Business or plunder: international corruption robbing Africa’s poor

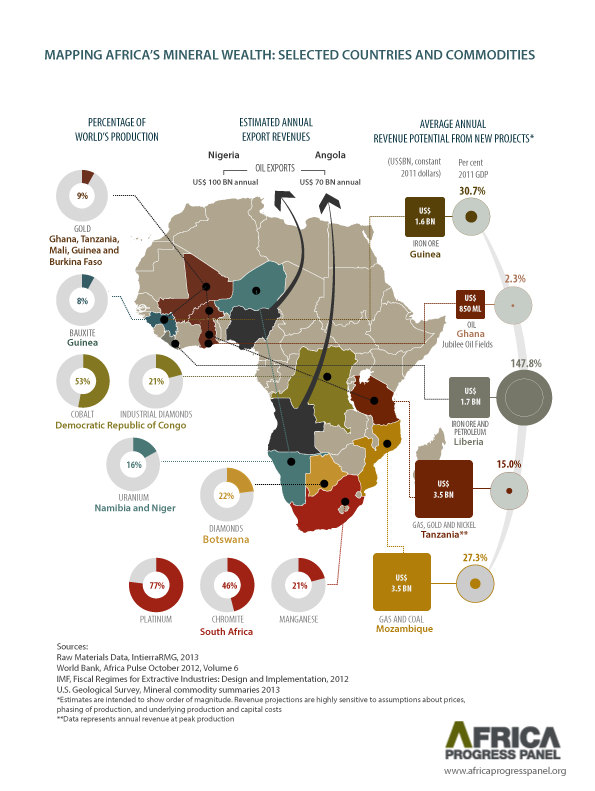

Africa is a resource-rich continent, but most of its people live in extreme poverty. Amid the world’s resources boom and high global demand, Africa’s vast oil, gas and mineral resources have the potential to drastically improve and transform the lives of African populations.

So why do some of the world’s poorest people live in one of the world’s most resource-abundant regions? And, as Australian business, investment and trade with African countries increase, how can this economic injustice simply be ignored?

Global momentum to address the current dismal state of affairs is mounting, and Australia needs to take an active part in efforts to ensure greater transparency and accountability in Africa’s resources sector and international transactions.

The Africa Progress Report is produced by the African Progress Panel and published in May each year. The panel’s composed of influential business and political figures and is chaired by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan. Its mandate is to ‘advocate at the highest levels for equitable and sustainable development in Africa’.

This year’s Africa Progress Report—released at the World Economic Forum meeting in Cape Town—focuses on the extractive industries of oil, gas and mining. The report’s findings made headlines around the world, highlighting exactly why African populations aren’t yet fully benefiting from the continent’s resource wealth. It details the horrifying extent of the corrupt practices that plague Africa’s resource sectors and gives details of secret mining deals, the undervaluation of state assets, tax evasion and transfer pricing (moving profits to jurisdictions with lower tax). It’s estimated that transfer pricing is costing Africa $34 billon each year.

The report uses the mining sector in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) as a key example. It explains that the DRC ‘incurred losses of $1.36 billion between 2010 and 2012 as a result of the alleged undervaluation of state assets in five mining deals’. It states that ‘with some of the world’s richest mineral resources the DRC appears to be losing out because state companies are systematically undervaluing assets. Concessions have been made on terms that appear to generate large profits for foreign investors.’ And this while the Congolese are one of the world’s poorest populations.

Kofi Annan has said that ‘We [Africa] are not getting the revenues we deserve, often because of either corrupt practices, transfer pricing, tax evasion and all sorts of activities that deprive us of our due.’ Annan explained that Africa can’t remedy this loss of revenue alone: ‘the tax evasion, avoidance, secret bank accounts are problems for the world … so we all need to work together, particularly the G8, as they meet next month, to work to ensure we have a multilateral solution to this crisis.’ Annan described the current situation as akin to ‘taking food off the table of the poor’.

The key to battling corrupt practices that rob African populations of their resource wealth is improvements in the level of transparency and accountability in the resources sector and in the operation of international companies. For example, in Liberia and Guinea, mining contracts can now be scrutinised online by the public, in a bid to curb corruption in the sector.

Annan says he’s encouraged by the international multilateral response to the challenge, including legislation in the US (the Dodd–Frank Act) and Europe requiring extractive companies ‘to meet higher levels of disclosure’. He’s also buoyed by the fact that the British have put international cooperation on taxation on the agenda for the G8 summit meeting to be held next month.

A more prosperous Africa for all is a real possibility, and the international community has the most important role in making it a reality. As a responsible global player and with expertise in the extractive industries, Australia can make a valuable contribution to making sure that those who rob from the poor have nowhere to hide.

In Africa, the mining, oil and gas industries produce seven times the amount that the continent receives in donor aid. There’s a real possibility that sovereign wealth funds could be created to meet the needs and aspirations of future generations, using the huge revenues flowing in from resources sales. Perhaps they could take a form similar to the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund (the Government Pension Fund—Global) or be variations on Australia’s Future Fund. Capturing today’s wealth to help meet tomorrow’s national needs in Africa is an opportunity that shouldn’t be missed.

In conclusion, a final quote from the Africa Progress Panel:

Imagine an African continent where leaders use mineral wealth wisely to fund better health, education, energy, and infrastructure. Africa has oil, gas, platinum, diamonds, cobalt, copper, and more. If we use these resources wisely, they will improve the lives of millions of Africans.

Sabrina Joy Smith is a PhD candidate with the Centre for the Study of the Great Lakes region of Africa at the Institute for Development Studies and Management, Belgium. She is currently based in New South Wales. Infographic courtesy of Africa Progress Report 2013.