Funding defence and squaring the circle

On Tuesday, the Defence Minister re-committed to releasing a White Paper in the first quarter of this year. That means it’ll be fewer than 51 sleeps before we see the document. More importantly, it means that the White Paper will be sent to the printer before the 2016 federal budget is locked down.

In times past, the resulting sequence of events wouldn’t be a problem. But the forthcoming White Paper comes with big expectations inherited from the Abbott government; specifically, the promises of a costed affordable plan and for defence spending to reach 2% of GDP within a decade. Committing to specific spending levels, let alone a timetable to reach 2% of GDP, is easier said than done with the overall budget still a work in progress.

And it’s not like Turnbull government is in honeymoon mode. The May budget will be the last opportunity for Scott Morrison to establish the government’s economic credibility prior to the election, and the political trainwreck following Joe Hockey’s 2014 budget shows how much is at stake.

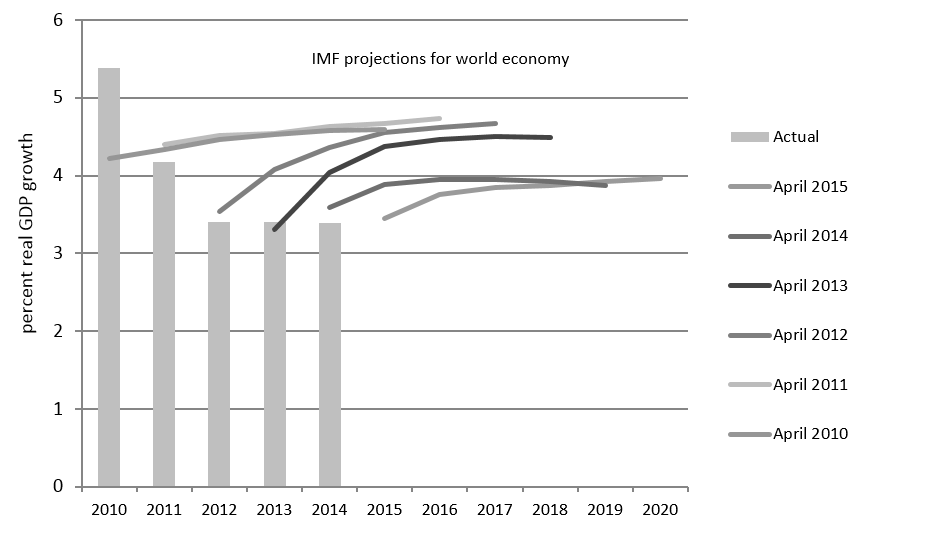

To complicate matters further, the economic and fiscal situation has moved into uncharted waters—not just for Australia but also internationally. Consider the graph above of successive estimates of global growth made by the International Monetary Fund from 2010 onwards. In each and every year, growth has fallen well a below expectation (which means that 2% of GDP ain’t what it used to be). Economists are flummoxed to explain the persistent stagnation. Central bankers continue to search for ways to promote growth with interest rates close to zero and, in some cases, negative. Faith in unconventional monetary policies such as ‘quantitative easing’ is evaporating. Commodity prices have collapsed and equity markets are worryingly volatile.

As a commodity exporting nation with a high dependence on company tax to balance the books, the government’s fiscal situation continues to deteriorate. Wayne Swan said we would be in surplus by 2012–13. Joe Hocky started out with a goal of 2015–16. In December, Scott Morrison pushed out the expected return to surplus to around 2020. But even that dismal projection presumes, somewhat optimistically, that measures currently stalled in the Senate will be passed. Worse still, it’s predicated on continuing unmitigated bracket creep.

Meanwhile, as deficits pile up, so too does Australia’s net debt. While net debt is only projected to grow to around 18% of GDP—a mere third of a trillion dollars—towards the end of the current decade, there’s no reason for complacency (as Treasury Secretary, John Fraser, made clear in a recent speech). Australia’s ability to manage economic risks depends upon maintaining a good credit rating so we can borrow money at favourable rates. Mounting debt works in opposition to this.

Readers of The Strategist don’t need to be reminded that the strategic environment is no more favourable than the economic. These are challenging times, wherever you look. How then will the Turnbull government balance its investments to mitigate economic verses strategic risks? Make no mistake; it’s a zero-sum game. Ignore the snake oil about defence innovation and spinoffs: every dollar spent on defence is a dollar that can’t be used to retire debt.

In the short to medium term, I suspect that the government has limited flexibility about defence spending. In contrast to the lead up to previous White Papers, acquisition approvals have continued apace over the past two years. In theory, some of the unnecessarily rushed shipbuilding activity planned for later this decade could be slowed down, but that would come at a political cost from the frenzied state of entitlement that calls itself South Australia.

Thus, the good news for Defence is that the forthcoming White Paper is likely to confirm extant expectations about the ongoing modernisation and expansion of the defence force. Just as importantly, they will likely provide adequate funding for the task at least until the end of the decade (unless we see a repeat of the regrettable period 2009 to 2013 when Defence was asked to square the circle of ambitious plans and parsimonious budgets).

One thing the government could do is jettison the 2% of GDP target. Setting aside the myriad of technical reasons why a GDP target is dumb (see here and Chapter 3 here), doing so would provide some flexibility in the years ahead to calibrate defence spending in light of evolving strategic and economic imperatives. In the good times of the resource boom, we could afford Defence’s planners the luxury of long-term funding certainty (and they returned the favour by handing money back unspent). Those days are over. Australia’s overall best interests are today served by a government that’s agile and adaptive in its allocation of resources.