US budget FY2018: F-35 and Super Hornet updates

As long-term readers will know, we keep a watching brief on American aircraft development and production programs that are relevant to Australia. The two most significant ones are the RAAF’s current and future first line strike fighters—the F/A-18 Super Hornet and F-35A Joint Strike Fighter respectively. The Pentagon budget requests for Fiscal Year 2018 have just been released, so it’s time to update our figures.

Previous analyses of the F-35 program are here: FY2014, FY2015, FY2016, FY2017 for the A model (which Australia is buying) and here for a look at the other variants. Our most recent look at the Super Hornet program is here.

The big news about the F-35 program is that there’s no big news—things seem to be on track and delivery is ramping up as costs are coming down. While it might make for a less than compelling blog piece, it’s good news for both the American forces and for the aircraft’s international customers.

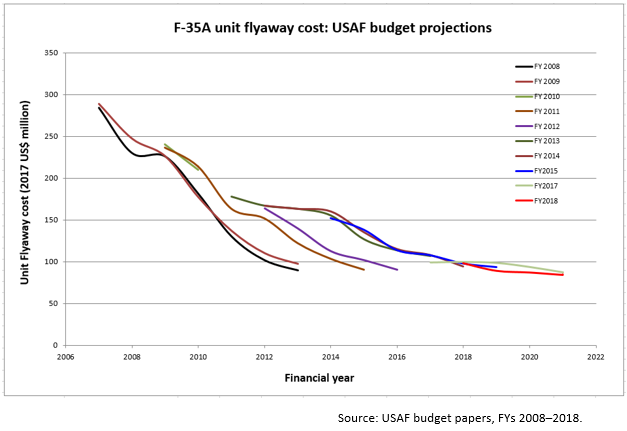

Here are the figures. The red line in the chart below is the latest budget projection for cost, in constant 2017 dollars. It looks like the F-35A unit flyaway cost is levelling out at a figure a little under US$85 million. That’s about what was predicted in the FY2008 budget request, but it’s fair to say that it has been a wild ride between then and now. (And it’s also fair to say that there’s no evidence for any ‘Trump miracle’ in F-35 costs.)

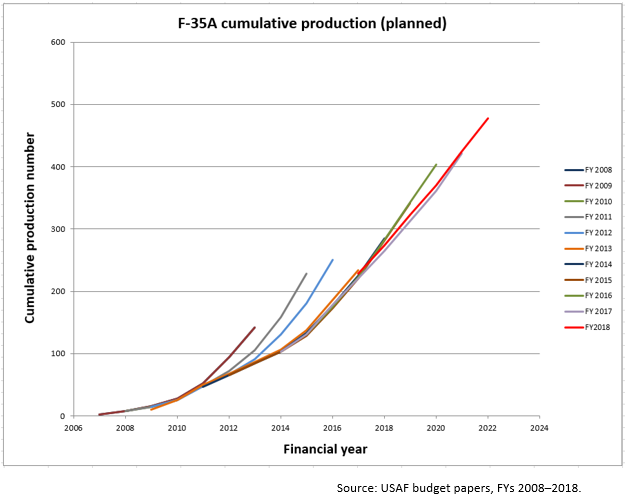

The stability in the future cost figures, which have changed little in the past three budget cycles, suggests confidence that there will be no major interruptions to the remaining development program. Consistent with that, this year’s figures also show a steady ramp up in production rate from this year. On these figures (which don’t include international aircraft), the 500th F-35A will be delivered in 2022.

While all the signs are good for the delivery of Australia’s aircraft in the period 2018–2023, ‘never say never’ is good advice when talking about even the final stages of development of complex equipment. As we’ve argued before, the Super Hornet is Australia’s obvious fall-back position should anything go wrong, and the story there is encouraging as well.

While all the signs are good for the delivery of Australia’s aircraft in the period 2018–2023, ‘never say never’ is good advice when talking about even the final stages of development of complex equipment. As we’ve argued before, the Super Hornet is Australia’s obvious fall-back position should anything go wrong, and the story there is encouraging as well.

In fact, the Super Hornet is having something of an “Indian summer”. President Trump has been a frequent advocate of the naval fighter, famously tweeting in December that he was considering the platform as an alternative to the F-35. Since then, Boeing has been on the offensive, most recently proposing an even more capable Block III Super Hornet as an alternative to the F-35C.

There’s no approved program to develop the Block III, but Block II Super Hornet production is ramping up again. In March, the President proposed that the Pentagon fund an additional 24 Super Hornets in the present fiscal year (FY2017), which ends in September. Those 24 Super Hornets are present in the USN’s FY2018 budget for aircraft procurement [PDF, p.71]. While they didn’t agree to bankroll the full 24, the US Congress approved 14 additional aircraft in the final FY2017 budget.

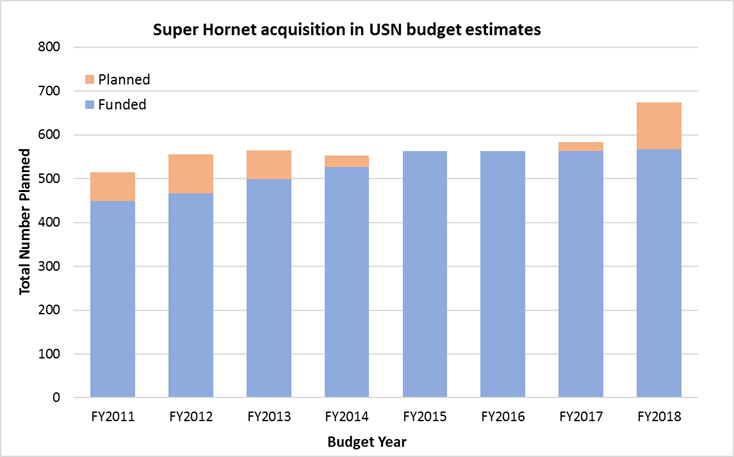

The final chart below shows changes to Super Hornet acquisition plans, based on annual USN budget proposals. The number of aircraft was increased every year in the early 2010s, then capped at 563 aircraft in 2015/2016, before the recent additional bump.

The FY2018 budget estimates include projections for an additional 66 Super Hornets between FY2019 and FY2022 that weren’t present in last year’s budget estimates. That’s good news for anyone else considering buying Super Hornets (Kuwait, Canada), since it keeps the production line active and costs stable. And it’s good news for those of us who think that a further Super Hornet purchase is the best Plan B in the (increasingly unlikely) event of a major setback to the F-35 program.

It would be a mistake to interpret this as a move away from the carrier variant F-35C, even though production of the latter is slightly slowed in the new budget (about 6 fewer total aircraft by FY2021). It’s more likely about the USN’s strike fighter readiness crisis, as new-build Super Hornets are the most ‘ready to go’ option for the USN. That’s consistent with Defence Secretary Mattis’ comments that he wants to prioritise readiness over modernisation or expansion.

About two thirds of the USN’s strike fighters are currently unavailable at any given time due to required maintenance or insufficient spare parts. That’s partially due to earlier delays in the F-35 program, and partially due to underfunded recent sustainment budgets. Buying new aircraft will help take some of strain off the system. And it leaves open the USN with the option of ramping up Super Hornet production or shifting to Block III later.