China’s new map: just another dash?

China’s new national map re-affirms its historical South China Sea claims and incorporates a tenth ‘dash line’ off Taiwan. It has created a few ripples in Southeast Asia and beyond. Since the tenth dash itself isn’t new, there’s less novelty to this development than first meets the eye. But it raises important questions about China’s intentions, due to the basic ambiguity of its position.

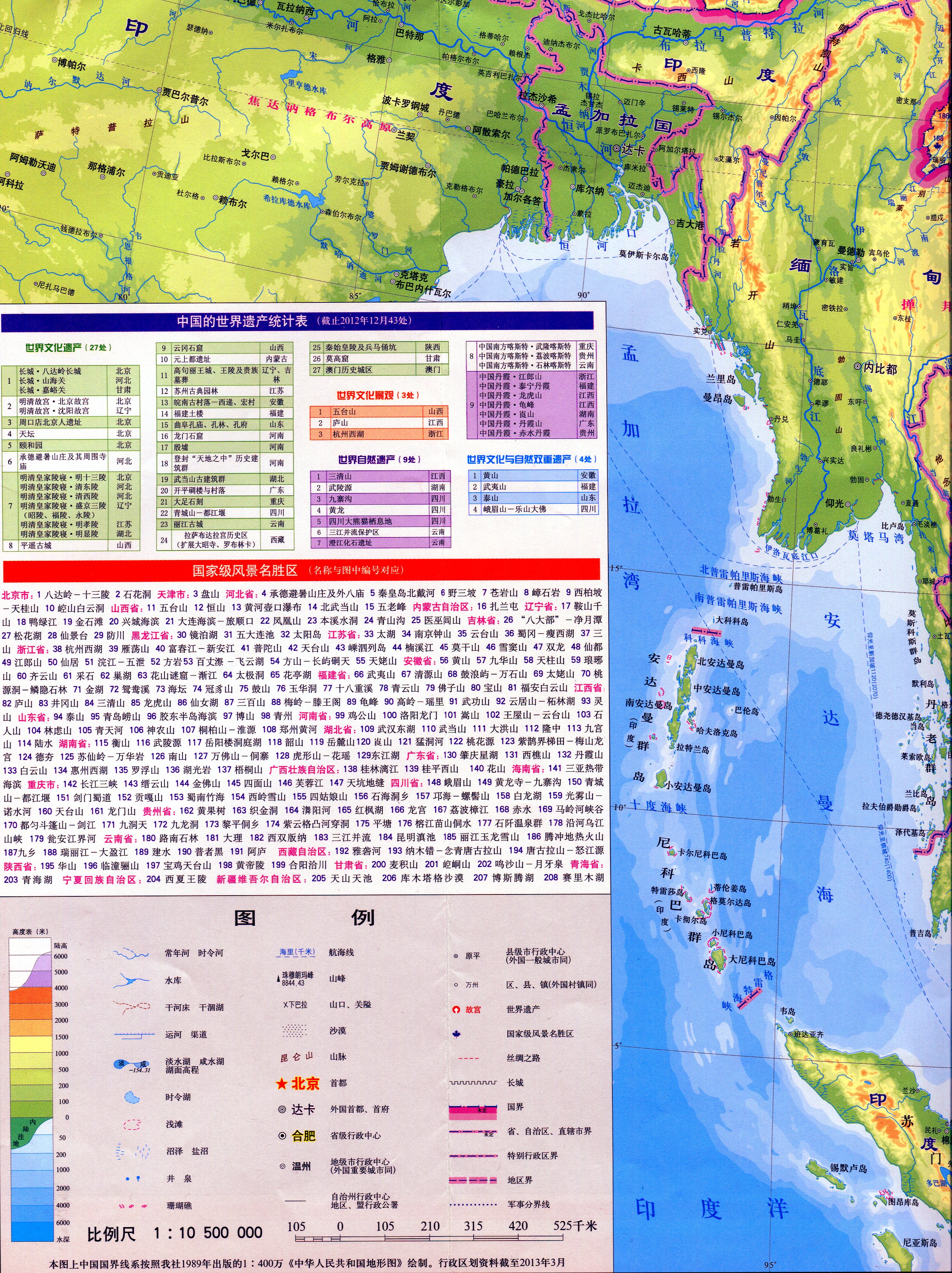

The latest national map of China was published earlier this year by SinoMaps Press, under the jurisdiction of the State Bureau of Surveying and Mapping. In other words, it’s officially approved. As with past maps, Beijing’s claims in the South China Sea are represented by the familiar nine-dash line, which is duplicated on both sides of the map. Whereas the nine-dash line was previously included as an inset and without the tenth dash line off Taiwan, it’s now fully integrated into the new national map. The 10-dash line map also features as a background in China’s latest passports, which have drawn protests from Vietnam and the Philippines.

Close-ups of the front and back of the new SinoMaps Press map showing China’s ten-dash line in the South China Sea. Courtesy of SinoMaps Press.

Close-ups of the front and back of the new SinoMaps Press map showing China’s ten-dash line in the South China Sea. Courtesy of SinoMaps Press.

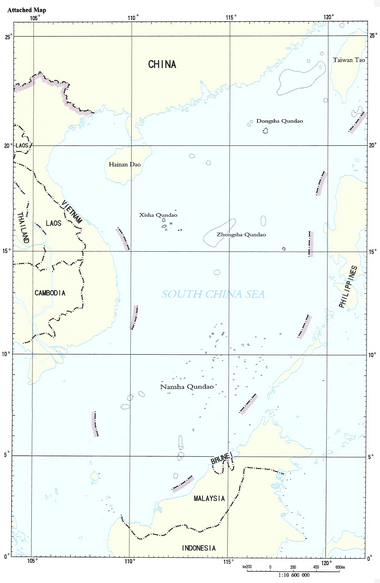

The reappearance of the tenth dash has raised eyebrows in Japan because it’s drawn very close to Yonaguni, Japan’s westernmost island in the Ryukyu chain, only 70 miles from Taiwan. Yonaguni isn’t claimed by China – (unlike the Senkaku/Diaoyu islets lying to the north) but is practically obscured by the shading that emanates from China’s tenth dash. Beijing has previously asserted its South China Sea claims with reference to a nine-dash line ‘inset’ map, which for example was appended to China’s May 2009 official protest against Vietnam and Malaysia’s joint submission to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf.

