China’s decision making: interpreting the ADIZ

The puzzle that is the Chinese policy making process has been taunting analysts over the last few weeks. First, a handful of Strategist posts (here, here and here) discussed whether incidents involving China’s maritime law enforcement authorities in Indonesia’s EEZ signify that China is contesting waters it deems to be its own. And now a disagreement has arisen over the interpretation of China’s imposition of an Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) over much of the East China Sea. Harry White argues that this action should be seen as a deliberate signal of China’s willingness to defend its interests, while David McDonough suggests that the action may have been driven by subnational political actors (the PLA) without the Chinese leadership fully appreciating the move.

The puzzle that is the Chinese policy making process has been taunting analysts over the last few weeks. First, a handful of Strategist posts (here, here and here) discussed whether incidents involving China’s maritime law enforcement authorities in Indonesia’s EEZ signify that China is contesting waters it deems to be its own. And now a disagreement has arisen over the interpretation of China’s imposition of an Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) over much of the East China Sea. Harry White argues that this action should be seen as a deliberate signal of China’s willingness to defend its interests, while David McDonough suggests that the action may have been driven by subnational political actors (the PLA) without the Chinese leadership fully appreciating the move.

It’s important to be careful when interpreting the relationship between actions and state intentions because individual actions, like China’s ADIZ declaration, can be seen to have bearing on the fundamental questions of global politics. For example, it caused Ben Schreer to question the possibility of China’s peaceful rise. In their clinical dissection of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Essence of Decision, Graham Allison and Phillip Zelikow present three models for understanding state actions, each emphasising the role of different actors and dynamics of interaction.

The first is the ‘rational actor model’, in which a unitary state interacts with the international environment in goal-seeking behaviour. The second model focuses attention on what various state organisations can and cannot do in a given situation, revealing the role internal organisational factors play in shaping state actions. This ‘organisational output model’ shows how when a government sets an organisation a task like, say, ‘protect fisheries resources within operational zone X’, they are essentially pushing a button, setting in motion processes over which they may then have limited control. The third, ‘bureaucratic politics model’ notes that the leaders who sit atop organisations, such as departmental and service chiefs, are players in a competitive and hierarchical political process. They act in accordance with competing definitions of the national interest, as well as organisational and personal interests. They are also receptive to political pressures like popular nationalism.

Not all actions by subnational organisations fully reflect the foreign policy priorities of that state’s leadership, so it is wrong to infer a fundamental geostrategic intention in every individual act. The PLAN’s use of fire control radar against a Japanese ship in February this year appears to be indicative of problematic civil-military relations, exacerbated by the inevitable autonomy of naval commanders at sea. It is out of an appreciation of such operational realities that countries set up crisis hotlines and establish operational protocols.

Conversely, subnational organisations are sometimes deliberately used as tools to further the achievement of national objectives. This is clearly the case with China’s use of Maritime Law Authorities (MLA’s) and its territorial disputes in the East and South China Seas. Under cover of plausible affronts on its territorial claims, China has opportunistically deployed MLA’s to enhance its effective control over disputed areas, or vitiate the effective control of others. Exercising effective control of an area strengthens a state’s legal claim to sovereignty, giving individual incidents in disputed areas significance beyond their immediate impact. Because these incidents in China’s periphery are so widespread, and occur in tandem with forms of diplomatic and economic pressure, observers have little reason to doubt the purpose of these individual acts. Where these incidents aren’t accompanied by parallel efforts to apply diplomatic pressure or prevent resource exploitation, as in the Indonesian EEZ near the Natuna Islands, the significance of these incidents is less certain.

China’s sudden declaration of the ADIZ wasn’t an opportunistic response to any Japanese action. According to reports, the ADIZ was approved by Xi Jinping four months ago, and had been proposed by the PLA even earlier than that. While analysts have argued that the main objective of the ADIZ is strengthening China’s legal claim to the disputed islands, this conclusion is extrapolated from China’s actions using rational actor assumptions. It isn’t grounded in insights into how Chinese policy actors themselves viewed this action. Without a fuller picture of the Chinese policy process we may never be sure of how to interpret China’s ADIZ. Was it a deliberate attempt to change operational realities in the disputed area, in which case China blinked when challenged? Or does China’s lack of response to encroachments in the ADIZ suggest that it was intended more as a legal fiction than a military reality?

This uncertainty points to a real problem. In the absence of illumination of China’s politico-military decision-making, China’s neighbours will assume the worst about what its actions say about China’s national objectives. The secrecy which maintains the façade of party unity and control at the domestic level costs China in international trust. Unless China shows greater openness in its pursuit of its (legitimate) national interests, it will surrender the international media narrative to unsympathetic interpretations. This should be seen in Beijing as a threat to China’s peaceful rise.

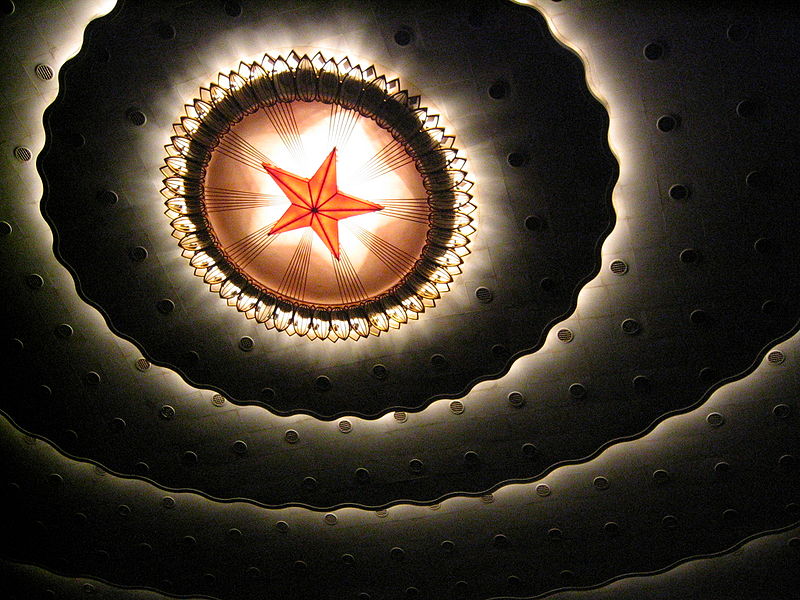

Daniel Grant is the 2013 Robert O’Neill Scholar at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at the Australian National University. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.