Fair warning: Australia’s terrorism advisories

Last September the terrorism advisory was raised by Prime Minister Tony Abbott from medium to high. We’d been stuck at a medium level alert for thirteen years.

The Australian government communicates with the public in many ways about terrorism threats. But the question is, does our formal terrorism public alert system make a significant contribution to our counterterrorism measures? Does it generate confidence in the public, the states and territories, local government and industry to undertake what might prove to be costly protective measures?

No formal terrorism alert system can deliver perfect security or tell us exactly what we should look for—intelligence is almost never that precise. We’re seeing the rise of so-called ‘lone wolf’ terrorism attacks. As the Prime Minister has noted, all that’s required for a domestic Islamic State-ordered terror attack is a ‘knife, iPhone and a victim’. It’s these kinds of lone actor attacks that have raised public doubts about the utility of a general, all-purpose public terrorism advisory system.

But in an ASPI paper released today we argue that despite its limitations, such a system can be useful in increasing the awareness of the community about terrorism risks, and be helpful to our security and law enforcement agencies in asking for public assistance: it widens the set of eyes and ears for our national security community. Terrorism advisories can provide critical infrastructure operators with guidelines as to what a heightened threat means for their industries and how this might best guide their operations.

We suggest several ways to make our terrorism warning system better meet the public’s expectation that the government will provide useful information on terrorist threats and advice about required changes to behaviour.

We would endorse the findings of the recent Commonwealth Review of Australia’s Counter-Terrorism Machinery that there is confusion between the threat level, (classified by ASIO), and the public alert system, where changes are announced by the Prime Minister.

It would be sensible to collapse the two systems into one public alert system, which is decided and publicly announced by the Director-General of ASIO, and which can be accompanied by an unclassified narrative. The DG of ASIO would be the national terrorism ‘barometer’ on terrorism alerts and they’d call the shots. This would help depoliticise the current warning system.

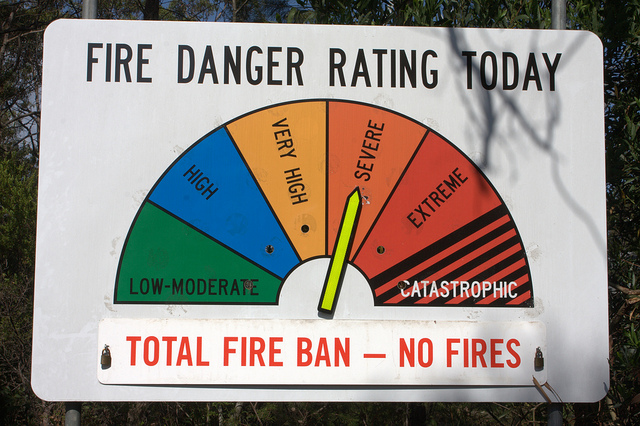

There’s now an inherent difficulty in lowering the terror alert. Unlike weather or fire alert levels, there’s no scientific data indicating when a terrorism threat has reached its peak and then passes. But a sunset clause, where there’s a mandatory expiration of a raised terrorism level after six months, would allow the level to be lowered objectively.

It would provide a sufficient amount of time for intelligence and law enforcement agencies to assess a situation. This would lessen the risk that an elevated level just becomes the ‘new normal’: there’s a degree of community expectation that at some point the level could go down. The mandatory lowering of an alert after a certain period of time—unless there’s evidence that it shouldn’t be changed—would reduce the higher costs associated with remaining on elevated alert levels, such as those incurred by critical infrastructure operators or the police, who may be required to provide extra resources for special events.

A generic national alert level system isn’t appropriate to a country as geographically large as Australia. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade provides public information on risks in different countries where Australians might travel, and the public is familiar with that system.

Such an approach might be adapted for our terrorism warning system by making it more geographically discerning. This would strengthen our warning system as an effective tool for communicating useful information to the public. It would help tap information from the public to prevent terrorist attacks.

If the alert language is too ambiguous, that’ll just reduce the utility of any advisory system. It would be prudent to test the narratives at each level with the public to see how useful the community finds them, especially what the system suggests people to do at each level. The NSW Premier’s Department Behavioural Insights Unit is one body that might undertake this work.

Finally, a public awareness campaign communicating any changes to our terrorism advisories would be helpful. This should include social media in the form of an Australian government national security Facebook page and a Twitter account to keep Australians updated about information on terrorism warnings.