China’s South China Sea ‘inset’ map showing the previous nine-dash line. Courtesy of SinoMaps Press.

China’s South China Sea ‘inset’ map showing the previous nine-dash line. Courtesy of SinoMaps Press.

So while the tenth dash isn’t new, its re-unification with the other nine dashes in the latest map is politically significant. First, in a cross-strait context, it symbolically subsumes Taiwan’s territorial claims in the South China Sea, derived in parallel from the original Kuomintang claim. Moreover, Taipei still occupies the largest island in the Spratlys, Itu Aba or Taiping Island. Despite the improvement in cross-straits ties in recent years, Taiwan’s political leadership is wary of accepting overt support from China for its maritime claims, which also extend to the Senkaku/Diaoyu in the East China Sea. Beijing sees these maritime territorial claims as mirroring its own. For Beijing, they’re a means to narrow the cross-strait gap further by aligning Taipei and Beijing along a common nationalist axis, capitalising upon Taipei’s own recent tensions with the Philippines and Japan. Beijing’s overtures may in future extend to Taiwan’s scholarly community, with the aim of buttressing the evidential base for China’s historical claims.

The symmetry is even closer in China’s ongoing confrontation with Japan over the Senkaku, since China’s claim to the islands runs through Taiwan. The tenth line on the map therefore hints at a broader linkage in Chinese minds to the East China Sea, where Beijing’s political and strategic priorities are currently centred. It’s also read as such by Japanese analysts.

Legend of China’s new map. Courtesy of SinoMaps Press.

