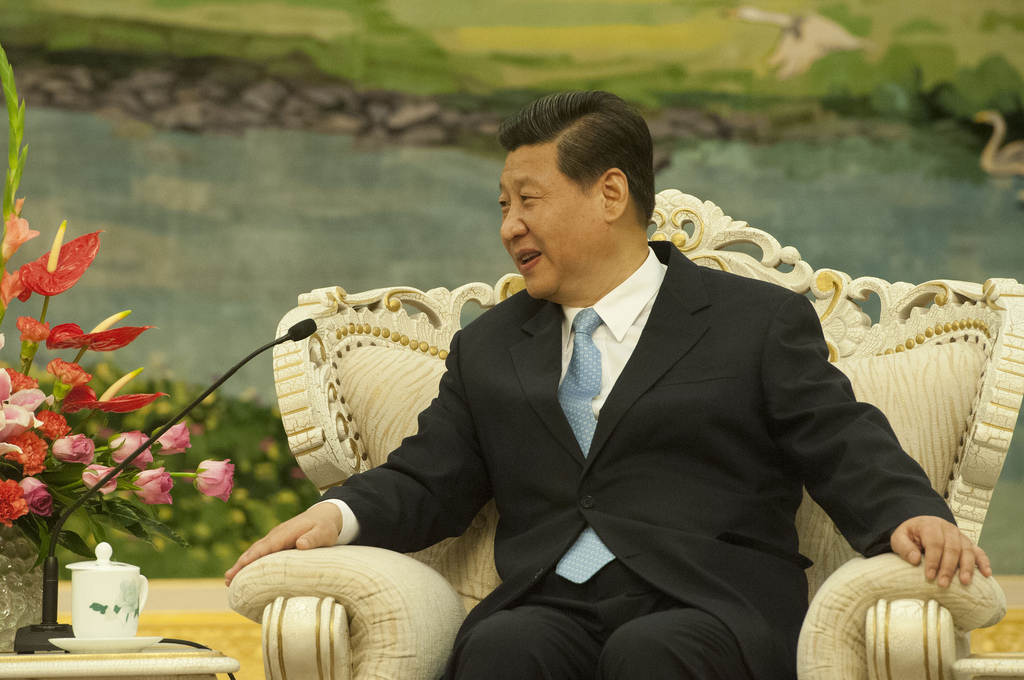

Who is Xi Jinping and what will he mean for Australia?

At the launch of the Australia in the Asian Century White Paper, Lowy Institute Executive Director Michael Fullilove made an interesting observation during question time about the level of attention paid in Australia to developments in the United States versus developments in China. Specifically, he commented that the Australian public is told a lot about the US Presidential candidates—right down to the marathon running time of the Republican candidate for Vice President—but, despite the imminent leadership change in Beijing, we hear very little about the incoming Chinese President.

Perhaps part of the reason for our lack of interest in the Chinese leadership change is because it’s more or less pre-ordained, whereas in the US, Romney and Obama are engaged in a dramatic race to the finish, battling it out in televised debates. (Some prefer to imagine what a heated Chinese leadership debate would like). Yet, the Chinese leadership change is a once-in-a-decade event and, considering we know comparatively little about Xi Jinping, what should we know about this man and how his term might impact Australia?

Xi Jinping has been Vice President since 2007 and, at 59 years old, is one of the youngest members of the Communist Party leadership. His father was a revolutionary war hero who went on to become Vice President. However, in 1962 his father had a falling out with Mao and was jailed during the Cultural Revolution. Xi himself was sent to do hard labour in the countryside and ended up living in a cave, sleeping on bricks, and fending off fleas. Xi openly admits to outsiders that the Cultural Revolution was ‘a failure for the nation’—unusual candour from a Chinese leader.

Rather than becoming embittered towards the Communist Party that jailed his father and exiled him to live in a cave, Xi made several attempts to join the Communist Party and was finally accepted in 1974. When Xi became Party Vice President he was careful not to ruffle the feathers of any of his colleagues and he remained clear of political scandals. Xi’s rise was marked by a keen support for the private sector and a rational business sense that allowed him to build the economies of Fujian and Zhejiang provinces.

So, what might Xi’s rule over the second most powerful country in the world mean for Australia? It’s very difficult to know how China might change under Xi because, like Hu before him, Xi has kept silent on a number of issues. However, there are some things we can infer from his past conduct as well as from some off-the-cuff political statements.

Despite calls for Xi to make sweeping political change, his allegiance to the Communist Party suggests he won’t be making any drastic domestic changes. Plus, Xi himself has told us that he will be just as assertive in regional territorial disputes: in September, Xi told ASEAN leaders that he would safeguard China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and, in the same month, issued a sternwarning to Japan over the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku islands, telling it to ‘rein in its behaviour’.

We also have some sense of Xi’s feelings towards the West and towards the US pivot to Asia. In 2009, while in Mexico, Xi lashed out at the West (possibly in response to US and UK criticism over China’s human rights record) by saying that China had already made a contribution to the financial crisis by feeding all of its citizens and that ‘there are a few foreigners…who have nothing better to do than try to point fingers at our country’. However, on the US pivot to Asia, Xi has projected a softer stance, stating in September this year that diplomatic visits between the US and China were advancing state-to-state and military-to-military relations. Whatever Xi’s true feelings towards the US pivot, the US and China share many common security interests in the region, many of which will require cooperation rather than competition to resolve.

And what does Xi think about Australia? During a trip to Australia in 2010 Xi called it a trustworthy partner and said that Australia–China relations were of great importance. But, that was in 2010. Although Xi has said nothing publicly, he is probably highly critical of the decision to station US Marines in Darwin as are other Chinese leaders. However, Xi no doubt recognises the paramount importance of the Australia–China trade relationship and Xi’s strong background in fostering economic growth is likely to serve us well.

Xi’s personal style (markedly different from Hu) may also bode well for Australia. By many accounts, Xi seems more approachable as well as more confident than his soon-to-be predecessor. Kevin Rudd has praised Xi, calling him ‘the man for the times’, with ‘vast experience’. ANU Professor Richard Rigby characterises Xi as ‘a man who’s comfortable in his own skin—he’s a princeling but one who has come up the hard way’. Professor Rigby adds, ‘Xi of course would never hesitate to crack down if and when he thought necessary, but neither does he pick fights unnecessarily, and prefers to work with people rather than against them, as long as that’s possible’.

So, should Australia welcome the rise of Xi Jinping or will he give Chinese policies a sharper tone that will work contrary to our interests? Reflecting on his formative years sleeping in a cave and labouring in the country, Xi said, ‘Knives are sharpened on the stone. People are refined through hardship. Whenever I later encountered trouble, I’d just think of how hard it had been to get things done back then and nothing would then seem difficult.’ While Xi will have foreign policy challenges to overcome as President, at this point in China’s development he’ll find more hardships at home. If Xi’s attention is focused on domestic issues he’ll have less opportunity to assert Chinese dominance in the region, which is good news for Australia. Whatever leader Xi turns out to be, China’s domestic problems will certainly give him more opportunity to hone his character.

Hayley Channer is an analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Image courtesy of Flickr user Secretary of Defense.