Staffan de Mistura: a ‘chronic optimist’ takes on Syria (part 2)

UN Special Envoy for Syria Staffan de Mistura’s background and leadership style (see part 1) have influenced his approach to the Syrian conflict from the day UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon asked him to take on the role. When he got the call in July 2014, de Mistura was enjoying a lovely semi-retirement on the isle of Capri after promising his fiancée and two daughters (from a previous marriage) a ‘more normal life’ after nearly four decades of bouncing between war zones. De Mistura was inclined to say no, but as he tried to sleep that night, he felt guilty. Ban’s words about the numbers of civilians killed and the refugees echoed in his head. He called the Secretary-General back at 3am and accepted the job.

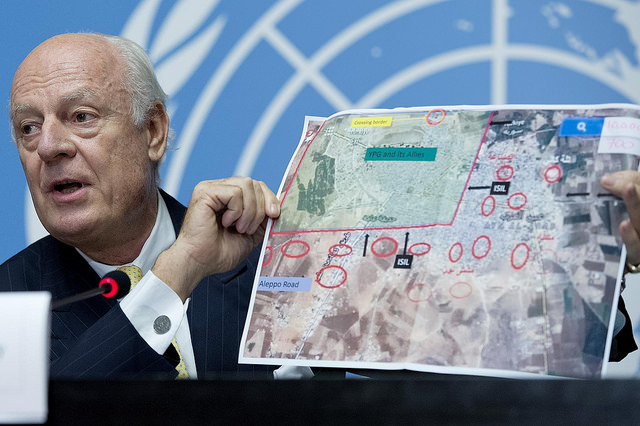

De Mistura initially tried a more bottom-up approach to peacemaking than his predecessors. He took an immediate risk in late 2014 when he proposed a series of ‘freeze zones’ or small, local freezes of violence in the iconic Syrian city of Aleppo. The theory was that the neighbourhood-level freezes could later be linked together and eventually replicated in other cities. While the envoy’s advisors suggested that de Mistura pick a less difficult place, he felt strongly that Aleppo would have symbolic power in demonstrating ‘drops of hope’ and the need to protect civilians elsewhere. De Mistura also hoped that drawing public attention to Aleppo, which was close to collapse, might help prevent the regime or the opposition from escalating the fight.

When both the regime and the opposition ultimately eschewed the Aleppo initiative, Ban instructed de Mistura to try to organise political talks, shifting the envoy back to a more top-down approach to conflict resolution. De Mistura has tried to be more inclusive, acknowledging that the conflict is part of a larger regional contest and shifting geopolitical dynamics. To lay the groundwork for the current talks, he first held one-on-one consultations in Geneva with hundreds of leaders, groups and factions. Shortly thereafter, he logged over 25,000 miles of air travel in two weeks to meet with officials in Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and China.

De Mistura’s forward-leaning style, however, has at times landed him in hot water. The envoy’s critics note that he can sometimes speak too soon and too much, resulting in hyperbole and diplomatic missteps. He offhandedly told reporters in early 2015 that Assad should be part of the solution, sparking intense criticism as it came the same day that the Syrian Government launched missiles and barrel bombs in the city of Douma. De Mistura insists he meant that Assad should be part of the solution for setting up the Aleppo freeze, not part of the solution to the overall Syrian conflict, but his comments further alienated the opposition. De Mistura’s former political director claims that the envoy has at times lost credibility because he tends to tell his interlocutors what they want to hear, and think about the consequences later.

In his efforts to innovate where the status quo has failed, Mistura has relied heavily on small changes in terminology in an attempt to generate big results. He has tried to distinguish the current talks from the high-level summits of his predecessors by calling them the ‘Geneva Intra-Syria talks’ not ‘Geneva III’. His initial Aleppo plan was about ‘freeze zones’ not ‘ceasefires’, which had failed in the past. He referred to his consultations in Geneva as a ‘stress test’, not ‘negotiations’, and he prefers to speak of ‘action plans’, rather than ‘peace plans’. While those terminological nuances might make sense in theory, the media’s disregard for them seems to render his effort ineffective.

As could be expected, de Mistura has come under fire from all sides. The opposition has accused him of favouring the regime, and he has angered the regime with critical public remarks on airstrikes. Political commentators have criticised him for failing to engage the opposition enough, falling victim to manipulation by the regime, and focusing on the political process at the expense of reducing violence against civilians. De Mistura’s own former political director resigned in anger, accusing the envoy of cronyism and incompetence. However, one doesn’t spend 40 years in the UN without developing a thick skin. De Mistura acted quickly to hire a new political director who specialises in constitutional law, and he redoubled his efforts to smooth over relations with opposition leaders. For the most part, he seems undeterred by his critics, saying that complaints are inevitable.

Looking ahead to when the proximity talks resume on 7 March, de Mistura’s efforts may very well continue to sputter or stir up controversy, but it’s hard to blame him for trying and there are still benefits to continuing the conversation. UN expert Richard Gowan explains that maintaining a negotiation process for the sake of it is sometimes an unglamorous necessity. Demonstrating both the value and the risk of talks, he says,

‘UN mediators have kept talks over other intractable conflicts, ranging from Cyprus to Somalia, going for years or decades. It is sometimes necessary to hold consultations to remind everyone that a diplomatic track is still available, although there is a risk that sustaining the process becomes an end in itself.’

Peace and conflict expert Jeni Whalan argues that we mustn’t give up on the Syria talks, highlighting additional advantages:

‘Inconclusive mediation now can still lay essential foundations for a concrete settlement later. Talks allow warring parties to gather new information, reconsider their views of the enemy, and identify potential areas of common ground that can’t be gleaned from battlefield tactics.’

De Mistura himself acknowledges that the talks will be an uphill battle but believes that ‘the time has come to at least try hard to produce an outcome’. In the face of one of the most complex and intractable conflicts of our time, it’s anyone’s guess as to how long his ‘chronic optimism’ will last.