The new map has attracted attention further south, given that the legend denotes the dash line as a ‘national boundary’ (国界), using identical shading to China’s land borders, radiating out from the nine dashed lines within the South China Sea. The shading has the visual effect of projecting China’s claims, however defined, closer to the coastlines of the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam. However, close inspection, reveals that the nine-dashes are all in unchanged locations from previous Chinese maps. China probably wishes to maintain some ambiguity about the status of the dash line, as further suggested in the map legend, where the space in between the dashes is marked (in diminutive characters) as ‘boundary not defined’ (未定).

Southeast Asian reactions to date have been subdued, at least publicly—although the Philippines’ Department of Foreign Affairs apparently sent a confidential note verbale to the Chinese Embassy, protesting against ‘the reference to those dash lines as China’s national boundaries’. Indonesia’s semi-dormant sensitivities in the South China Sea may be pricked by the fact that China’s westernmost dash line clearly bisects Indonesia’s gas-rich Exclusive Economic Zone off Natuna, potentially reviving concerns that Jakarta believed it had put to bed with bilateral reassurances received in the early 1990s. Thus far Indonesia hasn’t offered any official objection to the new map, perhaps preferring to dwell on the positive fact that China’s mapmakers have acknowledged the outer limit of Indonesia’s archipelagic waters to the north of Natuna. Yet China shouldn’t take Indonesia’s neutrality in the South China Sea disputes for granted. In reality, Indonesia’s maritime resource equities are potentially on the line, despite not being a claimant to the Spratlys. Jakarta previously queried the legal basis for China’s nine-dash claim in 2009 through the UN, while Chinese and Indonesian patrol boats faced off in an incident near Natuna in June 2010 (PDF). Equally, the PLA Navy’s late-March 2013 excursion to James Shoal, traditionally regarded as China’s southernmost claimed feature in the South China Sea (even though it is submerged), ruffled feathers in Kuala Lumpur which has traditionally felt less threatened by China’s claims (PDF).

Since maps don’t carry independent legal weight under UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), China’s overriding challenge remains the need to bring its South China Sea claims into conformity with international law. Privately, some Chinese interlocutors are conscious of the incompatibility between China’s UNCLOS obligations and a maximalist interpretation of the nine-dash line as a territorial enclosure. They seek to reassure foreigners that China’s claims extend to islands and other land features within the lines, as well as vaguely defined ‘historical rights’. A recent article for the American Journal of International Law co-authored by Judge Gao Zhiguo, China’s appointee to the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea, opined that the nine-dash line has three meanings:

- ‘it represents the title to the island groups that it encloses’

- ‘it preserves Chinese historic rights in fishing, navigation, and such other marine activities as oil and gas development in the waters and on the continental shelf surrounded by the line’

- ‘it may serve as a basis for ‘potential maritime delimitation lines’.

In such an ambiguous context, official assertions of the dash line will only continue to stoke unease among other South China Sea littoral states and China watchers further afield.

China’s recent announcement that it’s prepared to discuss a Code of Conduct on the South China Sea is welcomed by ASEAN members. But it appears aimed primarily at repairing bridges with the grouping following last year’s divisive denouement at the ASEAN Regional Forum, without committing to hard timetables. Meanwhile, the red-carpet treatment accorded to Vietnam’s President Truong, when he visited Beijing in June, suggests that Beijing is also intent on mending bilateral fences with Hanoi, as the most potentially problematic of China’s rival claimants in the South China Sea. It’s tempting to read into this an ulterior motive of further isolating the Philippines, currently the target of Beijing’s ire for unilaterally launching arbitral proceedings, formally under way as of 16 July, that have quizzed the legal basis for China’s territorial claim (PDF).

Although the disputed islands and rocks in the South China Sea are now receiving unparalleled international judicial scrutiny, China’s mapmakers can probably put away their dividers, safe in the knowledge that Beijing’s new leadership will preserve the ambiguity about the full extent of their South China Sea claims which the dashed line affords.

Euan Graham is a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore. This post is adapted from an article on the RUSI UK Newsbrief and is reprinted here with the kind permission of RUSI UK.