He thinks that integration could lead to the moment when ASEAN admits Australia, initially as a half-member with observer status—shifting Australia from the status it has had since 1974 as an ASEAN dialogue partner.

‘I think in the future we should be open, ASEAN should be open to create this special status of observer’, Wirajuda says. ‘So far we work under the ASEAN-plus-one dialogue process, we have a regular dialogue process with Australia. In effect, it would not be much different with observer status, as the ASEAN-plus-one dialogue is done back-to-back with the summit. To me, the margin of difference between dialogue partner and observer is not so much.’

I asked Wirajuda whether reaching for Australian ASEAN membership would be seen as too ambitious, raising too many questions for ASEAN. Ever the diplomat, Wirajuda replied with a meditation on whether Australia would be able to play by the club rules: ‘In the dialogue process, ASEAN-plus-one, our partners can raise anything. But, of course, our partners know how the consensus decision-making process works in ASEAN, which also is perhaps a handicap for our partners.’

Australia’s shift towards ASEAN could happen in step with the broadening and deepening of what Australia seeks to do with Indonesia. That is the perspective of a former head of Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kishore Mahbubani. Here he is making the yes case for Australia’s ASEAN membership. And here are Mahbubani’s further thoughts on how Australia’s embrace of its strategic and economic future in Southeast Asia would move in step with its central relationship, with Indonesia:

Your relations with Indonesia have got to change. You have to show much greater sensitivity to them, closeness to them. Right now you have a good formal relationship, but it’s all about government-to-government, not a heart-to-heart relationship with Indonesia. Mind you, I don’t expect a big-bang change. I think it will be gradual for Australia.

Australia’s gradual movement towards Indonesia must be closer and deeper, just as it must be with ASEAN.